Arts In LA

Meet the Artists

Theater News

What’s on S.T.A.G.E.?

The LA theater community continues to rally around AIDS Project LA.

by Jonas Schwartz

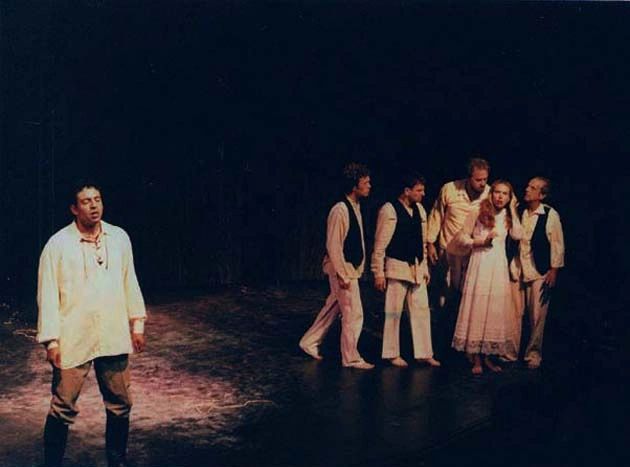

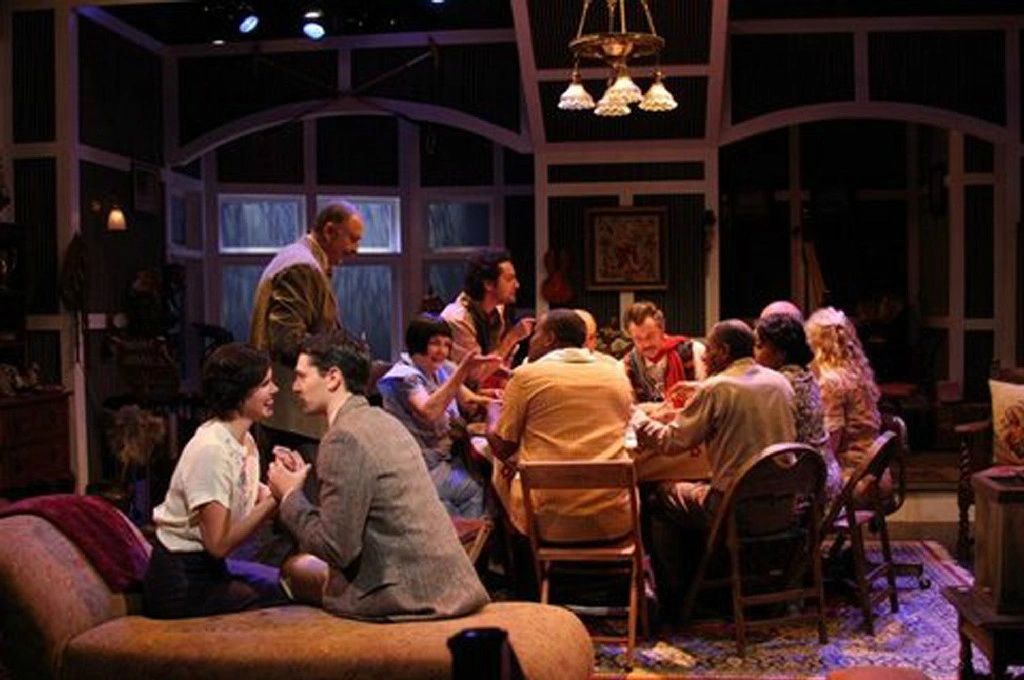

S.T.A.G.E. stars onstage for 2011’s gala event

The Los Angeles theater community has not forgotten the battle against AIDS, and it continues to take the fight to the S.T.A.G.E. The Southland Theatre Artists Goodwill Event (S.T.A.G.E.) has partnered with AIDS Project Los Angeles (APLA) for the last 32 years to raise money for AIDS education and prevention by presenting musical delights from some of Los Angeles’s biggest theater talents. This year’s concert, Sondheim No. 5, will take place at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts for a matinee and an evening performance June 18.

Once again, big names and theater stalwarts will share the stage. This year’s lineup includes the Emmy-, Grammy-, Oscar-, and Tony-winning Rita Moreno, along with Tony winner Marissa Winokur (Hairspray) and original Dreamgirl Loretta Divine. The cast of more than 25 welcomes relative newcomers such as Julie Garnyé among veterans of the concert such as Carole Cook and Mary Jo Catlett. Director David Galligan has helmed the project since the days before a name for the deadly disease had even been coined.

Galligan says the S.T.A.G.E. production is “a celebration of life” where often the songs reflect the struggles caused by the illness. “This year, we have Branden James singing ‘Every Day a Little Death’ [from Stephen Sondheim’s A Little Night Music] with his partner James Clark accompanying him on cello. Branden is HIV positive, with his partner negative. Another song, Company’s ‘Being Alive’ will comment on the temporary relief from AIDS due to the cocktail. We will also pay tribute to S.T.A.G.E. family members who have passed away from AIDS with a memoriam crawl.”

Galligan says the S.T.A.G.E. production is “a celebration of life” where often the songs reflect the struggles caused by the illness. “This year, we have Branden James singing ‘Every Day a Little Death’ [from Stephen Sondheim’s A Little Night Music] with his partner James Clark accompanying him on cello. Branden is HIV positive, with his partner negative. Another song, Company’s ‘Being Alive’ will comment on the temporary relief from AIDS due to the cocktail. We will also pay tribute to S.T.A.G.E. family members who have passed away from AIDS with a memoriam crawl.”

Cook will perform ‘I’m Still Here’ from Follies. “If you were singing this song in Follies, it would be the character [Carlotta] singing the song about herself, but here, it’s Carole Cook singing those words,” Cook says. “It’s what I’ve been through. I’ve had a long career. At my age I can really mean that song. You have to be older to sing that song. Women with glorious voices sing it, but you have to have a lot of road to sing that from the heart.”

Back in 1984, the creators put the show together flying by the seat of their pants. Cook, who has performed in 30 of the past productions, remembers those early days. “We had a guy in the chorus of 42nd Street who had this mystery illness. At the time, there was no help for people who were ill. A lot of us pulled together money every month, and there were enough of us…to pay for [the sufferers’] rent, food, and care for their animals,” Cook says.

Michael Kearns and the late James Carroll Pickett decided to put on a benefit and enlisted their friend Galligan. Tickets were $10, and people donated food cans. Cook recalls, “We had no help at all. We did all of it. We’d clean the toilets, sweep the floors, and chip in and get a coffee pot for the backstage. We had no makeup people, no hair people. It was like an old Judy Garland/Mickey Rooney movie. ‘Gee, kids, why don’t we fix it up here and put on a show.’”

“In that first year, we honored Leonard Bernstein’s music, so I had Donna McKechnie doing ‘Cool; from West Side Story,” Galligan recalls. “The stage at Variety Arts downtown had a loading dock door, on a chain pulley, that opened into a parking lot. Behind was a skyline of LA. I had the idea that everyone in the lot should turn on their cars’ headlights. So we had Donna McKechnie, flooded from behind by these lights, and downtown LA in the background. It was fantastic and didn’t cost a cent. The audience went nuts during those days, over the moon. I don’t think the theater community had a benefit that was comparable. Much of the audience was weeping throughout the show because they had lost so many friends.”

Over the years, the group found more and more supporters and volunteers. Recalls Cook, “My hairdresser from 42nd Street, Russell Smith, came to one of the early shows. He saw all these women with flat hair and said they were walking beauty violations. So he would come in and do everyone’s hair. Then he got the makeup people to contribute.”

“In the early days, [musical director] Ron Abel and I set the show up at the Embassy Theater downtown,” Galligan says. “The show ran 5 and a half hours long. Intermission came at 11:30 at night. And yet it was a gorgeous show. [Betty] Buckley came out at 1 in the morning to sing her song. MCA did a recording of the show but they weren’t even able to put in half of the songs.”

These days, lighting designers, set designers, choreographers, stage crew, musical directors, and stage management donating their time and resources. Even restaurants, including West Hollywood’s Café D’Etoile, come to feed the cast and crew each year.

“The theater community is so much closer than the film community,” Galligan says. “Because the rehearsal process is so long for a play or musical, everyone remains tight. So when you put out a call, they answer immediately.”

“S.T.A.G.E. is special, because it’s homegrown,” Cook notes.

This is S.T.A.G.E.’s first time at the Wallis, which houses fewer seats than past venues. To make up for the fewer seats, the producers have added a matinee. “It’s such a beautiful theater,” says Galligan. “In some ways, it will be a smaller show, but in other ways it will be larger— elegant, but a little bit raunchy.”

Each year, the program highlights a famous composer, such as Jerry Herman, or a musical theme, like last year’s To Broadway From Hollywood...With Love. This year is the fifth time S.T.A.G.E. has chosen the works of Sondheim.

New Generations, Same Dread Disease

“Music has changed so much with the advent of American Idol and The Voice,” says Galligan. “Audiences for S.T.A.G.E. used to come to see their favorite tunes of Jule Styne and Gershwin. But now there’s an apathy from younger audiences toward the classics. They don’t even know who many of the [golden era] composers are.” But Galligan says he believes that Sondheim’s music is different, that it speaks to multiple generations. “[Sondheim’s music] breaks my heart. He understands so many emotions that we feel in a lifetime. I can apply many of the emotions evoked from the songs to the AIDS epidemic.”

Cook adds, “The saddest thing, through the years, we began to lose part of our cast. That really brought it home. But now [the country has gotten] complacent [about AIDS]. The younger generation is cavalier about it because of the cocktail—a word that annoys me because it minimizes it and makes it sound so easy. For people with AIDS, it’s not easy. I wish the younger generation would be more cognizant of the effects of AIDS.”

“I feel sometimes the audience is dwindling,” Galligan observes. “A lot of people feel that there’s a cure for AIDS, and there’s not. The cocktail is temporary relief for AIDS but not a cure. They’ve moved on, and AIDS is no longer the disease of the month. With the testing and the clinics, APLA is a wonderful organization.”

The income from tickets to the event remains essential, supporting all APLA programs. According to APLA’s chief advancement officer Charles Robbins, APLA helps more than 14,000 men and women with services annually—including HIV prevention; health education; free and low-cost medical, dental, and mental health services; food pantries; housing support services; nonmedical case management; benefits counseling; community forums; and nutrition education.

One thing is clear: The danger of AIDS is not a thing of the past. As Robbins notes, “HIV rates are increasing in young black and Latino men who have sex with men; nearly 60,000 people in LA County live with HIV today; and one-eighth of the people in the US who are infected with HIV don’t know it. There is a malaise, which is why our prevention programs are so important.”

As long as APLA’s services are needed, S.T.A.G.E. expects to entertain and still raise important funds for the organization. “We’re still in there fighting the good fight and hopefully bringing some joy,” Cook says. “A few laughs never hurt, darling.”

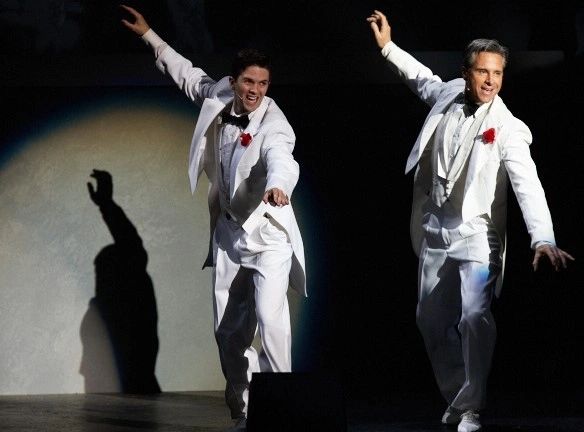

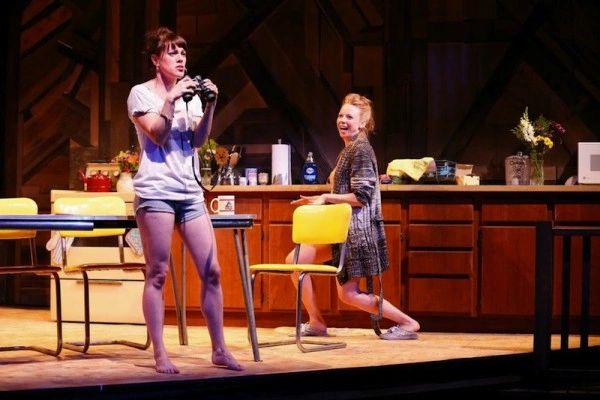

Carole Cook in the 2014 event

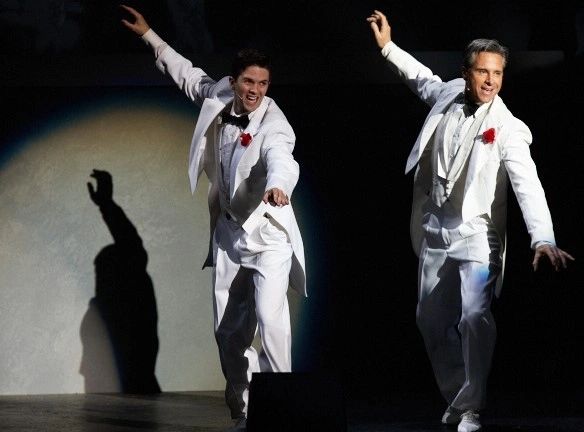

Jeffrey Scott Parsons and David Engel in a 2014 tribute to Fred Astaire

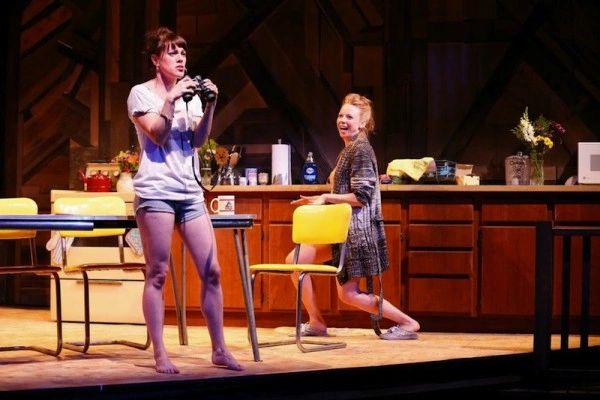

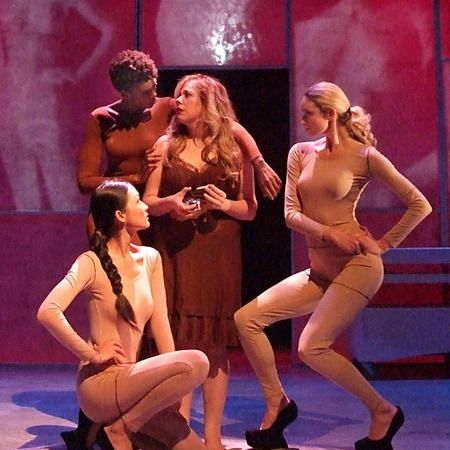

Terri White, Kathy Garrick, Mary Jo Catlett, and Marsha Kramer, 2013.

Photos by Chris Kane

What’s on S.T.A.G.E.?

The LA theater community continues to rally around AIDS Project LA.

by Jonas Schwartz

S.T.A.G.E. stars onstage for 2011’s gala event

Photo courtesy S.T.A.G.E.

The Los Angeles theater community has not forgotten the battle against AIDS, and it continues to take the fight to the S.T.A.G.E. The Southland Theatre Artists Goodwill Event (S.T.A.G.E.) has partnered with AIDS Project Los Angeles (APLA) for the last 32 years to raise money for AIDS education and prevention by presenting musical delights from some of Los Angeles’s biggest theater talents. This year’s concert, Sondheim No. 5, will take place at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts for a matinee and an evening performance June 18.

Once again, big names and theater stalwarts will share the stage. This year’s lineup includes the Emmy-, Grammy-, Oscar-, and Tony-winning Rita Moreno, along with Tony winner Marissa Winokur (Hairspray) and original Dreamgirl Loretta Divine. The cast of more than 25 welcomes relative newcomers such as Julie Garnyé among veterans of the concert such as Carole Cook and Mary Jo Catlett. Director David Galligan has helmed the project since the days before a name for the deadly disease had even been coined.

Galligan says the S.T.A.G.E. production is “a celebration of life” where often the songs reflect the struggles caused by the illness. “This year, we have Branden James singing ‘Every Day a Little Death’ [from Stephen Sondheim’s A Little Night Music] with his partner James Clark accompanying him on cello. Branden is HIV positive, with his partner negative. Another song, Company’s ‘Being Alive’ will comment on the temporary relief from AIDS due to the cocktail. We will also pay tribute to S.T.A.G.E. family members who have passed away from AIDS with a memoriam crawl.”

Galligan says the S.T.A.G.E. production is “a celebration of life” where often the songs reflect the struggles caused by the illness. “This year, we have Branden James singing ‘Every Day a Little Death’ [from Stephen Sondheim’s A Little Night Music] with his partner James Clark accompanying him on cello. Branden is HIV positive, with his partner negative. Another song, Company’s ‘Being Alive’ will comment on the temporary relief from AIDS due to the cocktail. We will also pay tribute to S.T.A.G.E. family members who have passed away from AIDS with a memoriam crawl.”Cook will perform ‘I’m Still Here’ from Follies. “If you were singing this song in Follies, it would be the character [Carlotta] singing the song about herself, but here, it’s Carole Cook singing those words,” Cook says. “It’s what I’ve been through. I’ve had a long career. At my age I can really mean that song. You have to be older to sing that song. Women with glorious voices sing it, but you have to have a lot of road to sing that from the heart.”

Back in 1984, the creators put the show together flying by the seat of their pants. Cook, who has performed in 30 of the past productions, remembers those early days. “We had a guy in the chorus of 42nd Street who had this mystery illness. At the time, there was no help for people who were ill. A lot of us pulled together money every month, and there were enough of us…to pay for [the sufferers’] rent, food, and care for their animals,” Cook says.

Michael Kearns and the late James Carroll Pickett decided to put on a benefit and enlisted their friend Galligan. Tickets were $10, and people donated food cans. Cook recalls, “We had no help at all. We did all of it. We’d clean the toilets, sweep the floors, and chip in and get a coffee pot for the backstage. We had no makeup people, no hair people. It was like an old Judy Garland/Mickey Rooney movie. ‘Gee, kids, why don’t we fix it up here and put on a show.’”

“In that first year, we honored Leonard Bernstein’s music, so I had Donna McKechnie doing ‘Cool; from West Side Story,” Galligan recalls. “The stage at Variety Arts downtown had a loading dock door, on a chain pulley, that opened into a parking lot. Behind was a skyline of LA. I had the idea that everyone in the lot should turn on their cars’ headlights. So we had Donna McKechnie, flooded from behind by these lights, and downtown LA in the background. It was fantastic and didn’t cost a cent. The audience went nuts during those days, over the moon. I don’t think the theater community had a benefit that was comparable. Much of the audience was weeping throughout the show because they had lost so many friends.”

Over the years, the group found more and more supporters and volunteers. Recalls Cook, “My hairdresser from 42nd Street, Russell Smith, came to one of the early shows. He saw all these women with flat hair and said they were walking beauty violations. So he would come in and do everyone’s hair. Then he got the makeup people to contribute.”

“In the early days, [musical director] Ron Abel and I set the show up at the Embassy Theater downtown,” Galligan says. “The show ran 5 and a half hours long. Intermission came at 11:30 at night. And yet it was a gorgeous show. [Betty] Buckley came out at 1 in the morning to sing her song. MCA did a recording of the show but they weren’t even able to put in half of the songs.”

These days, lighting designers, set designers, choreographers, stage crew, musical directors, and stage management donating their time and resources. Even restaurants, including West Hollywood’s Café D’Etoile, come to feed the cast and crew each year.

“The theater community is so much closer than the film community,” Galligan says. “Because the rehearsal process is so long for a play or musical, everyone remains tight. So when you put out a call, they answer immediately.”

“S.T.A.G.E. is special, because it’s homegrown,” Cook notes.

This is S.T.A.G.E.’s first time at the Wallis, which houses fewer seats than past venues. To make up for the fewer seats, the producers have added a matinee. “It’s such a beautiful theater,” says Galligan. “In some ways, it will be a smaller show, but in other ways it will be larger— elegant, but a little bit raunchy.”

Each year, the program highlights a famous composer, such as Jerry Herman, or a musical theme, like last year’s To Broadway From Hollywood...With Love. This year is the fifth time S.T.A.G.E. has chosen the works of Sondheim.

New Generations, Same Dread Disease

“Music has changed so much with the advent of American Idol and The Voice,” says Galligan. “Audiences for S.T.A.G.E. used to come to see their favorite tunes of Jule Styne and Gershwin. But now there’s an apathy from younger audiences toward the classics. They don’t even know who many of the [golden era] composers are.” But Galligan says he believes that Sondheim’s music is different, that it speaks to multiple generations. “[Sondheim’s music] breaks my heart. He understands so many emotions that we feel in a lifetime. I can apply many of the emotions evoked from the songs to the AIDS epidemic.”

Cook adds, “The saddest thing, through the years, we began to lose part of our cast. That really brought it home. But now [the country has gotten] complacent [about AIDS]. The younger generation is cavalier about it because of the cocktail—a word that annoys me because it minimizes it and makes it sound so easy. For people with AIDS, it’s not easy. I wish the younger generation would be more cognizant of the effects of AIDS.”

“I feel sometimes the audience is dwindling,” Galligan observes. “A lot of people feel that there’s a cure for AIDS, and there’s not. The cocktail is temporary relief for AIDS but not a cure. They’ve moved on, and AIDS is no longer the disease of the month. With the testing and the clinics, APLA is a wonderful organization.”

The income from tickets to the event remains essential, supporting all APLA programs. According to APLA’s chief advancement officer Charles Robbins, APLA helps more than 14,000 men and women with services annually—including HIV prevention; health education; free and low-cost medical, dental, and mental health services; food pantries; housing support services; nonmedical case management; benefits counseling; community forums; and nutrition education.

One thing is clear: The danger of AIDS is not a thing of the past. As Robbins notes, “HIV rates are increasing in young black and Latino men who have sex with men; nearly 60,000 people in LA County live with HIV today; and one-eighth of the people in the US who are infected with HIV don’t know it. There is a malaise, which is why our prevention programs are so important.”

As long as APLA’s services are needed, S.T.A.G.E. expects to entertain and still raise important funds for the organization. “We’re still in there fighting the good fight and hopefully bringing some joy,” Cook says. “A few laughs never hurt, darling.”

June 5, 2016

Carole Cook in the 2014 event

Jeffrey Scott Parsons and David Engel in a 2014 tribute to Fred Astaire

Terri White, Kathy Garrick, Mary Jo Catlett, and Marsha Kramer, 2013.

Photos by Chris Kane

Interview

The West of the Story

New Yorkers bring Rattlestick Playwrights Theater to LA, hoping to sprout roots.

By Bob Verini

Maxwell Hamilton and Seth Numrich in Rattlestick Playwrights Theater’s 2013 production of Slipping

Ever wonder what our friends back East really think about the Los Angeles theater scene? You may not be surprised by the report of theater artist Daniel Talbott, who makes his home in the Big Apple and isn’t one to mince words.

“When I’d tell people I was coming here to do a play, some would say, ‘That’s awesome,’ but others would say, ‘Why the fuck would you ever want to do a play there?”

Currently directing his third LA production in three years, Talbott is in the vanguard of an ambitious new bicoastal theatrical venture that could shake up our town in truly exciting ways.

Currently directing his third LA production in three years, Talbott is in the vanguard of an ambitious new bicoastal theatrical venture that could shake up our town in truly exciting ways.

The undertaking is called Rattlestick West, and it makes its debut with Talbott’s workshop of What Happened When, now running at North Hollywood’s The Sherry Theater through Oct. 25. Under the leadership of artistic director David Van Asselt, the company hopes to stake its claim as a major producer of new work here by some of the hottest playwrights anywhere.

It’s no idle notion, since over 21 years Rattlestick Playwrights Theater has fostered work by the likes of David Adjmi, Martin Moran, Lucy Thurber, Adam Rapp, Annie Baker, and Jonathan Tolins, whose Buyer & Cellar was a Rattlestick hit back East before it took the Mark Taper Forum by storm. As established as Van Asselt is in Manhattan, he has had his eye on the left coast for a long time, Talbott reports.

A Rattlestick artistic associate, Talbott was formerly its literary manager until a plethora of TV and film projects forced him to step away. He notes, “In L.A. you have a very supportive, über-talented, loving community where you can just do a play and it doesn’t suddenly bring in the colossus of The New York Times, that public expectation that can put so much pressure on a writer. Here you just put it in a room”—The Sherry boasts about 30 seats—“and it’s OK to fail. Whereas in New York, if you fail hugely, the play never gets done again.”

Rattlestick’s brand began to be familiar to Southern California audiences with Talbott’s 2013 production of his Slipping, starring Seth Numrich at the now-deceased Lillian Theater, which was followed this spring by Charlotte Miller’s Thieves at the El Portal.

Even more prominently, the company’s 2014 co-production with and at The Theater @ Boston Court, Sheila Callaghan’s Everything You Touch, walked off with five LA Drama Critics Circle Awards including the Ted Schmitt Award for local world premiere, and transferred to New York City earlier this year to continued acclaim.

“We still value our relationship with Boston Court and hope to keep working with them.” But Van Asselt, says Talbott, “has been looking for a home of our own, a small little black-boxy place that could be very developmental, taking the emphasis off expensive production and focusing on new-play development.”

The Sherry, on Magnolia in NoHo, just fit the bill, and by the playwright’s description, What Happened When should serve as an apt tone-setter.

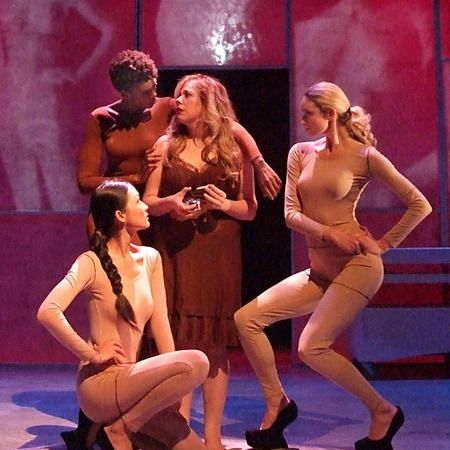

Kirsten Vangsness, at center, in Everything You Touch, Theatre @ Boston Court 2014

“Not to imply that I’m anywhere near these playwrights, but I’d say it’s a little [Caryl] Churchill, [Harold] Pinteresque with some hyperrealism…. It started as a scene I wrote about the sexual abuse of two brothers by their biological father, and how men don’t talk about certain things and what that can lead to.” Over time he added two scenes to his two-hander, and he will be bringing it in in a taut 65 minutes.

“It’s a claustrophobic, intense, simplistic play with a lot of stakes underneath it, hopefully. And I’m doing it with two of my favorite young actors: Will Pullen and Jimi Stanton.” Pullen recently won raves in the New York premiere of Simon Stephens’s Punk Rock, while Stanton, whom Talbott met at an Equity open call, has done four shows with him since.

“It’s changing every day: We rehearse, then I rewrite, and the next day we try something new. And we’re laughing a lot and telling a lot of jokes,” says Talbott. A workshop production, What Happened When will not be available for review, and Talbott expects script revisions to continue throughout the eight-performance run.

After Oct. 25, whither Rattlestick West? Talbott reports that Van Asselt will depend on producers Scott Haze and Lukas Behnken to keep operations going at The Sherry, but “he’ll be coming back out here every month or so.” Tantalizing hints are dropped of works in progress or under consideration.

Michael Urie in 2014 production of Buyer & Cellar at Mark Taper Forum

“There’s a Suzanne Vega/Cyndi Lauper musical about homeless youth. A Don Juan modern kind of YouTube thing with James Franco. And a new Lucy Thurber play, hyperrealistic, about poverty in rural Massachusetts. Also, I’m working on a new play for Rattlestick set in a Jack-in-the-Box, about someone using sexual power to get this kid to steal for him. It’s pretty dark.”

By his own admission, Talbott doesn’t get much sleep. With several TV pilots and other commissions in the hopper, he continues to run his own Manhattan-based company, Rising Phoenix Rep, with wife Addie and colleagues Sam Soule, Denis Butkus, and Julie Kline. “I started it in 1999 as a small theater along the lines of the Magic and Eureka companies in the Bay Area: a small place for working professionals with an open-door policy as members for life.”

Yet as established and happy as Talbott is as a New York–based artist and family man, Los Angeles keeps beckoning. “It’s very heart-driven out here,” he says. “You’re not doing it because you want to win an Obie or an amazing Times review, and there’s none of the glitz and glamour motivating it.” He reels off a laundry list of companies whose work he’s seen on his trips here—including Circle X, Rogue Machine, Celebration, and IAMA, whose production of Micah Schraft’s A Dog’s House he admired earlier this year.

“My experience with people here, Simon Levy [of Fountain Theatre] and Deaf West, all tells me they’re just doing it because they fucking love theater. You all do it 100 million percent because you love it. And I love that.”

The West of the Story

New Yorkers bring Rattlestick Playwrights Theater to LA, hoping to sprout roots.

By Bob Verini

Maxwell Hamilton and Seth Numrich in Rattlestick Playwrights Theater’s 2013 production of Slipping

Photo by Ryan Miller/Capture Imaging

Ever wonder what our friends back East really think about the Los Angeles theater scene? You may not be surprised by the report of theater artist Daniel Talbott, who makes his home in the Big Apple and isn’t one to mince words.

“When I’d tell people I was coming here to do a play, some would say, ‘That’s awesome,’ but others would say, ‘Why the fuck would you ever want to do a play there?”

Currently directing his third LA production in three years, Talbott is in the vanguard of an ambitious new bicoastal theatrical venture that could shake up our town in truly exciting ways.

Currently directing his third LA production in three years, Talbott is in the vanguard of an ambitious new bicoastal theatrical venture that could shake up our town in truly exciting ways.The undertaking is called Rattlestick West, and it makes its debut with Talbott’s workshop of What Happened When, now running at North Hollywood’s The Sherry Theater through Oct. 25. Under the leadership of artistic director David Van Asselt, the company hopes to stake its claim as a major producer of new work here by some of the hottest playwrights anywhere.

It’s no idle notion, since over 21 years Rattlestick Playwrights Theater has fostered work by the likes of David Adjmi, Martin Moran, Lucy Thurber, Adam Rapp, Annie Baker, and Jonathan Tolins, whose Buyer & Cellar was a Rattlestick hit back East before it took the Mark Taper Forum by storm. As established as Van Asselt is in Manhattan, he has had his eye on the left coast for a long time, Talbott reports.

A Rattlestick artistic associate, Talbott was formerly its literary manager until a plethora of TV and film projects forced him to step away. He notes, “In L.A. you have a very supportive, über-talented, loving community where you can just do a play and it doesn’t suddenly bring in the colossus of The New York Times, that public expectation that can put so much pressure on a writer. Here you just put it in a room”—The Sherry boasts about 30 seats—“and it’s OK to fail. Whereas in New York, if you fail hugely, the play never gets done again.”

Sarah Shaefer and Samantha Soule in 2015 production of Thieves

Photo by Ryan Miller/Capture ImagingRattlestick’s brand began to be familiar to Southern California audiences with Talbott’s 2013 production of his Slipping, starring Seth Numrich at the now-deceased Lillian Theater, which was followed this spring by Charlotte Miller’s Thieves at the El Portal.

Even more prominently, the company’s 2014 co-production with and at The Theater @ Boston Court, Sheila Callaghan’s Everything You Touch, walked off with five LA Drama Critics Circle Awards including the Ted Schmitt Award for local world premiere, and transferred to New York City earlier this year to continued acclaim.

“We still value our relationship with Boston Court and hope to keep working with them.” But Van Asselt, says Talbott, “has been looking for a home of our own, a small little black-boxy place that could be very developmental, taking the emphasis off expensive production and focusing on new-play development.”

The Sherry, on Magnolia in NoHo, just fit the bill, and by the playwright’s description, What Happened When should serve as an apt tone-setter.

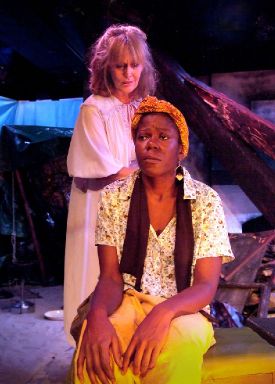

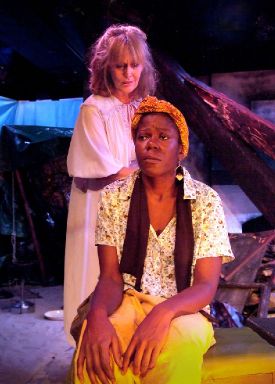

Kirsten Vangsness, at center, in Everything You Touch, Theatre @ Boston Court 2014

Photo by Ed Krieger

“Not to imply that I’m anywhere near these playwrights, but I’d say it’s a little [Caryl] Churchill, [Harold] Pinteresque with some hyperrealism…. It started as a scene I wrote about the sexual abuse of two brothers by their biological father, and how men don’t talk about certain things and what that can lead to.” Over time he added two scenes to his two-hander, and he will be bringing it in in a taut 65 minutes.

“It’s a claustrophobic, intense, simplistic play with a lot of stakes underneath it, hopefully. And I’m doing it with two of my favorite young actors: Will Pullen and Jimi Stanton.” Pullen recently won raves in the New York premiere of Simon Stephens’s Punk Rock, while Stanton, whom Talbott met at an Equity open call, has done four shows with him since.

“It’s changing every day: We rehearse, then I rewrite, and the next day we try something new. And we’re laughing a lot and telling a lot of jokes,” says Talbott. A workshop production, What Happened When will not be available for review, and Talbott expects script revisions to continue throughout the eight-performance run.

After Oct. 25, whither Rattlestick West? Talbott reports that Van Asselt will depend on producers Scott Haze and Lukas Behnken to keep operations going at The Sherry, but “he’ll be coming back out here every month or so.” Tantalizing hints are dropped of works in progress or under consideration.

Michael Urie in 2014 production of Buyer & Cellar at Mark Taper Forum

“There’s a Suzanne Vega/Cyndi Lauper musical about homeless youth. A Don Juan modern kind of YouTube thing with James Franco. And a new Lucy Thurber play, hyperrealistic, about poverty in rural Massachusetts. Also, I’m working on a new play for Rattlestick set in a Jack-in-the-Box, about someone using sexual power to get this kid to steal for him. It’s pretty dark.”

By his own admission, Talbott doesn’t get much sleep. With several TV pilots and other commissions in the hopper, he continues to run his own Manhattan-based company, Rising Phoenix Rep, with wife Addie and colleagues Sam Soule, Denis Butkus, and Julie Kline. “I started it in 1999 as a small theater along the lines of the Magic and Eureka companies in the Bay Area: a small place for working professionals with an open-door policy as members for life.”

Yet as established and happy as Talbott is as a New York–based artist and family man, Los Angeles keeps beckoning. “It’s very heart-driven out here,” he says. “You’re not doing it because you want to win an Obie or an amazing Times review, and there’s none of the glitz and glamour motivating it.” He reels off a laundry list of companies whose work he’s seen on his trips here—including Circle X, Rogue Machine, Celebration, and IAMA, whose production of Micah Schraft’s A Dog’s House he admired earlier this year.

“My experience with people here, Simon Levy [of Fountain Theatre] and Deaf West, all tells me they’re just doing it because they fucking love theater. You all do it 100 million percent because you love it. And I love that.”

October 15, 2015

Interview

The Odyssey of a Lifetime

Ron Sossi recalls the road he traveled to become a fixture on the LA theater scene.

By Bob Verini

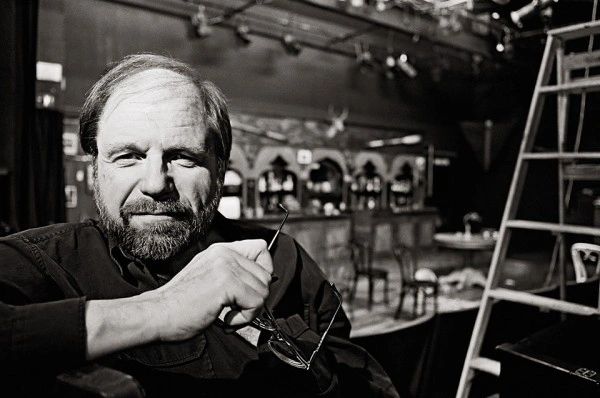

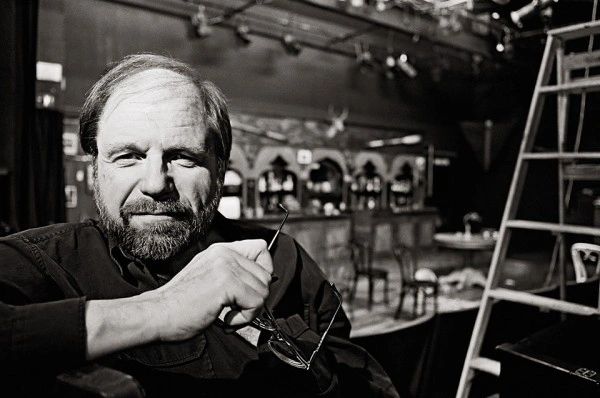

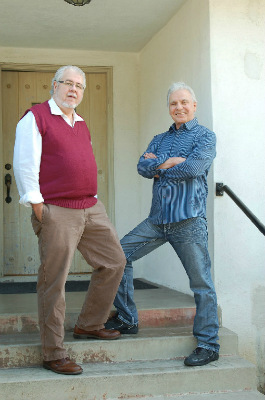

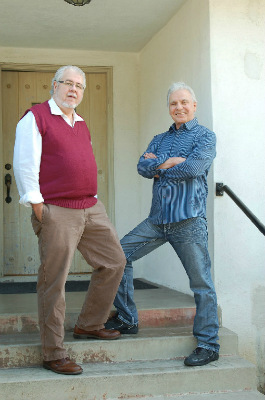

Ron Sossi, founder and artistic director of Odyssey Theatre

Bob Verini interviewed Sossi by telephone in June 2015, in the midst of Odyssey Theater’s 46th season.

Bob Verini: How did you come to form the theater, and how does it operate as an organization today?

Ron Sossi: Ironically, it was originally formed out of frustration. We make plans but life happens anyway. I found myself now 46 years later running a theater, which isn’t necessarily what I would have planned. I came out to Hollywood, to Los Angeles, to go to UCLA graduate film school from the University of Michigan. After I got out of film school, I wanted a job. In those days, young directors—[directing] is what I was interested in—were not very much in vogue. Unless you were at least 30 years old, nobody took you seriously. It’s kind of the opposite today. It was very difficult to get any kind of opportunity to direct, particularly when it was the era of film and not videotape, which is so much cheaper now.

I tried to get any kind of job I could. I finally went in as an assistant to a producer on a series. I later became an executive at a network and then after that an executive at a studio, really riding herd on a number of TV series I was assigned to. And that was kind of interesting for a while. I did it for about six years. About midway through that, I really got frustrated because I wasn’t getting any closer to directing. Out of that frustration, I started a theater. I started it with my ex-wife’s acting coach. We began this theater in North Hollywood, starting with classes and with the intention to produce. And as that captured me more and more, as I became more and more interested in what was going on in the world of theater—I was very influenced by the Polish director Jerzy Grotowski and also by the work of Joe Chaikin in New York. As that focused me more and more, finally I bid goodbye to the industry and decided to spend full time doing theater.

We actually began our first productions at a little storefront in Hollywood—the seedy end of Hollywood Boulevard between Western and Vermont—at an 81-seat house that had been a spiritualist church. After we left, it became a porno theater. We started in ’69 and we were there through ’73. In ’73 we found a larger building in West LA, a warehouse, where we moved and created one theater, ultimately creating three theaters in that space. That was at Santa Monica [Boulevard] and Bundy. We were there for 14 years. Then the building got sold out from under us, and we were kind of paid off to leave early, to allow the landlord to break the lease. We used that money to convert the building that we eventually found, that we’re in now, at Sepulveda Boulevard near Olympic. The theater began as a very tight, small membership company. Everybody paid, as I remember, $25 a month dues. We all had to do everything. I think we had 12, 14 members in the company. The idea was to continue working with a very tight ensemble.

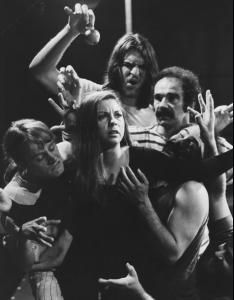

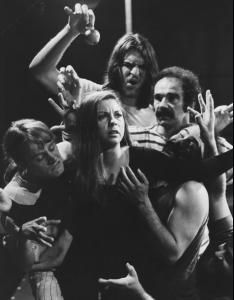

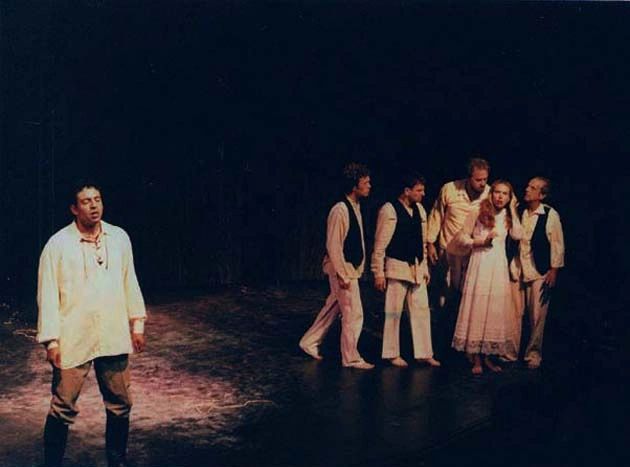

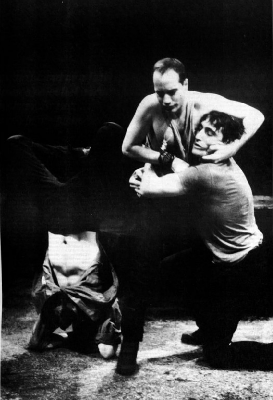

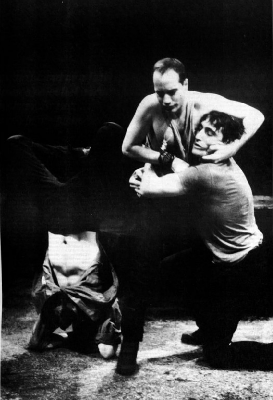

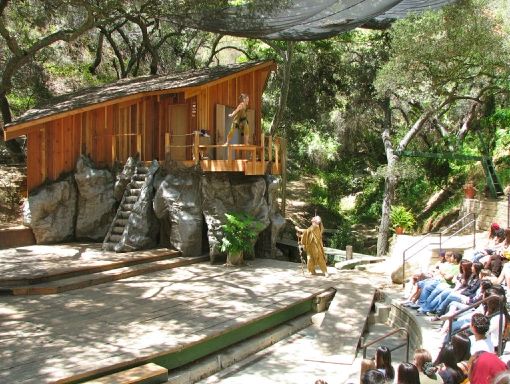

The Serpent [pictured] was our early show, as was The Threepenny Opera. Threepenny Opera ran for 14 months, which was a very long run. People would call and say, “Okay, we saw Threepenny Opera, we loved it, when is your next show?” We would say, “We’re still doing Threepenny Opera.” So it was very hard to build an audience. We were just doing one show at a time over a long period of time. The Serpent ran for eight months. So we decided we needed to have a larger company and be able to produce more-frequently. That’s why we went to the second building, where we could have three spaces. If we had a long run, fine. That long run could continue, but at the same time we could open other projects with other members of the company.

The Serpent [pictured] was our early show, as was The Threepenny Opera. Threepenny Opera ran for 14 months, which was a very long run. People would call and say, “Okay, we saw Threepenny Opera, we loved it, when is your next show?” We would say, “We’re still doing Threepenny Opera.” So it was very hard to build an audience. We were just doing one show at a time over a long period of time. The Serpent ran for eight months. So we decided we needed to have a larger company and be able to produce more-frequently. That’s why we went to the second building, where we could have three spaces. If we had a long run, fine. That long run could continue, but at the same time we could open other projects with other members of the company.

That set us on the season path, where we would do a season of six to eight plays. That continues today. We didn’t want to fall into the mold of just doing a play and rehearsing for a short period and running it as was the norm in the regional theaters. We wanted to be able to develop new work and develop projects that were long term.

The Faust Projekt

So a number of years into this process, we formed a group called the Koan, which is still the Odyssey Theatre but is a sort of unit within the Odyssey of Koan members. That group was designed to pursue my interest, which was metaphysical subjects. And often do it over a long period, so we would develop works. We did such things as The Faust Projekt, our own version of Faust. We did an evening of Kafka. We did an evening that explored the Buddhism, Buddha’s Big Night. And so forth. That group continues to exist. It does maybe one show every year and a half.

[The Odyssey] functions as a season. We do six shows a year now. We’ve been through kind of every structure you could imagine. We were a dues-paying membership company, where actors had to do work hours, as happens in most membership companies in LA. But very early on, I was determined to get us out of that mold because we were limited to 99 seats and couldn’t pay actors any reasonable amount of money. We at least wanted to get to the place where they weren’t paying dues and ultimately where they weren’t doing work around the theater other than being actors. That was a big priority. We tried to professionalize the staff, a small underpaid staff, which we have today. Still, the actors do not pay dues. They don’t have to do anything around the theater.

Verini: That’s the progression every company hopes for, but you’ve taken it beyond that to, in my opinion essential, an resource and crown jewel, and I think it’s partly because of everything you’ve talked about and also because the Odyssey is during the year also home to co-productions and guest productions and outside rentals. Doesn’t that help with the variety, as well?

Sossi: Of course. It’s also not only a desirable thing to get that variety in there, but it’s also a necessity, because with the small staff we have and the company we have, to produce more than six shows a year would really be burnout time. We’re always at the edge of burnout anyway, but six is plenty. To keep three theaters filled, you can’t do that with six productions a year. So we do invite other companies in as co-productions, sometimes. At other times, we just rent the theater, and we rent it at a modes rate—all we want to do is cover our overhead.

And then we bring in companies from Europe, at times when that’s possible. That’s always a financial burden that makes it impossible most of the time. But sometimes we’ll find foreign companies that are either funded by their governments or they’re coming here to perform maybe in the University of California system where their costs are already to a large extent paid for. So we’ve had German companies, Polish companies, British companies, Finnish companies, South American, and so on, through the years. We really like to do that. Being in America, it’s very difficult for theater people, theater audiences and theater artists, to be exposed to what’s happening, the state of the art, in world theater. If you live in France, you buy a train ticket and you hop across to England or to Germany or wherever. You can see what’s going on. Here, being isolated by oceans, that becomes extremely difficult. So anytime we can have an opportunity to bring in a company, we do so. And then co-productions with local companies, with New York companies, and then rentals.

Verini: To those who haven’t been to the Odyssey, what’s the vibe like on a given night or weekend afternoon? What will somebody who encounters the Odyssey for the first time confront?

Sossi: It’s usually pretty exciting because we have one central lobby that serves all the theaters. It also has an outdoor patio where people can go out and sit at little tables and have a drink or sandwich. Because there are often three productions playing at the same time, not always, but often, you have an audience of up to 300 people milling around, waiting for the shows to begin and kind of being exposed to the audiences of the other two theaters, so there’s a lot of talk about, “Did you see that?” or “Oh, you’ve got to see that.”

Now we’re doing a production of Oedipus called Oedipus Machina. And somebody might have come to see the play we just closed, called Sunset Baby, which is a contemporary, naturalistic, African-American play. Well someone might have come to see that and seen the poster or seen the reviews or talked to audience members who were going in to see Oedipus. Maybe they never would have thought of coming to see Oedipus. But because they’re in the lobby, and because there’s a buzz, and there’s sort of cross-fertilization, they may very well end up doing that.

Martin Rayner and Joshua Wolf Coleman in the current production of Oedipus Machina

Verini: You directed Oedipus. How do you go about deciding what you will direct, and what led you to this project in particular?

Sossi: Well, people often say, “Why do you pick what you pick?” I pick what we do for the Odyssey as a whole, not just myself as a director, with a certain mind to a kind of variety. It usually comes out to a certain rule of thumb where we do one-third classically oriented material, hopefully that we will treat with some kind of innovative new approach; one-third of new plays, either brand-new or maybe the second production of a play; and thirdly, the best stuff that seems to be coming out of the international theater world. We might do a very interesting British play that was just performed in Britain, and so on.

In terms of my own, personal tastes, I can’t tell you. I tend toward things that are either very theatrically exciting in terms of form or style, and/or very exciting content-wise. Sometimes it’s only one, sometimes it’s a very exciting naturalistic play with a subject matter that’s rather explosive. The form in that case might be very conventional. But the subject matter is extremely interesting.

Verini: This new project sounds like it touches all those bases. It’s got some of the most important existential questions, and I think you found a pretty exciting metaphor for it.

Sossi: I always wanted to do Oedipus, and I can’t tell you why except that it does, as you say, address very metaphysical questions: the ideas of fate and destiny, and what are we doing here, are we acting of our free will or is there something else controlling us, either on the outside as the Greeks believe or our unconscious urges. The play has always fascinated me. I found a marvelous new translation, by Ellen McLaughlin, and also had a notion that because of what the Greeks believed—that we are controlled by our destiny or our fate—I started working with the metaphor of a giant machine onstage, that would sort of grind the events of the play out and reveal the characters. The characters would sort of be spurted out of the machine as they were needed to conduct this sort of free-range fate-oriented spectacle.

That machine idea was the central metaphor. As the piece developed, I also became very interested in a couple of other ideas. One is the idea that Oedipus was actually the story of Akhenaten, the pharaoh of Egypt. There’s a lot of evidence that seems to point to that. That was kind of fascinating to me. I didn’t want to do it as an Egyptian setting. That was a little bit on the nose. But I did start to want to do it as a more abstract ancient culture, not saying it’s Greece, not saying it’s a place of white stairways and white togas, but rather some kind of ancient undescribable civilization.

And then the other idea that came into it is my fascination with this idea of ancient aliens—that perhaps a number of our cultures have been seeded way back by interplanetary visitors. There’s a lot of fascinating stuff about that. And so the show is not Star Trek, and it doesn’t suggest a science-fiction approach, but it has some subtle influences that suggest that the story is happening amidst a royal family that is a descendent of these kinds of beings. People of the land are really more endemic to Earth. So you have a chorus that is earthbound, and you have a royal family that has the seeds of perhaps some other heritage. And that became a fascinating idea, and that’s what we pursued. And it helps illuminate the play, I think, in many, many ways. So that was fascinating both as content and as form, as I was talking about.

We have a piece coming up, a classical piece, which will be rather traditional in form; although, Bart DeLorenzo is directing it, so it won’t be totally traditional. It should be quite exciting. It’s a comedy, The False Servant, by Marivaux. And then we have the inimitable Steven Berkoff of Britain coming in to direct O’Neill’s The Hairy Ape, one of my favorite classic Americana plays. We’re doing a revival of Awake and Sing, by Clifford Odets. It’s kind of a very mixed bag. We’ve always tried to be very eclectic.

We really like the idea that our audience doesn’t quite know what to expect from us, that they can come one week and see a heavy naturalistic piece about explosive stuff, like [The] Chicago Conspiracy [Trial], or Tracers that was originally developed by Vietnam vets who were members of our theater. And the next week, they can come and see a Brecht piece. And the next week they can come see a silly satiric musical. And the next week, they can come and see a heavy metaphysical piece that has a lot of style and innovation to it. The idea of keeping the audience on the edge and letting theater be an event has always appealed to me, so it’s not just another play. You don’t know what’s going to happen. Of course that’s hard to maintain sometimes, over six productions a year. But that’s what we try to do.

The Odyssey of a Lifetime

Ron Sossi recalls the road he traveled to become a fixture on the LA theater scene.

By Bob Verini

Ron Sossi, founder and artistic director of Odyssey Theatre

Photo courtesy Odyssey Theatre

Ask theatergoers in Los Angeles to name one of the best places to see a production, and most will name Odyssey Theatre among their favorites. Ron Sossi founded it in the late 1960s, and throughout the years he has remained its artistic director. Today, the Odyssey occupies an iconic blue building on Sepulveda Boulevard in West Los Angeles, housing three 99-Seat theaters, where theatergoers can see classics, world premieres, musicals, solo shows—anything, Sossi says, that is “very exciting” and “extremely interesting.”Bob Verini interviewed Sossi by telephone in June 2015, in the midst of Odyssey Theater’s 46th season.

Bob Verini: How did you come to form the theater, and how does it operate as an organization today?

Ron Sossi: Ironically, it was originally formed out of frustration. We make plans but life happens anyway. I found myself now 46 years later running a theater, which isn’t necessarily what I would have planned. I came out to Hollywood, to Los Angeles, to go to UCLA graduate film school from the University of Michigan. After I got out of film school, I wanted a job. In those days, young directors—[directing] is what I was interested in—were not very much in vogue. Unless you were at least 30 years old, nobody took you seriously. It’s kind of the opposite today. It was very difficult to get any kind of opportunity to direct, particularly when it was the era of film and not videotape, which is so much cheaper now.

I tried to get any kind of job I could. I finally went in as an assistant to a producer on a series. I later became an executive at a network and then after that an executive at a studio, really riding herd on a number of TV series I was assigned to. And that was kind of interesting for a while. I did it for about six years. About midway through that, I really got frustrated because I wasn’t getting any closer to directing. Out of that frustration, I started a theater. I started it with my ex-wife’s acting coach. We began this theater in North Hollywood, starting with classes and with the intention to produce. And as that captured me more and more, as I became more and more interested in what was going on in the world of theater—I was very influenced by the Polish director Jerzy Grotowski and also by the work of Joe Chaikin in New York. As that focused me more and more, finally I bid goodbye to the industry and decided to spend full time doing theater.

We actually began our first productions at a little storefront in Hollywood—the seedy end of Hollywood Boulevard between Western and Vermont—at an 81-seat house that had been a spiritualist church. After we left, it became a porno theater. We started in ’69 and we were there through ’73. In ’73 we found a larger building in West LA, a warehouse, where we moved and created one theater, ultimately creating three theaters in that space. That was at Santa Monica [Boulevard] and Bundy. We were there for 14 years. Then the building got sold out from under us, and we were kind of paid off to leave early, to allow the landlord to break the lease. We used that money to convert the building that we eventually found, that we’re in now, at Sepulveda Boulevard near Olympic. The theater began as a very tight, small membership company. Everybody paid, as I remember, $25 a month dues. We all had to do everything. I think we had 12, 14 members in the company. The idea was to continue working with a very tight ensemble.

The Serpent [pictured] was our early show, as was The Threepenny Opera. Threepenny Opera ran for 14 months, which was a very long run. People would call and say, “Okay, we saw Threepenny Opera, we loved it, when is your next show?” We would say, “We’re still doing Threepenny Opera.” So it was very hard to build an audience. We were just doing one show at a time over a long period of time. The Serpent ran for eight months. So we decided we needed to have a larger company and be able to produce more-frequently. That’s why we went to the second building, where we could have three spaces. If we had a long run, fine. That long run could continue, but at the same time we could open other projects with other members of the company.

The Serpent [pictured] was our early show, as was The Threepenny Opera. Threepenny Opera ran for 14 months, which was a very long run. People would call and say, “Okay, we saw Threepenny Opera, we loved it, when is your next show?” We would say, “We’re still doing Threepenny Opera.” So it was very hard to build an audience. We were just doing one show at a time over a long period of time. The Serpent ran for eight months. So we decided we needed to have a larger company and be able to produce more-frequently. That’s why we went to the second building, where we could have three spaces. If we had a long run, fine. That long run could continue, but at the same time we could open other projects with other members of the company.That set us on the season path, where we would do a season of six to eight plays. That continues today. We didn’t want to fall into the mold of just doing a play and rehearsing for a short period and running it as was the norm in the regional theaters. We wanted to be able to develop new work and develop projects that were long term.

The Faust Projekt

Photo by Yevgenia Nayberg (costume designer)

So a number of years into this process, we formed a group called the Koan, which is still the Odyssey Theatre but is a sort of unit within the Odyssey of Koan members. That group was designed to pursue my interest, which was metaphysical subjects. And often do it over a long period, so we would develop works. We did such things as The Faust Projekt, our own version of Faust. We did an evening of Kafka. We did an evening that explored the Buddhism, Buddha’s Big Night. And so forth. That group continues to exist. It does maybe one show every year and a half.

[The Odyssey] functions as a season. We do six shows a year now. We’ve been through kind of every structure you could imagine. We were a dues-paying membership company, where actors had to do work hours, as happens in most membership companies in LA. But very early on, I was determined to get us out of that mold because we were limited to 99 seats and couldn’t pay actors any reasonable amount of money. We at least wanted to get to the place where they weren’t paying dues and ultimately where they weren’t doing work around the theater other than being actors. That was a big priority. We tried to professionalize the staff, a small underpaid staff, which we have today. Still, the actors do not pay dues. They don’t have to do anything around the theater.

Verini: That’s the progression every company hopes for, but you’ve taken it beyond that to, in my opinion essential, an resource and crown jewel, and I think it’s partly because of everything you’ve talked about and also because the Odyssey is during the year also home to co-productions and guest productions and outside rentals. Doesn’t that help with the variety, as well?

Sossi: Of course. It’s also not only a desirable thing to get that variety in there, but it’s also a necessity, because with the small staff we have and the company we have, to produce more than six shows a year would really be burnout time. We’re always at the edge of burnout anyway, but six is plenty. To keep three theaters filled, you can’t do that with six productions a year. So we do invite other companies in as co-productions, sometimes. At other times, we just rent the theater, and we rent it at a modes rate—all we want to do is cover our overhead.

And then we bring in companies from Europe, at times when that’s possible. That’s always a financial burden that makes it impossible most of the time. But sometimes we’ll find foreign companies that are either funded by their governments or they’re coming here to perform maybe in the University of California system where their costs are already to a large extent paid for. So we’ve had German companies, Polish companies, British companies, Finnish companies, South American, and so on, through the years. We really like to do that. Being in America, it’s very difficult for theater people, theater audiences and theater artists, to be exposed to what’s happening, the state of the art, in world theater. If you live in France, you buy a train ticket and you hop across to England or to Germany or wherever. You can see what’s going on. Here, being isolated by oceans, that becomes extremely difficult. So anytime we can have an opportunity to bring in a company, we do so. And then co-productions with local companies, with New York companies, and then rentals.

Verini: To those who haven’t been to the Odyssey, what’s the vibe like on a given night or weekend afternoon? What will somebody who encounters the Odyssey for the first time confront?

Sossi: It’s usually pretty exciting because we have one central lobby that serves all the theaters. It also has an outdoor patio where people can go out and sit at little tables and have a drink or sandwich. Because there are often three productions playing at the same time, not always, but often, you have an audience of up to 300 people milling around, waiting for the shows to begin and kind of being exposed to the audiences of the other two theaters, so there’s a lot of talk about, “Did you see that?” or “Oh, you’ve got to see that.”

Now we’re doing a production of Oedipus called Oedipus Machina. And somebody might have come to see the play we just closed, called Sunset Baby, which is a contemporary, naturalistic, African-American play. Well someone might have come to see that and seen the poster or seen the reviews or talked to audience members who were going in to see Oedipus. Maybe they never would have thought of coming to see Oedipus. But because they’re in the lobby, and because there’s a buzz, and there’s sort of cross-fertilization, they may very well end up doing that.

Martin Rayner and Joshua Wolf Coleman in the current production of Oedipus Machina

Photo by Enci Box

Verini: You directed Oedipus. How do you go about deciding what you will direct, and what led you to this project in particular?

Sossi: Well, people often say, “Why do you pick what you pick?” I pick what we do for the Odyssey as a whole, not just myself as a director, with a certain mind to a kind of variety. It usually comes out to a certain rule of thumb where we do one-third classically oriented material, hopefully that we will treat with some kind of innovative new approach; one-third of new plays, either brand-new or maybe the second production of a play; and thirdly, the best stuff that seems to be coming out of the international theater world. We might do a very interesting British play that was just performed in Britain, and so on.

In terms of my own, personal tastes, I can’t tell you. I tend toward things that are either very theatrically exciting in terms of form or style, and/or very exciting content-wise. Sometimes it’s only one, sometimes it’s a very exciting naturalistic play with a subject matter that’s rather explosive. The form in that case might be very conventional. But the subject matter is extremely interesting.

Verini: This new project sounds like it touches all those bases. It’s got some of the most important existential questions, and I think you found a pretty exciting metaphor for it.

Sossi: I always wanted to do Oedipus, and I can’t tell you why except that it does, as you say, address very metaphysical questions: the ideas of fate and destiny, and what are we doing here, are we acting of our free will or is there something else controlling us, either on the outside as the Greeks believe or our unconscious urges. The play has always fascinated me. I found a marvelous new translation, by Ellen McLaughlin, and also had a notion that because of what the Greeks believed—that we are controlled by our destiny or our fate—I started working with the metaphor of a giant machine onstage, that would sort of grind the events of the play out and reveal the characters. The characters would sort of be spurted out of the machine as they were needed to conduct this sort of free-range fate-oriented spectacle.

That machine idea was the central metaphor. As the piece developed, I also became very interested in a couple of other ideas. One is the idea that Oedipus was actually the story of Akhenaten, the pharaoh of Egypt. There’s a lot of evidence that seems to point to that. That was kind of fascinating to me. I didn’t want to do it as an Egyptian setting. That was a little bit on the nose. But I did start to want to do it as a more abstract ancient culture, not saying it’s Greece, not saying it’s a place of white stairways and white togas, but rather some kind of ancient undescribable civilization.

And then the other idea that came into it is my fascination with this idea of ancient aliens—that perhaps a number of our cultures have been seeded way back by interplanetary visitors. There’s a lot of fascinating stuff about that. And so the show is not Star Trek, and it doesn’t suggest a science-fiction approach, but it has some subtle influences that suggest that the story is happening amidst a royal family that is a descendent of these kinds of beings. People of the land are really more endemic to Earth. So you have a chorus that is earthbound, and you have a royal family that has the seeds of perhaps some other heritage. And that became a fascinating idea, and that’s what we pursued. And it helps illuminate the play, I think, in many, many ways. So that was fascinating both as content and as form, as I was talking about.

We have a piece coming up, a classical piece, which will be rather traditional in form; although, Bart DeLorenzo is directing it, so it won’t be totally traditional. It should be quite exciting. It’s a comedy, The False Servant, by Marivaux. And then we have the inimitable Steven Berkoff of Britain coming in to direct O’Neill’s The Hairy Ape, one of my favorite classic Americana plays. We’re doing a revival of Awake and Sing, by Clifford Odets. It’s kind of a very mixed bag. We’ve always tried to be very eclectic.

We really like the idea that our audience doesn’t quite know what to expect from us, that they can come one week and see a heavy naturalistic piece about explosive stuff, like [The] Chicago Conspiracy [Trial], or Tracers that was originally developed by Vietnam vets who were members of our theater. And the next week, they can come and see a Brecht piece. And the next week they can come see a silly satiric musical. And the next week, they can come and see a heavy metaphysical piece that has a lot of style and innovation to it. The idea of keeping the audience on the edge and letting theater be an event has always appealed to me, so it’s not just another play. You don’t know what’s going to happen. Of course that’s hard to maintain sometimes, over six productions a year. But that’s what we try to do.

June 15, 2015

Knowing the Score

Songwriter Michael Patrick Walker explains a bit about putting the music in musical theater.

by Dany Margolies

Heidi Blickenstaff, Eric William Morris, Beth Leavel as Rhoda, Jon Patrick Walker, and Nicole Parker in Dog and Pony

Michael Patrick Walker lives in a time and place very different from that occupied by Cole Porter, but the career Walker chose for himself very much follows in those exalted footsteps. Walker is a songwriter, working in musical theater, responsible for the songs that make the whole world sing—or at least they currently make The Old Globe sing.

Co-creator of Altar Boyz in 2005, he later joined forces with Peter and the Starcatcher’s writer Rick Elice to create Dog and Pony, now in its world premiere run at San Diego’s Old Globe theater, directed by Roger Rees.

It’s romantic comedy about a successful screenwriting team. His marriage falters, she’s single, and of course the audience finds out if romance between the two is possible.

To find out more about the art and skill involved in being a musical-theater songwriter, we spoke with Walker by telephone on his day off from rehearsals for Dog and Pony.

As a child, did you write songs?

Michael Patrick Walker: I did. I don’t know if I ever wrote them down. When I was 4, I approached my mother and said, “I want to take piano lessons,” out of the blue. They rented a piano for two weeks, figuring that’s how long I would stay interested. They still have that piano—a rent-to-own thing. I don’t know what sparked that request and what it is that clicked. I studied piano and would make up little songs.

Michael Patrick Walker: I did. I don’t know if I ever wrote them down. When I was 4, I approached my mother and said, “I want to take piano lessons,” out of the blue. They rented a piano for two weeks, figuring that’s how long I would stay interested. They still have that piano—a rent-to-own thing. I don’t know what sparked that request and what it is that clicked. I studied piano and would make up little songs.

Eventually you went to Carnegie Mellon University. Did you study music there?

Walker: I did not. I had been studying as a pianist privately all that time, and my piano teacher was encouraging me, but at the time, if you were going to study music as a pianist, you pretty much were studying to be a classical concert pianist. Which is a wonderful, lovely thing, but you really have to love to go into that for a living. It’s a very difficult thing to do, and it’s a very lonely existence. It wasn’t something I felt strongly enough about. And by then, I had been doing so much theater; that was where the music had taken me. That being said, at Carnegie Mellon, it’s a very conservatory atmosphere, so there really wasn’t a way to be an undergraduate. You could be an actor, a singer, an instrumentalist, but there wasn’t a cross-discipline major that allowed that. I also considered being doctor and a scientist. So I ended up going to Carnegie Mellon for mathematics and computer science, and doing so much theater and music work that I was often being pulled in six different directions at the same time.

Had you become involved in theater in high school?

Walker: Yes, and again it was one of those accidental situations. I played for all the choirs. I was in junior high, called middle school in Pennsylvania. High school had recently revived their musical theater program. They weren’t to the point yet where they were doing a full orchestra with shows, so they were doing maybe piano or two pianos. When I was in eighth grade, they were going to do The Sound of Music. There’s a wonderful two-piano version of the show that was licensed. They had an adult music director and needed somebody to play the other piano part. Knowing I had this skill, the choir director said, “There’s this guy, he’s been playing for me for several years.” That was my first exposure: playing second piano for The Sound of Music. It opened my eyes, a way to take music I’d known for years, but also to tell a story with music, lyrics, book scenes. Sitting there, playing the show, understanding, was the beginning of that. That method of using my musical skills and talents to tell a story.

Those are the two words I was going to ask you about: talent and skill.

Walker: You can make this analogy with actors as well. You can get a robot that could play the piano, you can have a player piano, where you can program the exact time each note should be pressed, and how long each key should be held, and you will hear a song. And that, in a way, is skill. You have to have that. If you just have that, it’s the notes, and that’s about all it is. The talent comes in how you interpret it, what feeling and emotions you put into those notes when you play them. And it’s not enough just to have that, either. To do anything in the arts, you need both—to play, to perform, to write, even to do something people think is not a creative endeavor, but they’re wrong, which is being on the crew: You have to have understanding of the timing of when the curtain needs to go out. The director can say, but if you aren’t thinking what the storytelling is, the curtain jerks out. There are people who have one and not the other—they’re very skilled, but they don’t have that emotional connection, and people who have a very strong emotional connection but not the skill to fully realize it. That’s why it’s so exciting when you see a performer or a show, and you see both come together.

How do you get started on a composition, whether a full musical or a single song?

Walker: I wish I knew. That’s something I still discover on case-by-case, show-by-show, song-by-song, sometimes measure-by measure basis. As far as a show goes, if you look at the big picture too soon, you’re going to crawl back under the covers and curl up into a ball. It’s too daunting. So you have to have that, “What’s the story, the general idea?” That’s where I have to start. What kind of story are we trying to tell? Who are the characters? What are the plot points? Then you can go, “Okay, boy’s going to meet girl, girl’s going to break up with boy, then they’re going to get back together.” Then you can look at it and say, “I have an idea for what she could do when she breaks up,” and maybe that’s the first kernel that you start to realize, and you start to play around with the melody, musical feel, lyrics. In some cases, when the show is done, that initial song will have been rewritten or cut. But that was the in, the foot in the door to the whole story. It’s rarely the first song in the show. You find something and go, “What’s speaking to me, what’s calling my name?” Then for a specific song, I mostly write music and lyrics together. On rare occasions, I have collaborated on a song, but because I write them together, I don’t know how it all happens. Very often they come at the same time in my brain, with the piano, sort of riffing on things. And then once you get a little piece of it, it forms. “Okay, what’s the journey of this song? Where are we starting, where are we ending?” Then there’s the actual work: scratching things out, rewriting. And, hopefully, in the case of musicals, a couple of years later you have a show.

How do you avoid “borrowing” from existing melodies? Is there a way of checking?

Walker: Knock wood, it hasn’t happened to me frequently. There are only 12 notes from C to C, so in theory all of the combinations have been done. But you can listen to almost anything and find three intervals, and think, “That’s something I’ve heard.” Some if it is, you can’t worry about that too much. Of course, if you find yourself writing something and realizing it’s eight measures of another song, that’s a problem. That hasn’t happened to me very often. It’s just a matter of there’s so much involved in a melody. It is the notes and their intervolic relationships, but it’s also the rhythm, feel, vibe, lyric. There will be little things that sound like something else every now and again, but that doesn’t tend to be a problem unless they’re exactly the same thing. If you’re going to write something that sounds exactly like “Comedy Tonight” for eight bars, that’s a problem, and you have to make sure that doesn’t happen. But the good thing is, because you’re writing and creating, you might hum something and go, “Oh yeah, that’s a great tune. That’s because it was written 20 years ago.” Once in a blue moon I have found myself questioning when I’ve written something, and four weeks later, when I go back to it, I realize it’s so familiar to me, and I realize it’s because I wrote it four weeks ago.

Do you do your own orchestrations?

Walker: Not typically. I did one album called “Out of Context,” all but one track of that. I am what I would consider a competent orchestrator—I can do it. When at all possible, I will have someone who is much more skilled and that is one of the things they do. For Dog and Pony, the amazingly talented, Tony Award–winning Larry Hochman is doing the orchestrations. He was the first person I called, when we knew we were doing the show. He had orchestrated one or two things of mine in the past. To my great good fortune, he was available and excited about doing it, and he’s here in San Diego as we get ready for the first preview.

Are you told in advance you’re writing it for a certain number of instruments or combination of instruments? Or doesn’t it matter to you?

Walker: When I’m writing, I hear whatever sound I’m going to hear. You can’t think about that because it would box you in too much. That being said, orchestration is a very collaborative form. Whatever the orchestrator does, we go through it. “Here maybe instead of soprano saxophone, it should be a tenor.” There’s a back-and-forth collaboration. The actual instrumentation is a point of discussion and negotiation. For Dog and Pony, we’d never done the show before, so this is the very first time it’s been orchestrated. This version is very true to the score. It’s also a world premiere, so it’s not a 20-piece orchestra. I don’t know that this show would ever call for a 20-piece orchestra. It’s not that kind of show. It’s one of the more business clashes over creative issues that happens. Usually you come up with something that works.

So this is not a 20-piece orchestra because it’s only five-actor musical?

Walker: It’s a five-actor musical, and you can do a five-actor musical and have a gigantic orchestra. There’s no rule that says that’s not the case. This is more a matter of style. That being said, if you’re doing I Do, I Do, and you’ve got two people on the stage, and that’s it, if you had the London Philharmonic playing the score, it’s a little bit of a mismatch. But, there’s a lot of room in there. You could do a small show with piano only. You could also do a nine-person orchestra. It all becomes a matter of what’s the right fit and feel. Here at the Globe, we’re doing the show in the round. That’s an additional set of circumstances. With five actors on the stage, if the first time they sang, you heard 65 strings, it would be a little confusing. In the end, it comes down to the score. If this score were an old-style Rodgers and Hammerstein score, where you want to hear that soaring sound, that’s what we’d go for. It’s not that. Nor is it a rock-pop thing. It’s in that middle ground: contemporary musical theater, pop influences, and traditional influences. And that lands you with an orchestral sound. You have a drum kit, but you also have a ballad with flute that you wouldn’t necessarily get in, like, Rent.

How have you first met your collaborators? How did you meet Larry, for example?

Walker: I wrote a piece that is part of the Radio City Christmas Spectacular a number of years back. The music director said to me, “I don’t know who would orchestrate it. Do you have any thoughts? Somebody who might be good with this style?” And both the music director and I said Larry Hochman would be good. There are not that many orchestrators working in musical theater. So you go to a show and you hear people’s work. As a composer, I’ll take a look and see the instruments they put in and notice, “That’s really clever,” and “They really support the storytelling with their instrument choice.” So I’ve been a fan of his for a number of years. So when he did a song I wrote for the Christmas Spectacular, I got to meet him there. He did a fantastic job and really got what I was going for. The blanket job of an orchestrator, I think, is to take the intention of the composer and make it even better. You want to keep going in that same direction, and add the colors, and add the lines of different instruments that build on the original song if someone just plays it on the piano. Larry does that brilliantly. He gets inside what the character’s doing on stage in this number, and that affects his instrument choice. I won’t give anything away about Dog and Pony, but there’s a moment in the show that is a difficult moment for a character, and he’s using a piccolo, as opposed to a flute, which has a similar but a warmer sound. We’re used to hearing a piccolo at the top of John Philip Sousa marches. Here it’s used in a flute register and has a very cold sound, whereas a flute is warmer and happier. I don’t think anyone in the audience is going to think, “Aha, the piccolo made me feel that way.” But they’re affected by the instruments they hear in every song.

How did you get picked for Dog and Pony? Did you know Rick Elice before this?

Walker: Dog and Pony is one of those sadly unique situations. It’s not based on anything. It’s not a producer-thrust project. It’s something Rick and I came up with and began writing on our own, without knowing anything other than it was a story we were excited about and interested in telling. Later on, The Old Globe read it and was interested in producing it, to our great fortune.

But the actual way we first met: There was a time when Rick and I shared the same agent, and I had just seen Peter and the Starcatcher at New York Theatre Workshop before it moved to Broadway. I loved it. At the same time, there was a horrible movie, which I will not name, that I remembered vaguely from years ago. And I thought, “It was not a great movie but might actually adapt well into a musical.” My theory on adapting movies is that there’s nothing inherently wrong with it, but you should do it if there’s a reason. My benchmark on that is Little Shop of Horrors. So I remembered this movie that I won’t name, and I thought, “Rick has the exact right things.” I asked to meet with him, and again to my good fortune he was like, okay. We had coffee. We watched the movie. For about the first 10 minutes, we were looking at each other, and we realized the movie was much worse than I remembered it, and neither of us was much interested in making it into a musical. So the DVD went back in my bag, and we sat and talked for three hours about what kinds of stories and themes and characters and music was interesting to both of us. That conversation led to the very beginnings of what became Dog and Pony. It was a very fortunate and kind of accidental way we got into writing it.

But the actual way we first met: There was a time when Rick and I shared the same agent, and I had just seen Peter and the Starcatcher at New York Theatre Workshop before it moved to Broadway. I loved it. At the same time, there was a horrible movie, which I will not name, that I remembered vaguely from years ago. And I thought, “It was not a great movie but might actually adapt well into a musical.” My theory on adapting movies is that there’s nothing inherently wrong with it, but you should do it if there’s a reason. My benchmark on that is Little Shop of Horrors. So I remembered this movie that I won’t name, and I thought, “Rick has the exact right things.” I asked to meet with him, and again to my good fortune he was like, okay. We had coffee. We watched the movie. For about the first 10 minutes, we were looking at each other, and we realized the movie was much worse than I remembered it, and neither of us was much interested in making it into a musical. So the DVD went back in my bag, and we sat and talked for three hours about what kinds of stories and themes and characters and music was interesting to both of us. That conversation led to the very beginnings of what became Dog and Pony. It was a very fortunate and kind of accidental way we got into writing it.

We spent about two years working on the basic draft of the show, both of us going off to do other projects and taking a little break and coming back. When we had it to a point where it was ready to be seen, Barry Edelstein—the artistic director for the season that was just ending at The Old Globe—read it and was immediately interested in doing it. Again, to my surprise and joy, they literally said, “We want to do it.” They didn’t say “Let’s do a reading, let’s develop it.”

You did a reading in the fall. Did you ask for it?

Walker: It was sort of mutual. It had already been announced that we were doing the show for sure, but one of first things we said to them was, “That’s fantastic, but we’d literally sit in his living room and read the parts to each other.” You can only learn so much doing that. You need actors. You need to be able to sit back and see what works and what doesn’t. They were perfectly happy and onboard, but the Globe and we were like, we should do a reading in New York because that’s the opportunity to put it on its feet at music stands and go, “This character we need to fix, we need a new song here, this plot point doesn’t really work.”