Arts In LA

Arts In NY archives 2012–2015

(these shows are closed)

(these shows are closed)

China Doll

Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre

Reviewed by David Sheward

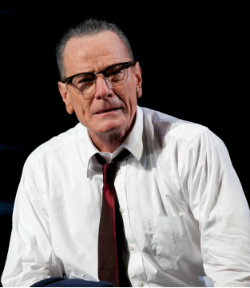

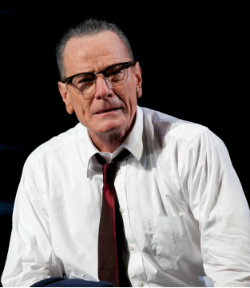

“I’m too old for the game,” moans Al Pacino as Mickey Ross, the billionaire wheeler-dealer at the center of David Mamet’s China Doll. Pacino could be speaking for himself and the playwright as well as the character. This latest work from the one-time master of the blistering, testosterone-fueled style of American drama is flabby (meandering monologues) and undeveloped (sketchy storyline). The actor is delivering a faint suggestion of the brash Pacino schtick. It’s like watching an early rehearsal of a first draft. One can only feel pity for director Pam MacKinnon who has previously shot new life into Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and A Delicate Balance. Her imprint is barely discernible as the pacing is slow and the plot confused.

The title is confusing as well. The china doll could mean Mickey’s girlfriend Frankie whom he frequently refers to as needing his protection. She, along with almost everyone connected with Mickey, is offstage at the other end of a Bluetooth connection. For most of the play, Pacino delivers one-sided conversations except for brief dialogues with Ross’s bland assistant Carson (Christopher Denham does the best he can with this shadowy role.)

From what we can piece together, the about-to-retire Ross has purchased a new airplane and had it flown to Canada, with the British Frankie as sole passenger, in order to avoid American sales tax. But the pilot had to touch down in the US before moving on to Toronto, and Mickey is now on the hook for $5 million. The whole frame-up is engineered by New York’s young governor—perhaps modeled on Andrew Cuomo—whom Mickey blasts as a rich hypocrite. This predicament gives Mamet the cue to have Ross launch several rambling speeches about the corruption of public officials and how being ruthless in business and politics is the sole path to wealth. (Spoiler alert: Apparently Mickey gets his comeuppance, but it’s ambiguous.)

What is Mamet saying here? That all politicians are liars, all voters are fools, and the only way to get ahead is to lie, cheat, and steal? And that we should admire those cutthroats and pirates who have the honesty to recognize this and rob the rest of us blind? That’s a perfectly valid, if extremely cynical viewpoint, but Mamet fails to make it compelling, as he has in earlier works. To compound the script’s flaws, Pacino appears to be struggling with his lines at the performance attended (to be fair, it’s a gigantic undertaking). He spends too much of the show sprawled on the attractive sofa in Derek McLane’s cavernous penthouse setting, only occasionally rousing himself to the old Pacino intensity. Mickey may be exhausted, but the star shouldn’t be.

After the curtain fell and the obligatory standing ovation was delivered, I felt a bit like Pacino and Mamet were laughing at us. Like Mickey and the slick salesmen of Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross, they’ve taken advantage of the public’s gullibility and charged top dollar for shoddy goods.

Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre

Reviewed by David Sheward

“I’m too old for the game,” moans Al Pacino as Mickey Ross, the billionaire wheeler-dealer at the center of David Mamet’s China Doll. Pacino could be speaking for himself and the playwright as well as the character. This latest work from the one-time master of the blistering, testosterone-fueled style of American drama is flabby (meandering monologues) and undeveloped (sketchy storyline). The actor is delivering a faint suggestion of the brash Pacino schtick. It’s like watching an early rehearsal of a first draft. One can only feel pity for director Pam MacKinnon who has previously shot new life into Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and A Delicate Balance. Her imprint is barely discernible as the pacing is slow and the plot confused.

The title is confusing as well. The china doll could mean Mickey’s girlfriend Frankie whom he frequently refers to as needing his protection. She, along with almost everyone connected with Mickey, is offstage at the other end of a Bluetooth connection. For most of the play, Pacino delivers one-sided conversations except for brief dialogues with Ross’s bland assistant Carson (Christopher Denham does the best he can with this shadowy role.)

From what we can piece together, the about-to-retire Ross has purchased a new airplane and had it flown to Canada, with the British Frankie as sole passenger, in order to avoid American sales tax. But the pilot had to touch down in the US before moving on to Toronto, and Mickey is now on the hook for $5 million. The whole frame-up is engineered by New York’s young governor—perhaps modeled on Andrew Cuomo—whom Mickey blasts as a rich hypocrite. This predicament gives Mamet the cue to have Ross launch several rambling speeches about the corruption of public officials and how being ruthless in business and politics is the sole path to wealth. (Spoiler alert: Apparently Mickey gets his comeuppance, but it’s ambiguous.)

What is Mamet saying here? That all politicians are liars, all voters are fools, and the only way to get ahead is to lie, cheat, and steal? And that we should admire those cutthroats and pirates who have the honesty to recognize this and rob the rest of us blind? That’s a perfectly valid, if extremely cynical viewpoint, but Mamet fails to make it compelling, as he has in earlier works. To compound the script’s flaws, Pacino appears to be struggling with his lines at the performance attended (to be fair, it’s a gigantic undertaking). He spends too much of the show sprawled on the attractive sofa in Derek McLane’s cavernous penthouse setting, only occasionally rousing himself to the old Pacino intensity. Mickey may be exhausted, but the star shouldn’t be.

After the curtain fell and the obligatory standing ovation was delivered, I felt a bit like Pacino and Mamet were laughing at us. Like Mickey and the slick salesmen of Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross, they’ve taken advantage of the public’s gullibility and charged top dollar for shoddy goods.

December 13, 2015

Dada Woof Papa Hot

Lincoln Center Theater at the Mitzi Newhouse Theatre

Steve

The New Group at the Pershing Square Signature Center

Reviewed by David Sheward

Now that same-sex marriage is the law of the land and many gay men are leading “heteronormative” lives complete with children and mortgages, how will they adjust to the excruciating rigors of monogamy, parenthood, and not constantly going to bars? That’s the vital questions two new Off-Broadway plays are daringly asking (sarcasm intended.) Side note: There is a lesbian character in one of the plays, but she plays a supporting part and is not essential to the action.

Coincidentally Peter Parnell’s Dada Woof Papa Hot from Lincoln Center Theatre and Mark Gerrard’s Steve from The New Group opened within a few days of each other. Both shallowly portray a group of upper-middle-class gay friends, many of whom are unable to cope with long-term commitment and indulge in meaningless affairs. The acting, direction, and design are professional and precise in both cases, but the scripts wear thin long before their respective 90-minute running times click off. Dada focuses on parenthood and is a tad deeper than the jokier Steve, which overdoses on musical theater references and gimmicky supertitles. Both have moments of humor and pathos but are ultimately disappointing.

In Dada, Alan and Rob’s marriage seems perfect on the surface. They have a lovely apartment (John Lee Beatty created the gorgeous sliding sets), a sweet prekindergarten-age daughter named Nikki, and apparently successful careers as writer and therapist. But Alan is frustrated by a shortage of journalistic work and Nikki’s preference for Rob, her biological father. So he launches an affair with Jason, a much younger married gay dad with fidelity issues of his own.

The two daddies in Steve, Steven and Stephen—cute that they have almost the same name, huh?—face similar conflicts. Stephen compulsively trades sexually explicit texts with one of the couple’s best friends Brian, and Steven retaliates by sleeping with an attractive waiter named Esteban. Meanwhile, Brian and his partner Matt are having a live-in threesome with their trainer, also named Steven. Do you sense a pattern here? The nearly identical names bit is stretched too much like many of Gerrard’s other gags such as the endless quoting of show lyrics. Also in the mix is Carrie, the token lesbian of the group who is afflicted with cancer and may get a movie deal out of her blog. Steven, Matt, and Carrie met as singing wait staff in a Broadway restaurant and have abandoned their attempts at musical-comedy careers. The theme of crushed dreams and mourning for lost youth is an intriguing one, but Gerrard fails to develop it.

The playwrights have the worthy concept of showing that gay people can be just as screwed up as their straight counterparts when faced with the challenge of building a socially sanctioned life with one partner, but the protagonists of Dada and Steve are defined by their sexual impulses, and their psychological motivations are not sufficiently explored to get us to care about them. In Dada, Alan comes across as a whiny narcissist, and in Steve we get sketchy show fans. A good therapist would work wonders with these people. Since they can afford nannies, weekends on Fire Island, private schools, and fabulous NYC apartments, you’d think they would try one.

Despite the thinness of the material, directors Scott Ellis (Dada) and Cynthia Nixon (Steve) deliver polished, sparkling stagings, and the casts gamely try to infuse their roles with the subtext the authors fail to provide. In Dada, John Benjamin Hickey almost makes the kvetchy Alan bearable, and Tammy Blanchard illuminates her cameo part of a pushy actor with an attractive energy. The Steve crowd has more opportunity for fun including a preshow sing-along at a standup piano. As the main couple, Matt McGrath and Malcolm Gets search in vain for the lovers beneath the quips and the song lyrics. Ashlie Atkinson is more successful in defining the caustic Carrie, and the hilarious Mario Cantone at least gets to cut up as Matt.

Lincoln Center Theater at the Mitzi Newhouse Theatre

Steve

The New Group at the Pershing Square Signature Center

Reviewed by David Sheward

Now that same-sex marriage is the law of the land and many gay men are leading “heteronormative” lives complete with children and mortgages, how will they adjust to the excruciating rigors of monogamy, parenthood, and not constantly going to bars? That’s the vital questions two new Off-Broadway plays are daringly asking (sarcasm intended.) Side note: There is a lesbian character in one of the plays, but she plays a supporting part and is not essential to the action.

Coincidentally Peter Parnell’s Dada Woof Papa Hot from Lincoln Center Theatre and Mark Gerrard’s Steve from The New Group opened within a few days of each other. Both shallowly portray a group of upper-middle-class gay friends, many of whom are unable to cope with long-term commitment and indulge in meaningless affairs. The acting, direction, and design are professional and precise in both cases, but the scripts wear thin long before their respective 90-minute running times click off. Dada focuses on parenthood and is a tad deeper than the jokier Steve, which overdoses on musical theater references and gimmicky supertitles. Both have moments of humor and pathos but are ultimately disappointing.

In Dada, Alan and Rob’s marriage seems perfect on the surface. They have a lovely apartment (John Lee Beatty created the gorgeous sliding sets), a sweet prekindergarten-age daughter named Nikki, and apparently successful careers as writer and therapist. But Alan is frustrated by a shortage of journalistic work and Nikki’s preference for Rob, her biological father. So he launches an affair with Jason, a much younger married gay dad with fidelity issues of his own.

The two daddies in Steve, Steven and Stephen—cute that they have almost the same name, huh?—face similar conflicts. Stephen compulsively trades sexually explicit texts with one of the couple’s best friends Brian, and Steven retaliates by sleeping with an attractive waiter named Esteban. Meanwhile, Brian and his partner Matt are having a live-in threesome with their trainer, also named Steven. Do you sense a pattern here? The nearly identical names bit is stretched too much like many of Gerrard’s other gags such as the endless quoting of show lyrics. Also in the mix is Carrie, the token lesbian of the group who is afflicted with cancer and may get a movie deal out of her blog. Steven, Matt, and Carrie met as singing wait staff in a Broadway restaurant and have abandoned their attempts at musical-comedy careers. The theme of crushed dreams and mourning for lost youth is an intriguing one, but Gerrard fails to develop it.

The playwrights have the worthy concept of showing that gay people can be just as screwed up as their straight counterparts when faced with the challenge of building a socially sanctioned life with one partner, but the protagonists of Dada and Steve are defined by their sexual impulses, and their psychological motivations are not sufficiently explored to get us to care about them. In Dada, Alan comes across as a whiny narcissist, and in Steve we get sketchy show fans. A good therapist would work wonders with these people. Since they can afford nannies, weekends on Fire Island, private schools, and fabulous NYC apartments, you’d think they would try one.

Despite the thinness of the material, directors Scott Ellis (Dada) and Cynthia Nixon (Steve) deliver polished, sparkling stagings, and the casts gamely try to infuse their roles with the subtext the authors fail to provide. In Dada, John Benjamin Hickey almost makes the kvetchy Alan bearable, and Tammy Blanchard illuminates her cameo part of a pushy actor with an attractive energy. The Steve crowd has more opportunity for fun including a preshow sing-along at a standup piano. As the main couple, Matt McGrath and Malcolm Gets search in vain for the lovers beneath the quips and the song lyrics. Ashlie Atkinson is more successful in defining the caustic Carrie, and the hilarious Mario Cantone at least gets to cut up as Matt.

November 30, 2015

King Charles III

Music Box Theatre

Sylvia

Cort Theatre

On Your Feet! The Story of Emilio and Gloria Estefan

Marquis Theatre

Reviewed by David Sheward

Three recent openings offer examples of the most prevalent types of Broadway shows: the British snob hit (King Charles III), the star-vehicle revival (Sylvia), and the jukebox musical, Lifetime-TV biopic subdivision (On Your Feet! The Story of Emilio and Gloria Estefan). The first is perfection. The latter two have their share of flaws endemic to their genre but still contain pleasures of a kind.

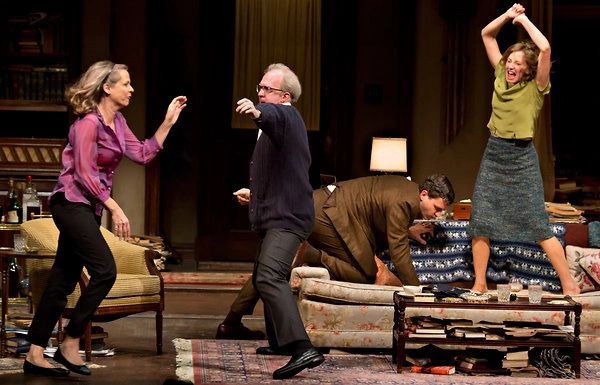

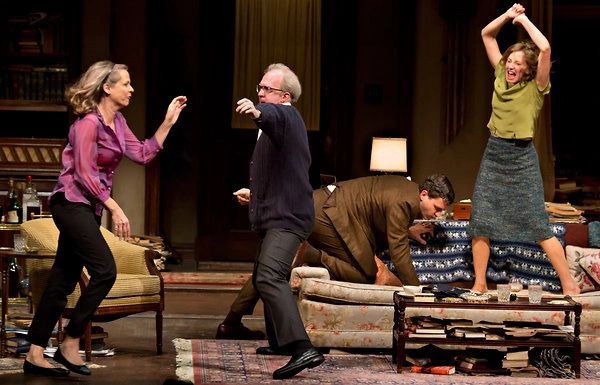

King Charles III arrives from London on a wave of adulation including the Olivier Award, and it’s all deserved. This is an ingenious political satire, acted and staged with just the right combination of passion and humor. Employing Shakespearean verse and referencing several of the Bard’s royal dramas, playwright Mike Bartlett imagines a near future when Queen Elizabeth II has died and her son, patient Prince Charles (the brilliant Tim Pigott-Smith) will finally ascend the throne. But a constitutional crisis arises when Charles refuses to sign Parliament’s bill curtailing freedom of the press. Machiavellian plots unfold as Prince William (a dashing Oliver Chris) and a Lady Macbeth–like Kate Middleton (the multidimensional Lydia Wilson) scheme to surpass the new king before his coronation. William’s brother, a fun-loving Prince Harry (a strong Richard Goulding) provides another wrinkle. Tired of endless public scrutiny, he begs his dad to allow him to renounce his title and join his girlfriend Jess (flinty Tafline Steen), a radical art student, as a private citizen. Both plot threads examine the perilous role of the monarchy in the 21st century. Bartlett asks hard questions such as: Is England still England without a crowned head, however ceremonial, atop its government?

I was pleasantly surprised at Bartlett’s clever and deft script, since I was less than enchanted by the last play of his I saw, the simplistic and condescending Cock, presented Off-Broadway in 2012. King Charles is light years away from that bisexual triangle comedy, where gay relationships were reduced to purely sexual connections. Government, media, history, and national identity are considered here in complex and fascinating detail. Rupert Goold’s sleek production and the gradually deepening performances draw us in. At first these royals seem like caricatures and are greeted with audience laughter, but as the stakes grow higher, they take on the Shakespearean qualities of ambition and tragedy their dialogue suggests. Pigott-Smith is shattering as the Richard II–ish Charles, initially a buffoon but increasing in dignity as he battles for his convictions against the forces of convenience.

From sharp satire, we move to comfy comedy. Sylvia is a pleasant enough little number from the prolific pen of A.R. Gurney, the chronicler of the American WASP in such keenly observed works as The Cocktail Hour, Love Letters and The Dining Room. Originally presented Off-Broadway in 1995, Sylvia concerns Greg, a disaffected money-market salesman whose midlife crisis manifests itself in a borderline obsessive affection for the titular stray mutt he finds in Central Park. The gimmick is the pooch is played by an actor, and she communicates with the other characters in intelligent speech. (Barks are replaced with Hey-Hey-Hey.) Gurney affectionately depicts Greg’s malaise and the anchor he finds in the Sylvia’s unconditional love, much to the dismay of his practical and jealous wife, Kate.

This revival has its share of chuckles and pathos, but the four-person ensemble is wildly off-balance in a rare disjointed staging by the usually proficient Daniel Sullivan. The nominal star is Matthew Broderick, whose wife, Sarah Jessica Parker, played Sylvia in the original production. The once-charming Ferris Bueller and adorably nebbishy Leo Bloom of The Producers is now in a middle-age funk not unlike Greg’s. In his last few Broadway outings such as It’s Only a Play and the musical Nice Work If You Can Get It, Broderick has been stiff and dull, bordering on zombie status. He does show signs of life here, but a regular pulse is hardly enough to sustain a leading role. As if to compensate, Robert Sella overplays his three supporting parts—including a boorish fellow dog-lover Greg meets in the park, an alcoholic female friend of Kate’s, and a transgender marriage counselor (this last one borders on the offensive).

The real star power is wielded by the two women of the cast: Tony winners Annaleigh Ashford as the canine female lead and Julie White as the put-upon spouse. The delightful Ashford has the showier role, flinging herself around David Rockwell’s cartoonish set with abandon, but both are brilliant. White captures Kate’s comic frustration with Sylvia’s slobbering, pooping, and stealing her husband’s affection without going overboard as Sella does. Because of the two actors’ dynamism, the focus shifts to the interspecies rivalry between Sylvia and Kate, and away from Greg’s male menopausal struggle. The most striking moment of the show comes at the end when Greg and Kate address the audience directly about their final days with Sylvia. White laughs to hide Kate’s reluctant but real love for the dog, and then she pushes back tears. It’s a beautiful ending. But Broderick’s Greg barely registers.

On Your Feet! The Story of Emilio and Gloria Estefan registers on the Richter scale, but not on the believability curve. This latest jukebox-bio musical is given a dance floor–worthy staging by director Jerry Mitchell and choreographer Sergio Trujillo, but Alexander Dinelaris’s book is strictly by the numbers. There is one genuinely funny line about Swedish fans at an Estefan concert being so white they look like Q-tips, and only the Act 1 finale displays any originality. In order to get their potential crossover hit “Conga” played on mainstreams stations, Gloria and Emilio play it anywhere they can get a booking—including a bar mitzvah, an Italian wedding, and a Shriners’ meeting (shades of Bye Bye Birdie). The partygoers at these various events joyously clash with audience members in the aisles in a riotous celebration.

Otherwise it’s business as usual: the Estefans rising to the top despite personal hardships, then suffering a catastrophic setback, to finally triumph with Gloria belting out an inspirational number at a music award ceremony. All of these events are true, yet they could have been depicted with more wit and imagination. Despite the shortcomings, the rhythm will definitely get you. Ana Villafane becomes a Broadway star in a blazing turn as Gloria, re-creating her vocals but not imitating them. Josh Segarra is a sexy and compelling Emilio, Andrea Burns gives steely support as Gloria’s disapproving mother, and Alma Cuervo is an endearing grandmother. On Your Feet! will get you on your feet, Sylvia will give you a few laughs, but King Charles III gives you a truly exciting night of theater.

Music Box Theatre

Sylvia

Cort Theatre

On Your Feet! The Story of Emilio and Gloria Estefan

Marquis Theatre

Reviewed by David Sheward

Three recent openings offer examples of the most prevalent types of Broadway shows: the British snob hit (King Charles III), the star-vehicle revival (Sylvia), and the jukebox musical, Lifetime-TV biopic subdivision (On Your Feet! The Story of Emilio and Gloria Estefan). The first is perfection. The latter two have their share of flaws endemic to their genre but still contain pleasures of a kind.

King Charles III arrives from London on a wave of adulation including the Olivier Award, and it’s all deserved. This is an ingenious political satire, acted and staged with just the right combination of passion and humor. Employing Shakespearean verse and referencing several of the Bard’s royal dramas, playwright Mike Bartlett imagines a near future when Queen Elizabeth II has died and her son, patient Prince Charles (the brilliant Tim Pigott-Smith) will finally ascend the throne. But a constitutional crisis arises when Charles refuses to sign Parliament’s bill curtailing freedom of the press. Machiavellian plots unfold as Prince William (a dashing Oliver Chris) and a Lady Macbeth–like Kate Middleton (the multidimensional Lydia Wilson) scheme to surpass the new king before his coronation. William’s brother, a fun-loving Prince Harry (a strong Richard Goulding) provides another wrinkle. Tired of endless public scrutiny, he begs his dad to allow him to renounce his title and join his girlfriend Jess (flinty Tafline Steen), a radical art student, as a private citizen. Both plot threads examine the perilous role of the monarchy in the 21st century. Bartlett asks hard questions such as: Is England still England without a crowned head, however ceremonial, atop its government?

I was pleasantly surprised at Bartlett’s clever and deft script, since I was less than enchanted by the last play of his I saw, the simplistic and condescending Cock, presented Off-Broadway in 2012. King Charles is light years away from that bisexual triangle comedy, where gay relationships were reduced to purely sexual connections. Government, media, history, and national identity are considered here in complex and fascinating detail. Rupert Goold’s sleek production and the gradually deepening performances draw us in. At first these royals seem like caricatures and are greeted with audience laughter, but as the stakes grow higher, they take on the Shakespearean qualities of ambition and tragedy their dialogue suggests. Pigott-Smith is shattering as the Richard II–ish Charles, initially a buffoon but increasing in dignity as he battles for his convictions against the forces of convenience.

From sharp satire, we move to comfy comedy. Sylvia is a pleasant enough little number from the prolific pen of A.R. Gurney, the chronicler of the American WASP in such keenly observed works as The Cocktail Hour, Love Letters and The Dining Room. Originally presented Off-Broadway in 1995, Sylvia concerns Greg, a disaffected money-market salesman whose midlife crisis manifests itself in a borderline obsessive affection for the titular stray mutt he finds in Central Park. The gimmick is the pooch is played by an actor, and she communicates with the other characters in intelligent speech. (Barks are replaced with Hey-Hey-Hey.) Gurney affectionately depicts Greg’s malaise and the anchor he finds in the Sylvia’s unconditional love, much to the dismay of his practical and jealous wife, Kate.

This revival has its share of chuckles and pathos, but the four-person ensemble is wildly off-balance in a rare disjointed staging by the usually proficient Daniel Sullivan. The nominal star is Matthew Broderick, whose wife, Sarah Jessica Parker, played Sylvia in the original production. The once-charming Ferris Bueller and adorably nebbishy Leo Bloom of The Producers is now in a middle-age funk not unlike Greg’s. In his last few Broadway outings such as It’s Only a Play and the musical Nice Work If You Can Get It, Broderick has been stiff and dull, bordering on zombie status. He does show signs of life here, but a regular pulse is hardly enough to sustain a leading role. As if to compensate, Robert Sella overplays his three supporting parts—including a boorish fellow dog-lover Greg meets in the park, an alcoholic female friend of Kate’s, and a transgender marriage counselor (this last one borders on the offensive).

The real star power is wielded by the two women of the cast: Tony winners Annaleigh Ashford as the canine female lead and Julie White as the put-upon spouse. The delightful Ashford has the showier role, flinging herself around David Rockwell’s cartoonish set with abandon, but both are brilliant. White captures Kate’s comic frustration with Sylvia’s slobbering, pooping, and stealing her husband’s affection without going overboard as Sella does. Because of the two actors’ dynamism, the focus shifts to the interspecies rivalry between Sylvia and Kate, and away from Greg’s male menopausal struggle. The most striking moment of the show comes at the end when Greg and Kate address the audience directly about their final days with Sylvia. White laughs to hide Kate’s reluctant but real love for the dog, and then she pushes back tears. It’s a beautiful ending. But Broderick’s Greg barely registers.

On Your Feet! The Story of Emilio and Gloria Estefan registers on the Richter scale, but not on the believability curve. This latest jukebox-bio musical is given a dance floor–worthy staging by director Jerry Mitchell and choreographer Sergio Trujillo, but Alexander Dinelaris’s book is strictly by the numbers. There is one genuinely funny line about Swedish fans at an Estefan concert being so white they look like Q-tips, and only the Act 1 finale displays any originality. In order to get their potential crossover hit “Conga” played on mainstreams stations, Gloria and Emilio play it anywhere they can get a booking—including a bar mitzvah, an Italian wedding, and a Shriners’ meeting (shades of Bye Bye Birdie). The partygoers at these various events joyously clash with audience members in the aisles in a riotous celebration.

Otherwise it’s business as usual: the Estefans rising to the top despite personal hardships, then suffering a catastrophic setback, to finally triumph with Gloria belting out an inspirational number at a music award ceremony. All of these events are true, yet they could have been depicted with more wit and imagination. Despite the shortcomings, the rhythm will definitely get you. Ana Villafane becomes a Broadway star in a blazing turn as Gloria, re-creating her vocals but not imitating them. Josh Segarra is a sexy and compelling Emilio, Andrea Burns gives steely support as Gloria’s disapproving mother, and Alma Cuervo is an endearing grandmother. On Your Feet! will get you on your feet, Sylvia will give you a few laughs, but King Charles III gives you a truly exciting night of theater.

November 8, 2015

Thérèse Raquin

Roundabout Theatre Company at Studio 54

The Humans

Roundabout Theatre Company at the Laura Pels Theatre

It’s the Halloween season and two productions from Roundabout Theatre Company explore scary demons. The big star vehicle, Thérèse Raquin, is full of fake emotion, while the Off-Broadway intimate drama The Humans is truly terrifying in its portrayal of the bumps and creaks in the night we all hear and fear.

The first act of Helen Edmundson’s stage adaptation of Emile Zola’s classic 1867 novel, Thérèse Raquin, from Roundabout at Studio 54 really had me going. I was totally enraptured by Keira Knightley’s nearly silent performance as the titular frustrated heroine, expressing her sexual and spiritual longing through body language and eloquent features. Thérèse is trapped in a passionless marriage to her bourgeois cousin Camille, first in a provincial backwater and then in a confining Paris apartment. Edmundson’s conceit is that Thérèse can only react to the stifling conditions of her life and remains silent as the oafish Camille and his control-freak mother order her existence. That is, until Camille’s dashing friend Laurent, a would-be painter, enters the picture. (Spoiler alert here if you have not read the novel or seen any of the numerous previous stage versions, including Harry Connick Jr.’s 2001 musical update Thou Shalt Not.) The connection between Thérèse and Laurent is electric, and they plot to eliminate Camille. The drowning scene on a real river is really scary; kudos to director Evan Cabnet and set designer Beowulf Boritt.

So far, so good, but in the second act Therese opens her mouth. Knightley and Matt Ryan as Laurent start overacting all over the place, and Cabnet turns a tragic tale of passion into an episode of Dark Shadows. The lovers become racked with guilt and imagine Camille’s accusing ghost haunting them as Josh Schmidt’s twisted sound design and Keith Parham’s haunted-house lighting grow more ominous. There are some effective moments, mostly provided by Boritt’s impressive set. Thérèse seems to be crushed by her all-black apartment as it descends from the flies, and she appears to soar when she meets Laurent in his attic, suspended above the stage amid a starry backdrop (Parham’s lighting achieves the right romantic tone here). Gabriel Ebert’s comically clueless Camille, Judith Light’s well-meaning Madame Raquin, and Jeff Still, David Patrick Kelly, and Mary Wiseman as a trio of shallow family friends provide welcome depth. But they cannot rescue this scream fest from the spook house.

Thérèse attempts to evoke genuine fear, but The Humans succeeds in doing so. Stephen Karam’s new play starts out like a dozen other dysfunctional-family works. The Blake clan reveals harsh secrets on Thanksgiving as the turkey is served and the wine flows. What sets this haunting and heartbreaking drama apart is the subtle depiction of the nightmares that invade and twist the lives of everyday people. The six characters’ fears for the future take various frighteningly familiar forms. Dad Erik obsesses over terrorist attacks and floods. Mother Deirdre forwards emails of dire scientific studies to her daughters: Aimee, a lawyer struggling with losing her lesbian lover, her job and her health, and Brigid, a young composer facing a dead-end career. The senile grandmother Fiona (“Momo”) is lost to dementia, and Richard, Brigid’s much older boyfriend, has recovered from depression but still has bizarre dreams. Still, those dreams are much less frightening than Erik’s, which involve a faceless woman and a forbidding tunnel.

During 90 intermissionless minutes, an expert cast, directed with subtlety by Joe Mantello, conveys the petty conflicts and major tragedies of these frightened people, beset by the shifting and uncertain landscape of modern America. Lights switch off, weird sounds emanate from all over Brigid and Richard’s spacious but crumbling Chinatown duplex (great set by David Zinn and sound by Fitz Patton), and the lives of the Blakes are gradually revealed as pitiful and desperate. The entire cast is top-rate with veterans Reed Birney and Jayne Houdyshell delivering their customary solid work. But Cassie Beck’s Aimee is outstanding in this standout ensemble. Her shattered, scattered cellphone call to an estranged girlfriend is a heartbreaking moment in an intensely real performance.

Just after it opened, The Humans announced its transfer to Broadway next year. It will be fascinated to see if it this disturbing, unflinching look at the way we live now succeeds on the Great White Way.

Roundabout Theatre Company at Studio 54

The Humans

Roundabout Theatre Company at the Laura Pels Theatre

It’s the Halloween season and two productions from Roundabout Theatre Company explore scary demons. The big star vehicle, Thérèse Raquin, is full of fake emotion, while the Off-Broadway intimate drama The Humans is truly terrifying in its portrayal of the bumps and creaks in the night we all hear and fear.

The first act of Helen Edmundson’s stage adaptation of Emile Zola’s classic 1867 novel, Thérèse Raquin, from Roundabout at Studio 54 really had me going. I was totally enraptured by Keira Knightley’s nearly silent performance as the titular frustrated heroine, expressing her sexual and spiritual longing through body language and eloquent features. Thérèse is trapped in a passionless marriage to her bourgeois cousin Camille, first in a provincial backwater and then in a confining Paris apartment. Edmundson’s conceit is that Thérèse can only react to the stifling conditions of her life and remains silent as the oafish Camille and his control-freak mother order her existence. That is, until Camille’s dashing friend Laurent, a would-be painter, enters the picture. (Spoiler alert here if you have not read the novel or seen any of the numerous previous stage versions, including Harry Connick Jr.’s 2001 musical update Thou Shalt Not.) The connection between Thérèse and Laurent is electric, and they plot to eliminate Camille. The drowning scene on a real river is really scary; kudos to director Evan Cabnet and set designer Beowulf Boritt.

So far, so good, but in the second act Therese opens her mouth. Knightley and Matt Ryan as Laurent start overacting all over the place, and Cabnet turns a tragic tale of passion into an episode of Dark Shadows. The lovers become racked with guilt and imagine Camille’s accusing ghost haunting them as Josh Schmidt’s twisted sound design and Keith Parham’s haunted-house lighting grow more ominous. There are some effective moments, mostly provided by Boritt’s impressive set. Thérèse seems to be crushed by her all-black apartment as it descends from the flies, and she appears to soar when she meets Laurent in his attic, suspended above the stage amid a starry backdrop (Parham’s lighting achieves the right romantic tone here). Gabriel Ebert’s comically clueless Camille, Judith Light’s well-meaning Madame Raquin, and Jeff Still, David Patrick Kelly, and Mary Wiseman as a trio of shallow family friends provide welcome depth. But they cannot rescue this scream fest from the spook house.

Thérèse attempts to evoke genuine fear, but The Humans succeeds in doing so. Stephen Karam’s new play starts out like a dozen other dysfunctional-family works. The Blake clan reveals harsh secrets on Thanksgiving as the turkey is served and the wine flows. What sets this haunting and heartbreaking drama apart is the subtle depiction of the nightmares that invade and twist the lives of everyday people. The six characters’ fears for the future take various frighteningly familiar forms. Dad Erik obsesses over terrorist attacks and floods. Mother Deirdre forwards emails of dire scientific studies to her daughters: Aimee, a lawyer struggling with losing her lesbian lover, her job and her health, and Brigid, a young composer facing a dead-end career. The senile grandmother Fiona (“Momo”) is lost to dementia, and Richard, Brigid’s much older boyfriend, has recovered from depression but still has bizarre dreams. Still, those dreams are much less frightening than Erik’s, which involve a faceless woman and a forbidding tunnel.

During 90 intermissionless minutes, an expert cast, directed with subtlety by Joe Mantello, conveys the petty conflicts and major tragedies of these frightened people, beset by the shifting and uncertain landscape of modern America. Lights switch off, weird sounds emanate from all over Brigid and Richard’s spacious but crumbling Chinatown duplex (great set by David Zinn and sound by Fitz Patton), and the lives of the Blakes are gradually revealed as pitiful and desperate. The entire cast is top-rate with veterans Reed Birney and Jayne Houdyshell delivering their customary solid work. But Cassie Beck’s Aimee is outstanding in this standout ensemble. Her shattered, scattered cellphone call to an estranged girlfriend is a heartbreaking moment in an intensely real performance.

Just after it opened, The Humans announced its transfer to Broadway next year. It will be fascinated to see if it this disturbing, unflinching look at the way we live now succeeds on the Great White Way.

Reviewed by David Sheward

October 30, 2015

October 30, 2015

Dames at Sea

Helen Hayes Theatre

Ripcord

Manhattan Theatre Club at City Center Stage I

Reviewed by David Sheward

A show doesn’t have to be a masterpiece to provide an enjoyable evening of theater. Case in point: Two recent openings may not win a shelf full of Tonys or a Pulitzer Prize, but they kept me entertained for their respective two hours’ traffic. Both Dames at Sea on Broadway at the Helen Hayes and Ripcord from Manhattan Theatre Club at its Off-Broadway berth at City Center employ familiar tropes. In the case of Dames, the director and cast execute cinema clichés with infectious charm, and in Ripcord playwright David Lindsay-Abaire expands on the familiar mismatched-roommates theme.

Dames is an affectionate spoof of 1930s movie musicals. It was first presented Off-Off-Broadway at Caffe Cino in 1966 as a one-act with a then-unknown Bernadette Peters. The clever cameo was lengthened, knocked an “Off” from its credentials when it moved to the Theatre de Lys (now the Lucille Lortel) two years later, and made a star out of Peters. The piece is basically an extended sketch like the ones they did on The Carol Burnett Show, sending up every plotline in the book—including the unknown kid going on for the star, the gutsy troupe surmounting incredible odds to put on a show, and the innocent ingénue winning the hero from the scheming leading lady. The fizzy songs by composer Jim Wise and lyricists George Haimsohn and Robin Miller offer just as many pastiche references as the book does. Gershwin, Porter, Berlin, Warren, and the team of Desylva, Brown, and Henderson all get the tribute treatment.

It’s as light as a soap bubble and just as lasting, sure to burst as soon as you hit the pavement outside the Helen Hayes. But while the hardworking cast keeps the bubble afloat, Dames is a delight. Director-choreographer Randy Skinner served as Gower Champion’s assistant on The Carol Burnett Show and staged the 2001 revival. He supplies the same kind of polished production values and tip-top taps for this miniature from the same template.

The six-member company captures the archetypes with precision and humor. Eloise Kropp's plucky Ruby, Carey Tedder’s earnest Dick, Danny Gardner’s goofy Lucky, and Mara Davi’s wisecracking Joan display amazing dance and comedic skills. John Bolton brilliantly doubles as the slave-driving director and the pompous ship’s captain. But all are second bananas to Lesli Margherita’s hilarious Mona Kent, the diva to end all divas. Margherita, the brainless ballroom-dancing mother from Matilda, can get a laugh just by walking across the stage with a ladder (the gag is Mona is off to fix her misspelled name on the marquee). The performer perfectly captures the narcissistic excesses of this spoiled star, covering up her lower-class roots with a ridiculous upper-crust accent. She opens the show with a boffo “Wall Street” (a knock-off of “We’re in the Money”), sends up every torch song ever written in “That Mister Man of Mine,” and perfectly pairs with Bolton on a witty satire of Porter’s “Begin the Beguine.” A dynamite dame in a dazzling Dames.

Just as Dames sounds like a rerun of Carol Burnett, Ripcord has the ring of an old Golden Girls segment. Grouchy Abby and good-natured Marilyn share a room in an assisted-living facility. The outgoing Marilyn is as pleased as punch with the arrangement, but ill-tempered Abby wants to be alone. They bet on who can make the other break her respective façade—first with Marilyn vacating or winning the bed by the window as the stakes. It sounds like sitcom fodder. But, as he did with his Fuddy Meers, Good People, Rabbit Hole, and Kimberly Akimbo, author David Lindsay-Abaire combines comedy with pathos for realistic depiction of life where the line between hilarity and heartache blurs.

Marilyn and her loving family maintain their quirky sense of humor even after we learn dark secrets of their shared lives. Abby is not just a comically nasty crone but also a deeply wounded woman who has come by her forbidding nature thanks to a series of devastating tragedies. Director David Hyde Pierce and the cast, led by a razor-sharp Holland Taylor as Abby and sweet-but-tough Marylouise Burke as Marilyn, tread a fine line between laughter and tears, achieving the perfect balance between the two. Slapstick is cheek by jowl with sorrow, and it works.

Helen Hayes Theatre

Ripcord

Manhattan Theatre Club at City Center Stage I

Reviewed by David Sheward

A show doesn’t have to be a masterpiece to provide an enjoyable evening of theater. Case in point: Two recent openings may not win a shelf full of Tonys or a Pulitzer Prize, but they kept me entertained for their respective two hours’ traffic. Both Dames at Sea on Broadway at the Helen Hayes and Ripcord from Manhattan Theatre Club at its Off-Broadway berth at City Center employ familiar tropes. In the case of Dames, the director and cast execute cinema clichés with infectious charm, and in Ripcord playwright David Lindsay-Abaire expands on the familiar mismatched-roommates theme.

Dames is an affectionate spoof of 1930s movie musicals. It was first presented Off-Off-Broadway at Caffe Cino in 1966 as a one-act with a then-unknown Bernadette Peters. The clever cameo was lengthened, knocked an “Off” from its credentials when it moved to the Theatre de Lys (now the Lucille Lortel) two years later, and made a star out of Peters. The piece is basically an extended sketch like the ones they did on The Carol Burnett Show, sending up every plotline in the book—including the unknown kid going on for the star, the gutsy troupe surmounting incredible odds to put on a show, and the innocent ingénue winning the hero from the scheming leading lady. The fizzy songs by composer Jim Wise and lyricists George Haimsohn and Robin Miller offer just as many pastiche references as the book does. Gershwin, Porter, Berlin, Warren, and the team of Desylva, Brown, and Henderson all get the tribute treatment.

It’s as light as a soap bubble and just as lasting, sure to burst as soon as you hit the pavement outside the Helen Hayes. But while the hardworking cast keeps the bubble afloat, Dames is a delight. Director-choreographer Randy Skinner served as Gower Champion’s assistant on The Carol Burnett Show and staged the 2001 revival. He supplies the same kind of polished production values and tip-top taps for this miniature from the same template.

The six-member company captures the archetypes with precision and humor. Eloise Kropp's plucky Ruby, Carey Tedder’s earnest Dick, Danny Gardner’s goofy Lucky, and Mara Davi’s wisecracking Joan display amazing dance and comedic skills. John Bolton brilliantly doubles as the slave-driving director and the pompous ship’s captain. But all are second bananas to Lesli Margherita’s hilarious Mona Kent, the diva to end all divas. Margherita, the brainless ballroom-dancing mother from Matilda, can get a laugh just by walking across the stage with a ladder (the gag is Mona is off to fix her misspelled name on the marquee). The performer perfectly captures the narcissistic excesses of this spoiled star, covering up her lower-class roots with a ridiculous upper-crust accent. She opens the show with a boffo “Wall Street” (a knock-off of “We’re in the Money”), sends up every torch song ever written in “That Mister Man of Mine,” and perfectly pairs with Bolton on a witty satire of Porter’s “Begin the Beguine.” A dynamite dame in a dazzling Dames.

Just as Dames sounds like a rerun of Carol Burnett, Ripcord has the ring of an old Golden Girls segment. Grouchy Abby and good-natured Marilyn share a room in an assisted-living facility. The outgoing Marilyn is as pleased as punch with the arrangement, but ill-tempered Abby wants to be alone. They bet on who can make the other break her respective façade—first with Marilyn vacating or winning the bed by the window as the stakes. It sounds like sitcom fodder. But, as he did with his Fuddy Meers, Good People, Rabbit Hole, and Kimberly Akimbo, author David Lindsay-Abaire combines comedy with pathos for realistic depiction of life where the line between hilarity and heartache blurs.

Marilyn and her loving family maintain their quirky sense of humor even after we learn dark secrets of their shared lives. Abby is not just a comically nasty crone but also a deeply wounded woman who has come by her forbidding nature thanks to a series of devastating tragedies. Director David Hyde Pierce and the cast, led by a razor-sharp Holland Taylor as Abby and sweet-but-tough Marylouise Burke as Marilyn, tread a fine line between laughter and tears, achieving the perfect balance between the two. Slapstick is cheek by jowl with sorrow, and it works.

October 28, 2015

Otello

Metropolitan Opera at Lincoln Center

Reviewed by David Sheward

Barlett Sher’s new production of Verdi’s Otello for the Metropolitan Opera begins with a bang. Lightning strikes and Luke Halls’s vivid video projections depict a violent storm at sea as Otello’s ship battles the elements making for Cyprus and his fateful deception with the duplicitous Iago. But this dynamic opening is followed by static staging with the huge chorus standing nearly motionless as Aleksandrs Antonecko in the title role stolidly holds forth. It takes quite a while for the production to regain its momentum, thanks largely to Zeljko Lucic’s powerful Iago and Sonya Yoncheva’s magnificently sung Desdemona.

Antonenko does create a stirring presence in the later acts as the Moor is caught in the grip of uncertain jealousy. His tenor is largely strongly supported, though there were a few wobbles, but his acting does not match the unwavering intensity of Lucic or the impassioned fluidity of Yoncheva’s rich soprano tones. Sher has chosen not to have his lead in dark make-up, thus eliminating Shakespeare’s racial dimension and diminishing the character’s alienation in an all-white society. (There have fascinating expressions of the play’s racial politics such a production starring Patrick Stewart in the title role with all the other characters played by African-Americans.)

Es Devlin’s set design also does not add to the tension. A series of transparent structures glides through a 19th-century seaport, supposedly reflecting the inner turmoil of the characters. Apart from one fascinating sequence as Otello eavesdrops on Iago and Cassio (a capable Dmitri Pattas), the see-through set pieces are not utilized to their fullest potential. Fortunately, Donald Holden’s awe-inspiring lighting provides subtle commentary as in a climactic Act 3 confrontation between the Moor and the visiting dignitaries of Venice. A dazzling sunset erupts as the full extent of Otello’s irrational behavior is revealed—a stunning moment in a vocally arresting but dramatically uneven production.

Metropolitan Opera at Lincoln Center

Reviewed by David Sheward

Barlett Sher’s new production of Verdi’s Otello for the Metropolitan Opera begins with a bang. Lightning strikes and Luke Halls’s vivid video projections depict a violent storm at sea as Otello’s ship battles the elements making for Cyprus and his fateful deception with the duplicitous Iago. But this dynamic opening is followed by static staging with the huge chorus standing nearly motionless as Aleksandrs Antonecko in the title role stolidly holds forth. It takes quite a while for the production to regain its momentum, thanks largely to Zeljko Lucic’s powerful Iago and Sonya Yoncheva’s magnificently sung Desdemona.

Antonenko does create a stirring presence in the later acts as the Moor is caught in the grip of uncertain jealousy. His tenor is largely strongly supported, though there were a few wobbles, but his acting does not match the unwavering intensity of Lucic or the impassioned fluidity of Yoncheva’s rich soprano tones. Sher has chosen not to have his lead in dark make-up, thus eliminating Shakespeare’s racial dimension and diminishing the character’s alienation in an all-white society. (There have fascinating expressions of the play’s racial politics such a production starring Patrick Stewart in the title role with all the other characters played by African-Americans.)

Es Devlin’s set design also does not add to the tension. A series of transparent structures glides through a 19th-century seaport, supposedly reflecting the inner turmoil of the characters. Apart from one fascinating sequence as Otello eavesdrops on Iago and Cassio (a capable Dmitri Pattas), the see-through set pieces are not utilized to their fullest potential. Fortunately, Donald Holden’s awe-inspiring lighting provides subtle commentary as in a climactic Act 3 confrontation between the Moor and the visiting dignitaries of Venice. A dazzling sunset erupts as the full extent of Otello’s irrational behavior is revealed—a stunning moment in a vocally arresting but dramatically uneven production.

October 19, 2015

Cloud Nine

Atlantic Theater Company

Barbecue

Public Theater

The Christians

Playwrights Horizons

Reviewed by David Sheward

Theatrical conventions are shattered in three Off-Broadway productions as playwrights explore the hot-button topics of race, gender, and religion. Two are contemporary (Robert O’Hara’s Barbecue and Lucas Hnath’s The Christians) and one is more than three decades old (Caryl Churchill’s Cloud Nine), but the latter is still the boldest and most innovative. Churchill’s works have always turned expectations on their heads. Cloud Nine was her first transatlantic hit, running Off-Broadway in a Tommy Tune–directed production for more than two years after a London production. The author plays with sexual stereotypes by having women play male parts and vice versa. She further stretches boundaries by having dead people enter the action and 100 years collapse into 25 without any of the characters’ batting an eye. She has played other weird tricks in later plays such as Top Girls, Fen, and Serious Money.

Here her theme is sex—both the activity and the biological differences in the human species. In the first act, a Victorian family represses all kinds of urges in a colonial African outpost. In the second act, the same family is only a quarter century older in modern London, and though the restrictive chains have been lifted, they are still tormented by their carnal drives. Churchill offers no easy answers nor observations, but compassionately charts the messy journeys of her confused Britons.

In James Macdonald’s intimate revival for Atlantic Theatre Company, the audience is seated close to the cast on wooden benches in designer Dane Laffrey’s in-the-round arena (and Gabriel Berry’s costumes define the characters and their attitudes). It’s a small, claustrophobic space, and you can feel the heat along with the characters. Seven versatile performers brilliantly play a variety of sexes, races, and persuasions. Brooke Bloom is particularly moving as an effeminate boy and then his own mother discovering the joys of self-pleasure. Izzie Steele, a Carey Mulligan lookalike, sharply conveys the desperate longings of two lesbians of different eras and a fiercely independent widow. Clarke Thorell is delightfully aggressive as a proper, pompous father and then a nasty tomboy of a girl.

Robert O’Hara also defies time and space in his examination of the impact of racism and homophobia in his plays Insurrection: Holding History and Bootycandy. In his newest work, Barbecue, at the Public Theatre, he takes a leaf out of Churchill’s book but bends and twists it in his own way. The play is set in a public park (like the second act of Cloud Nine) where a lower-middle-class family stages an intervention to get a drug-addicted sister to enter rehab. But is it the family black or white? At first, we don’t know for sure because alternate scenes feature both races. By switching from one to the other, O’Hara forces us to confront our prejudices. As the play progresses and additional layers of reality are added, our perspective shifts, and the author makes us consider the distortions imposed by media and pop culture. Kent Gash’s direction is wildly funny, as are the performances by a company as boisterous as the Cloud Nine crew. Tamberla Perry and Samantha Soule are given the juiciest opportunities as two versions of the junkie sibling, and they run with them. Kudos also to Paul Tazewell’s clever costumes, which subtly contrast the two families.

After sex and race, religion used to be the topic you were supposed to avoid in polite conversation. Lucas Hnath tackles this third rail of American discourse in his electrifying and scary The Christians. Just after the debts for his megachurch have been paid off, Pastor Bob announces he no longer believes in literal damnation and that God is all-forgiving to non-Christians, nonbelievers, and even Hitler. His congregation, his board of directors, and his wife slowly fall away as Bob continues to preach his personal vision, which runs contrary to the fire-and-brimstone stance of his rival Joshua, a former associate now starting his own ministry.

Hnath delivers a hard-hitting work on the necessity of hell for some people to do good. Like Dr. Stockmann in Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People, Pastor Bob becomes an outcast for pursuing what he perceives as the best possible course for his community. But he’s no unblemished saint. Hnath makes Bob a complex and flawed visionary, and Joshua is no fire-breathing bigot but a sincere advocate for his position. Andrew Garman and Larry Powell give multiple shadings to these two adversaries, and Emily Donahoe is stunningly compelling as a questioning parishioner. Complete with a choir, organ, stained-glass windows, and microphones, the action becomes a full-on Sunday service (the accurate setting is again by Dane Laffrey), staged with insight and power by Les Waters.

Like the previous two plays, The Christians covers a difficult theme in an unexpected format, offering new insights and provoking audiences to think differently—the goal of engaged and engaging theater.

Atlantic Theater Company

Barbecue

Public Theater

The Christians

Playwrights Horizons

Reviewed by David Sheward

Theatrical conventions are shattered in three Off-Broadway productions as playwrights explore the hot-button topics of race, gender, and religion. Two are contemporary (Robert O’Hara’s Barbecue and Lucas Hnath’s The Christians) and one is more than three decades old (Caryl Churchill’s Cloud Nine), but the latter is still the boldest and most innovative. Churchill’s works have always turned expectations on their heads. Cloud Nine was her first transatlantic hit, running Off-Broadway in a Tommy Tune–directed production for more than two years after a London production. The author plays with sexual stereotypes by having women play male parts and vice versa. She further stretches boundaries by having dead people enter the action and 100 years collapse into 25 without any of the characters’ batting an eye. She has played other weird tricks in later plays such as Top Girls, Fen, and Serious Money.

Here her theme is sex—both the activity and the biological differences in the human species. In the first act, a Victorian family represses all kinds of urges in a colonial African outpost. In the second act, the same family is only a quarter century older in modern London, and though the restrictive chains have been lifted, they are still tormented by their carnal drives. Churchill offers no easy answers nor observations, but compassionately charts the messy journeys of her confused Britons.

In James Macdonald’s intimate revival for Atlantic Theatre Company, the audience is seated close to the cast on wooden benches in designer Dane Laffrey’s in-the-round arena (and Gabriel Berry’s costumes define the characters and their attitudes). It’s a small, claustrophobic space, and you can feel the heat along with the characters. Seven versatile performers brilliantly play a variety of sexes, races, and persuasions. Brooke Bloom is particularly moving as an effeminate boy and then his own mother discovering the joys of self-pleasure. Izzie Steele, a Carey Mulligan lookalike, sharply conveys the desperate longings of two lesbians of different eras and a fiercely independent widow. Clarke Thorell is delightfully aggressive as a proper, pompous father and then a nasty tomboy of a girl.

Robert O’Hara also defies time and space in his examination of the impact of racism and homophobia in his plays Insurrection: Holding History and Bootycandy. In his newest work, Barbecue, at the Public Theatre, he takes a leaf out of Churchill’s book but bends and twists it in his own way. The play is set in a public park (like the second act of Cloud Nine) where a lower-middle-class family stages an intervention to get a drug-addicted sister to enter rehab. But is it the family black or white? At first, we don’t know for sure because alternate scenes feature both races. By switching from one to the other, O’Hara forces us to confront our prejudices. As the play progresses and additional layers of reality are added, our perspective shifts, and the author makes us consider the distortions imposed by media and pop culture. Kent Gash’s direction is wildly funny, as are the performances by a company as boisterous as the Cloud Nine crew. Tamberla Perry and Samantha Soule are given the juiciest opportunities as two versions of the junkie sibling, and they run with them. Kudos also to Paul Tazewell’s clever costumes, which subtly contrast the two families.

After sex and race, religion used to be the topic you were supposed to avoid in polite conversation. Lucas Hnath tackles this third rail of American discourse in his electrifying and scary The Christians. Just after the debts for his megachurch have been paid off, Pastor Bob announces he no longer believes in literal damnation and that God is all-forgiving to non-Christians, nonbelievers, and even Hitler. His congregation, his board of directors, and his wife slowly fall away as Bob continues to preach his personal vision, which runs contrary to the fire-and-brimstone stance of his rival Joshua, a former associate now starting his own ministry.

Hnath delivers a hard-hitting work on the necessity of hell for some people to do good. Like Dr. Stockmann in Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People, Pastor Bob becomes an outcast for pursuing what he perceives as the best possible course for his community. But he’s no unblemished saint. Hnath makes Bob a complex and flawed visionary, and Joshua is no fire-breathing bigot but a sincere advocate for his position. Andrew Garman and Larry Powell give multiple shadings to these two adversaries, and Emily Donahoe is stunningly compelling as a questioning parishioner. Complete with a choir, organ, stained-glass windows, and microphones, the action becomes a full-on Sunday service (the accurate setting is again by Dane Laffrey), staged with insight and power by Les Waters.

Like the previous two plays, The Christians covers a difficult theme in an unexpected format, offering new insights and provoking audiences to think differently—the goal of engaged and engaging theater.

October 19, 2015

Fool for Love

Manhattan Theatre Club at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

Old Times

Roundabout Theatre Company at the American Airlines Theatre

The Gin Game

John Golden Theatre

Reviewed by David Sheward

The fall Broadway season is in full swing with a trio of star-studded revivals of small-cast plays, each failing their author’s intent by varying degrees. Sam Shepard’s Fool for Love, Harold Pinter’s Old Times, and D.L. Coburn’s The Gin Game present dark visions of human connections and the clash of memory and personality. But only this production of Fool for Love approaches the play’s full impact, though it falls short.

At Fool for Love, as the curtain rises on Dane Laffrey’s desolate Mojave Desert motel setting, we know we’re in Shepard country—a lonely place where cowboys and good ol’ gals bluster to conceal their desperation. Three scruffy characters sit in silence for several seconds, but you can feel the tension. Nina Arianda and Sam Rockwell are May and Eddie, former lovers with a deeper, tragic bond. Gordon Joseph Weiss as The Old Man sits just outside the scene, not really there, but very present in the minds of the other two. May and Eddie have an explosive on-again, off-again relationship, which Eddie wants to renew as May is trying to get on with her life. She’s awaiting Martin, a new gentleman caller, but Eddie refuses to leave. Fireworks supposedly ensue when Martin shows up and we learn the true nature of the lovers’ link.

Director Daniel Aukin’s production for Manhattan Theatre Club, transferred from the Williamstown Theatre Festival, has the right atmosphere of dusty anguish, abetted by Laffrey’s sleazy setting, Justin Townsend’s stark lighting, and Ryan Rumery’s haunting sound design. But, despite solid performances, Arianda and Rockwell fail to generate the necessary lava-like temperatures to fully melt the audience’s butter. Weiss is an arresting figure as the spectral Old Man, and Tom Pelphrey is perfect as the confused Martin, an ordinary guy who’s wandered into an emotional minefield.

While Fool wants to be volcanic, Douglas Hodge’s distractingly showy production of Pinter’s Old Times for the Roundabout Theatre Company is frozen, literally. Christine Jones’s bizarre set is dominated by a slab of ice that serves as a perfect metaphor for this chilly staging. Pinter’s 1971 triangular drama concerns the slipperiness of recollection. Married Deeley and Kate entertain Anna, Kate’s friend and roommate from their early days in London. As the weird evening progress, bits of the past slip out, and a hazy, uncertain puzzle emerges. We don’t know what’s true and what isn’t. Did Deeley know Anna in the past? Is Anna dead? Did Anna steal Kate’s underwear and were they more than just flatmates?

Hodge directs a leering Clive Owen, an overacting Eve Best, and an arch Kate Reilly to play the rivalries and power struggles right on the surface rather than burying them in subtext as in most Pinter productions. In addition to that hunk of ice, Jones’s set features rock formations, a revolving living room, and an enormous backdrop of concentric circles, all of which remove us from the central action. The outsized environment seems more appropriate for a Wagnerian opera directed by Robert Wilson. Strobe lights and an intrusive rock underscore by Radiohead front man Thom Yorke further push us away from Pinter’s subtle conundrum of a play.

The Gin Game also disappoints. D.L. Coburn’s Pulitzer Prize winner for 1978 returns to Broadway with two highly touted stars: James Earl Jones and Cicely Tyson. The casting might lead you to expect a powerhouse confrontation, but Leonard Foglia’s staging offers a sitcom. Jones and Tyson are Weller and Fonsia, a pair of abandoned senior citizens playing gin in a depressing elder residence (wonderfully detailed set by Riccardo Hernandez). They attempt to become friends, but Fonsia’s endless winning streak sets off Weller’s explosive temper. The game is a metaphor for the mismatched couple’s extended relationships with their now-absent families—Weller cannot deal with unexpected losses, while Fonsia cannot resist judging and controlling. It’s no surprise these unpleasant people have no visitors. But Tyson plays Fonsia as a sweet old lady, only slightly showing her mean streak. Jones does not succumb to such tricks and makes Weller a sharp-witted but difficult codger whose inner grouch pops out at the slightest provocation.

As a result, Jones’s Weller comes across a bully menacing Tyson’s coquettish Fonsia, and we get an episode of The Golden Girls, complete with old-age jokes, rather than a slyly observed comedy of two lonely individuals unable to escape their self-imposed isolation. There are plenty of laughs, but The Gin Game, like the other recent openings, deserved to be dealt a better hand.

Manhattan Theatre Club at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

Old Times

Roundabout Theatre Company at the American Airlines Theatre

The Gin Game

John Golden Theatre

Reviewed by David Sheward

The fall Broadway season is in full swing with a trio of star-studded revivals of small-cast plays, each failing their author’s intent by varying degrees. Sam Shepard’s Fool for Love, Harold Pinter’s Old Times, and D.L. Coburn’s The Gin Game present dark visions of human connections and the clash of memory and personality. But only this production of Fool for Love approaches the play’s full impact, though it falls short.

At Fool for Love, as the curtain rises on Dane Laffrey’s desolate Mojave Desert motel setting, we know we’re in Shepard country—a lonely place where cowboys and good ol’ gals bluster to conceal their desperation. Three scruffy characters sit in silence for several seconds, but you can feel the tension. Nina Arianda and Sam Rockwell are May and Eddie, former lovers with a deeper, tragic bond. Gordon Joseph Weiss as The Old Man sits just outside the scene, not really there, but very present in the minds of the other two. May and Eddie have an explosive on-again, off-again relationship, which Eddie wants to renew as May is trying to get on with her life. She’s awaiting Martin, a new gentleman caller, but Eddie refuses to leave. Fireworks supposedly ensue when Martin shows up and we learn the true nature of the lovers’ link.

Director Daniel Aukin’s production for Manhattan Theatre Club, transferred from the Williamstown Theatre Festival, has the right atmosphere of dusty anguish, abetted by Laffrey’s sleazy setting, Justin Townsend’s stark lighting, and Ryan Rumery’s haunting sound design. But, despite solid performances, Arianda and Rockwell fail to generate the necessary lava-like temperatures to fully melt the audience’s butter. Weiss is an arresting figure as the spectral Old Man, and Tom Pelphrey is perfect as the confused Martin, an ordinary guy who’s wandered into an emotional minefield.

While Fool wants to be volcanic, Douglas Hodge’s distractingly showy production of Pinter’s Old Times for the Roundabout Theatre Company is frozen, literally. Christine Jones’s bizarre set is dominated by a slab of ice that serves as a perfect metaphor for this chilly staging. Pinter’s 1971 triangular drama concerns the slipperiness of recollection. Married Deeley and Kate entertain Anna, Kate’s friend and roommate from their early days in London. As the weird evening progress, bits of the past slip out, and a hazy, uncertain puzzle emerges. We don’t know what’s true and what isn’t. Did Deeley know Anna in the past? Is Anna dead? Did Anna steal Kate’s underwear and were they more than just flatmates?

Hodge directs a leering Clive Owen, an overacting Eve Best, and an arch Kate Reilly to play the rivalries and power struggles right on the surface rather than burying them in subtext as in most Pinter productions. In addition to that hunk of ice, Jones’s set features rock formations, a revolving living room, and an enormous backdrop of concentric circles, all of which remove us from the central action. The outsized environment seems more appropriate for a Wagnerian opera directed by Robert Wilson. Strobe lights and an intrusive rock underscore by Radiohead front man Thom Yorke further push us away from Pinter’s subtle conundrum of a play.

The Gin Game also disappoints. D.L. Coburn’s Pulitzer Prize winner for 1978 returns to Broadway with two highly touted stars: James Earl Jones and Cicely Tyson. The casting might lead you to expect a powerhouse confrontation, but Leonard Foglia’s staging offers a sitcom. Jones and Tyson are Weller and Fonsia, a pair of abandoned senior citizens playing gin in a depressing elder residence (wonderfully detailed set by Riccardo Hernandez). They attempt to become friends, but Fonsia’s endless winning streak sets off Weller’s explosive temper. The game is a metaphor for the mismatched couple’s extended relationships with their now-absent families—Weller cannot deal with unexpected losses, while Fonsia cannot resist judging and controlling. It’s no surprise these unpleasant people have no visitors. But Tyson plays Fonsia as a sweet old lady, only slightly showing her mean streak. Jones does not succumb to such tricks and makes Weller a sharp-witted but difficult codger whose inner grouch pops out at the slightest provocation.

As a result, Jones’s Weller comes across a bully menacing Tyson’s coquettish Fonsia, and we get an episode of The Golden Girls, complete with old-age jokes, rather than a slyly observed comedy of two lonely individuals unable to escape their self-imposed isolation. There are plenty of laughs, but The Gin Game, like the other recent openings, deserved to be dealt a better hand.

October 14, 2015

Spring Awakening

Brooks Atkinson Theatre

Daddy Long Legs

Davenport Theatre

Reviewed by David Sheward

Though the memory of Spring Awakening is still green—the original Broadway run of the electric rock musical ended only six years ago—Michael Arden’s jagged and heartfelt rendition for Deaf West Theatre, transferred to Broadway after a Los Angeles engagement, makes it feel like a totally different, brand-new show. The juxtaposition of the story’s 1891 setting and the intense, heart-pumping, contemporary score by Duncan Sheik and Steven Sater remains fresh, but the added element of a combined deaf and hearing cast gives Spring an extra jolt. Sater’s book, derived from Frank Wedekind’s original play, focuses on a group of German teens discovering sexual urges that the staid adult society pushes them to either ignore or repress—with tragic results.

Arden explains in a program note that 11 years before the publication of Wedekind’s explosive play, the deaf community was dealt a serious blow at an education conference in Milan. The attendees passed a resolution advocating lip reading and attempting speech over sign language, forcing deaf students to imitate their hearing peers rather than developing communication skills of their own. The production has the oppressive adults not listening to the youngsters both figuratively and literally.

This conflict is most sharply felt in a classroom scene where a tyrannical schoolmaster (a chilling Patrick Page) forces his deaf pupils to speak Latin translations rather than sign them. He mocks their gestures and their imperfect voices with shaming brutality. The pressure to conform— whether in speech or sexuality—pervades Arden’s production. Many of the roles are cast with deaf performers in period clothes while hearing actors dressed in modern duds provide their voices, acting as their caged modern selves trapped in the puritanical past. Dialogue is either signed or projected onto Dane Laffrey’s industrial nightmare of a set, as words and signs meld and overlap through Arden’s eloquent staging and Spencer Liff’s poetic choreography.

Interestingly, the lead roles are played by unknowns, while Broadway, film, and TV vets take supporting turns. The main character Melchior, a rebellious student seeking to throw off the restrictions of his elders, is played by the vibrant Austin P. McKenzie, a hearing actor fluent in sign language. He makes this anguished rebel serve as a bridge between the hearing and deaf worlds. Melchior’s equally distraught sweetheart, Wendla, is given passionate life by Sandra Mae Frank and sensitive voice by Katie Boeck.

Daniel N. Durant makes an intense Moritz, sort of a Sal Mineo to Melchior’s James Dean, and Alex Boniello provides his pained vocals. Andy Mientus and Krysta Rodriguez, both breakout performers in earlier Broadway productions and the TV series Smash, are arresting as the smug Hanschen and the lost Ilsa. The adult roles are shared by the hearing Page and Camryn Manheim and the deaf Russell Harvard and Marlee Matlin. Page, Manheim, and Harvard have moments of impact, but the Oscar-winning Matlin is underused as Melchior’s compassionate mother.

While Spring Awakening is a refreshing challenge to the rigid Broadway template (still firmly in place despite game changers like Hamilton and Fun Home), Off-Broadway’s Daddy Long Legs is an unimaginative miniature employing almost every Main Stem cliché, musically and dramatically. Ironically, this two-hander also deals with a young protagonist searching for identity in restrictive era (in this case America in the first decade of the 20th century). Jean Webster’s original 1912 novel has previously been adapted into lighthearted movie musicals with Shirley Temple (Curly Top, 1935) and Leslie Caron and Fred Astaire (1955). Composer-lyricist Paul Gordon and book author-director John Caird worked on a short-lived Broadway version of Jane Eyre, and Caird collaborated on Les Miz. Daddy employs the same kind of soupy romantic score and soapy libretto. The only unusual music can be heard during a brief section of a comic song about snobby New Yorkers.

The story may have been charming in 1912, but it lacks tension and surprise today. Jerusha Abbot, an orphan girl, writes letters to an unknown benefactor she assumes to be an avuncular old man, but he turns out to be her young suitor, the wealthy but noble-hearted Jervis Pendleton III. Fortunately, Megan McGinnis and Paul Alexander Nolan endow the two roles with wit and rich voice, making this postcard-sized show bearable for an overlong two acts.

Brooks Atkinson Theatre

Daddy Long Legs

Davenport Theatre

Reviewed by David Sheward

Though the memory of Spring Awakening is still green—the original Broadway run of the electric rock musical ended only six years ago—Michael Arden’s jagged and heartfelt rendition for Deaf West Theatre, transferred to Broadway after a Los Angeles engagement, makes it feel like a totally different, brand-new show. The juxtaposition of the story’s 1891 setting and the intense, heart-pumping, contemporary score by Duncan Sheik and Steven Sater remains fresh, but the added element of a combined deaf and hearing cast gives Spring an extra jolt. Sater’s book, derived from Frank Wedekind’s original play, focuses on a group of German teens discovering sexual urges that the staid adult society pushes them to either ignore or repress—with tragic results.

Arden explains in a program note that 11 years before the publication of Wedekind’s explosive play, the deaf community was dealt a serious blow at an education conference in Milan. The attendees passed a resolution advocating lip reading and attempting speech over sign language, forcing deaf students to imitate their hearing peers rather than developing communication skills of their own. The production has the oppressive adults not listening to the youngsters both figuratively and literally.

This conflict is most sharply felt in a classroom scene where a tyrannical schoolmaster (a chilling Patrick Page) forces his deaf pupils to speak Latin translations rather than sign them. He mocks their gestures and their imperfect voices with shaming brutality. The pressure to conform— whether in speech or sexuality—pervades Arden’s production. Many of the roles are cast with deaf performers in period clothes while hearing actors dressed in modern duds provide their voices, acting as their caged modern selves trapped in the puritanical past. Dialogue is either signed or projected onto Dane Laffrey’s industrial nightmare of a set, as words and signs meld and overlap through Arden’s eloquent staging and Spencer Liff’s poetic choreography.

Interestingly, the lead roles are played by unknowns, while Broadway, film, and TV vets take supporting turns. The main character Melchior, a rebellious student seeking to throw off the restrictions of his elders, is played by the vibrant Austin P. McKenzie, a hearing actor fluent in sign language. He makes this anguished rebel serve as a bridge between the hearing and deaf worlds. Melchior’s equally distraught sweetheart, Wendla, is given passionate life by Sandra Mae Frank and sensitive voice by Katie Boeck.

Daniel N. Durant makes an intense Moritz, sort of a Sal Mineo to Melchior’s James Dean, and Alex Boniello provides his pained vocals. Andy Mientus and Krysta Rodriguez, both breakout performers in earlier Broadway productions and the TV series Smash, are arresting as the smug Hanschen and the lost Ilsa. The adult roles are shared by the hearing Page and Camryn Manheim and the deaf Russell Harvard and Marlee Matlin. Page, Manheim, and Harvard have moments of impact, but the Oscar-winning Matlin is underused as Melchior’s compassionate mother.