Arts In LA

Dance in LA

Ballet Review

The Nutcracker

American Ballet Theatre at Segerstrom Center for the Arts

Reviewed by Dany Margolies

Kellan Hayag as the Nutcracker and Lani Mefford as Clara

Photo by Paul Rodriguez/Orange County Register

Though most ballet lovers love it, The Nutcracker is a confusing jumble of a ballet. In American Ballet Theatre’s current version, thankfully still set to the Tchaikovsky score, choreographer Alexei Ratmansky has done little to untangle the jumble. By its end, we know three things about Ratmansky: He has an iconoclastic streak, he’s interested in egalitarianism, and he loves soubresauts (little jumps in which the feet tuck up).

On the ballet’s opening night at Segerstrom Center for the Arts, the ABT pros looked like they had jet lag. On the other hand, the kids onstage—students from American Ballet Theatre William J. Gillespie School at Segerstrom Center for the Arts—looked like pros. This is American Ballet Theatre, for Christmas’ sake. The leads shouldn’t be hopping to finish pirouettes. The corps should stay tidily together. And all should have that star quality that says, “We are deservedly the best in the country if not in the world.”

The children, however, shone. They dance in time. They stay in line. And those lines and patterns are sophisticated and complicated even for adults. The students display beautiful carriage and épaulement (relative position of head and shoulders) while their feet work hard.

Ratmansky sets his first scene in the Stahlbaum family’s kitchen. The frantic staff tries to prepare for a party while the tiny mouse ensconced under the table is adorably defiant (danced by young Andrew Dove, who proves that physical comedians are born, not made).

The party swings into action, with swirling masses of kids and gifts and tipsy adults. Little Clara (Lani Mefford) and her obnoxious brother Fritz (Salvatore Lodi) mingle with the guests, until the apparently uninvited Drosselmeyer (Roman Zhurbin) arrives with major giftage: life-size dolls. Columbine (Cassandra Trenary) and Harlequin (Arron Scott) appear in black-and-white outfits, among the most-striking of Richard Hudson’s lavish costuming (he also designed the scenery here). Next comes the soldier Recruit (Luis Ribagorda), sometimes danced as a solo but here joined by the Canteen Keeper (Courtney Lavine), who shares the energetic choreography. Then, Drosselmeyer gives Clara a toy Nutcracker, which through stagecraft appears life-size and toy-size throughout the scene.

Clara, sad to head to bed, seems to awaken to an infestation of mice. In marches a battalion of toy soldiers (the young students again) led by the Nutcracker, who turns out to be “real” (Kellan Hayag). With help from Clara, who tosses her shoe into the fray, he slays the Mouse King (Thomas Forster).

Young Clara rejects a friendly advance from the young Nutcracker. But then we see a grownup Princess Clara and her Nutcracker Prince (ABT principals Hee Seo and Cory Stearns), and they’re in love. The younger pair find themselves snowed in. The snow frightens Clara. Those bouncy soubresauts of the 24 corps de ballet Snowflakes may frighten traditionalists. Drosselmeyer sends in a sleigh to rescue the two youngsters and propel them toward Act 2.

The Snowflakes and their soubresauts

Photo by Paul Rodriguez/Orange County Register

That act begins with byplay between four boys and four girls, trying to play it cool as the boys ask the girls to dance. Then we see the Kingdom of the Sweets in rehearsal mode. Wait, are those Bees, drawn to all the sugary morsels? Four men in black velveteen tights, black frockcoats, yellow-and-black striped vests, and yellow helmets topped by deely boppers certainly attract our attention. The young Nutcracker reenacts Clara’s shoe-throwing rescue, the moment nearly lost in the busyness, or in this case buzzy-ness, surrounding the miming.

Then comes the traditional parade of international characters. The lackluster Spanish dancers are covered head to toe in bulky costuming. The usually droning Arabian dance gets a twist here, as four wives prove an unhappy fantasy for their husband (Forster). The Chinese couple is a socialist treat, as man and woman lift each other equally (Skylar Brandt, Joseph Gorak). But the three Russians are a bland Three Stooges, a waste of great music and good dancers (Alexei Agoudine, Ribagorda, Scott). The reed pipes music is given over to a quintet Ratmansky calls the Nutcracker’s Sisters. They look more like female leprechauns, in green-and-white costuming with jauntily cocked top hats. Thank goodness the kids return to the stage as Polichinelles who escaped from under the towering skirt of Mother Ginger (Duncan Lyle).

Some of this ballet’s most-beautiful music is Waltz of the Flowers. The solo portion, customarily choreographed for the Dew Drop Fairy or an equivalent, here is given to those Bees. Well, in all fairness, men finally get to dance to that glorious music. So do 16 corps members as Flowers, but they appear careless, their raised legs at different heights, their jumps not in unison.

Grown Clara and the Nutcracker Prince dance the pas de deux traditionally the realm of the Sugar Plum Fairy (hard to find here, but embodied in an Act 1 program credit). Ratmansky leaves intact some of the original 1892 Mariinsky version, including a concluding fish dive, safe and uninspired here. The two pas de deux solos seem not to go with, let alone enhance, the music. Ratmansky takes symmetrical music and makes it seem asymmetrical, which is intriguing but ultimately unsatisfying. The best to be said of maestro Ormsby Wilkins and the Pacific Symphony is that they don’t overwhelm the dancing.

Someone needs to make American Ballet Theatre great again. The company would be wise to eventually bet on some of the kids.

December 15, 2018

Published with kind permission of Orange County Register

Ballet Review

Swan Lake

Los Angeles Ballet

Reviewed by Dany Margolies

Photo by Reed Hutchinson

Swan Lake is undeniably a world-famous ballet. Ask people across the globe who know a bit about ballet to hum a few bars of the Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky score, and they’re sure to come up with Act 2’s main theme, if not more. Or show them an image of the Swan Queen, in her white-feathered headdress and feather-flocked tutu, her arms undulating, and they’ll quickly name the ballet.

But what does it take to mount a world-class production of it? Any company, even without its own stellar prima ballerina and premier danseur, can always hire guest stars. Or, more impressively, it can lean on its own corps dancers. At the opening-night performance of Los Angeles Ballet’s Swan Lake, at Glendale’s Alex Theatre, the corps came through.

With choreography here by co-artistic directors Thordal Christensen and Colleen Neary after Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov, the story centers on Prince Siegfried, who for his 21st birthday is given a party but told by the queen that he must choose a bride. The queen then gives him a jewel-encrusted crossbow, and he and his inebriated friends head lakeside to hunt birds.

In Act 2, Siegfried comes across a flock of women who, under a spell from the immutably evil Von Rothbart, appear in the form of white swans, led by the swan queen Odette. Siegfried falls in love with Odette and promises her his eternal fidelity, which can break the spell.

In Act 3, Siegfried is at his birthday ball the next evening where he must find a wife. But the pretty princesses from other nations can’t take his mind off Odette. Suddenly, in bursts Von Rothbart and his daughter Odile, who looks exactly like Odette but clad in black. Siegfried, deceived, asks his mother for permission to marry Odile. He then discovers his fatal breach of promise.

In Act 4, the prince returns to the lake to face the betrayed Odette.

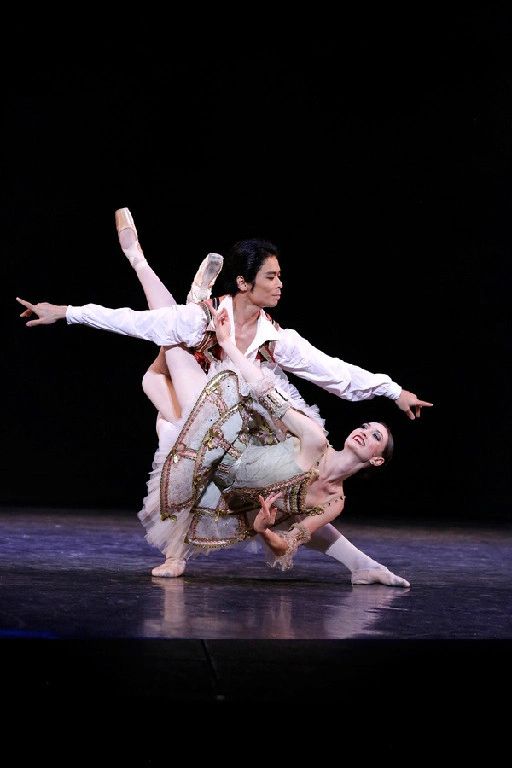

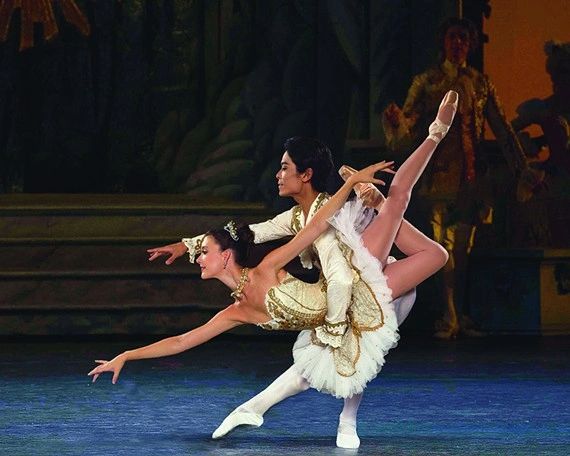

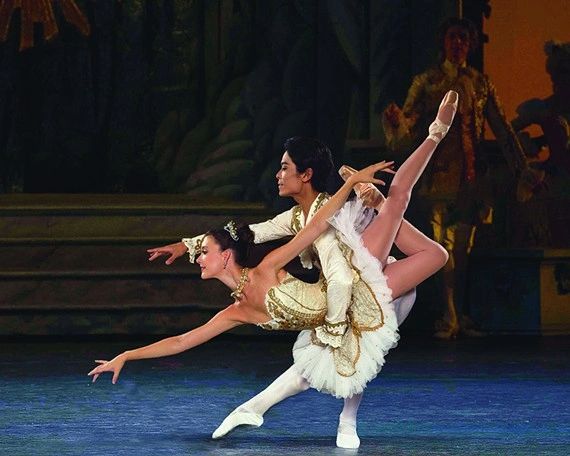

Kenta Shimizu and Petra Conti

Photo by Reed Hutchinson

LAB’s production begins with a Jester, and Akimitsu Yahata sets the bar high, with bounding technique and comedic chops. But the male corps of six, dancing in exact unison, starts to establish the pattern of corps excellence here. The peasant trio is performed satisfyingly cleanly, if somewhat cautiously, by Laura Chachich, Jasmine Perry and Tigran Sargsyan (who also serves as Siegfried’s friend Benno). Kenta Shimizu dances the role of Prince Siegfried, and Petra Conti dances Odette and Odile. These two principals are technically clean and proficient. Neither is particularly exciting. That could be because the story is muddy here. The prince starts out as a relatively contented soul. The swan queen starts out as not particularly distressed. And so not much character arc is available to them. However, Conti certainly sizzles as Odile in Act 3. Also troubling, even in other productions, is why the queen (Neary) shows no alarm when her son’s potential father-in-law Von Rothbart (Zheng Hua Li, an excellent dancer-actor hidden here under overwhelming costuming and dim lighting) is clearly so Machiavellian.

LAB’s curtain rises on each act to reveal a different set (scenery and costumes courtesy of Oregon Ballet Theatre). And those sets are elaborate. Apparently that explains the three 20- to 30-minute intermissions between acts. No matter. This production has one stellar asset that’s rare to find and more than worth waiting for.

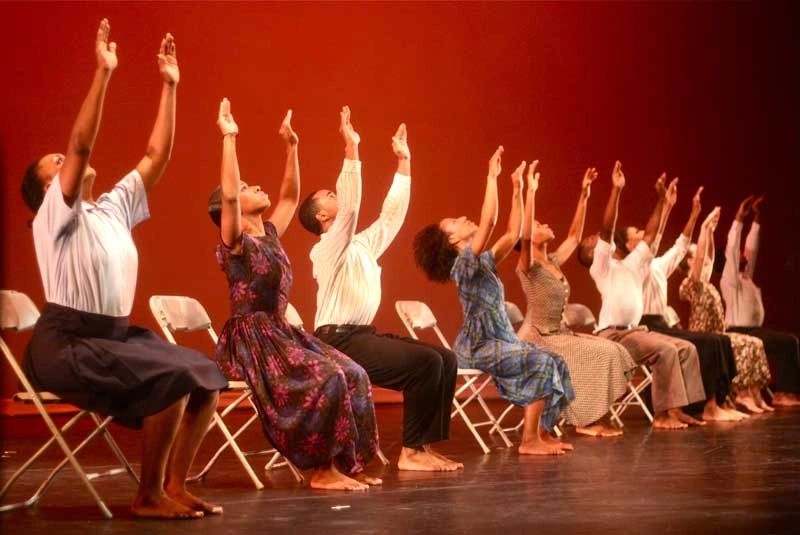

It takes dig-down-deep grit and hours upon hours of discipline to move in unison as the women of the swan corps did on opening night. It also takes a sharp eye and firm but not terrifying hand to coax dancers, trained in schools across the nation and the globe, into thrillingly identical musicality and lines. Los Angeles can be rightfully proud that this unison—this understanding of musicality and subjugation of individual egos, this utter presence and intelligence to fix spacing on the go without benefit of mirrors and second chances—lifts this production into world class.

March 5, 2018

Republished courtesy of Los Angeles Daily News

Ballet Review

Modern Moves

Los Angeles Ballet

Reviewed by Dany Margolies

Petra Conti, Tigran Sargsyan, and Kenta Shimizu in Les Chambres des Jacques

Photo by Reed Hutchinson

Two steps forward, one step back. That’s a dance pattern, but it’s also a pattern of history. Los Angeles Ballet titles its current production Modern Moves. The company takes two daring steps forward, staging two company premieres of contemporary pieces. Then it takes a retrospective step back, reviving a piece by the undisputed grandfather of modernist ballets, George Balanchine (1904–1983).

The evening begins with excerpts from Les Chambres des Jacques (translatable as The Rooms of the Jacks), choreographed by Aszure Barton in 2006. Perhaps the full work would have explained more, but the 25 minutes of these excerpts only hint at possible meanings. And so we watch, eyes magnetized to the stage. The choreography is as eccentric as the piece’s music—by Gilles Vigneault, Antonio Vivaldi, Les Yeux Noirs, The Cracow Klezmer Band and Alberto Iglesias. And yet it feels rooted in classical dance forms. Solos, duets and full ensembles provide the structure. From there, Barton deconstructs basic human movement, which she apparently finds endlessly interesting and inspiring. And because the company dances the work with full joyous commitment and strong technique, the audience finds it interesting and inspiring.

Clad in jacket and slacks, Clay Murray opens the show and sets a high bar with his fiendishly difficult solo. He flails, he distorts, he torques in perpetual motion. Murray soon will be stellar. He’s not there yet. Kenta Shimizu is stellar. His solo displays dancerly maturity. His movements are finished: They end purposefully, they are polished. He knows which ones to emphasize, which to make subtle. Unusual for programming, the piece closes with a solo, here by Tigran Sargsyan, who moves with velvety athleticism. When he emits a silent scream, we hear it. And here we realize perhaps the piece has been about the flirtations and frustrations of romance.

Barton creates a strange yet strangely familiar world. The men sniff the women, the women wriggle provocatively. Costume design by Robyn Clarke after Anne-Marie Veevaete’s originals puts the women in a shortened version of 19th-century undergarments, the men in various styles of outerwear. These might not be the most modern of moves. One step back.

In 2006, Alejandro Cerrudo choreographed Lickety-Split to music by Devendra Banhart. Romantic love again seems at the heart of this 20-minute piece. Cerrudo focuses more on the visuality of movement, less on conveying specific ideas to us, though, like Barton, he captures our interest, also thanks to the dancers’ intensity. Jasmine Perry and Dallas Finley enchant as a serene couple, perhaps newly attached, certainly young. Leah McCall and Joshua Brown display remarkable dynamics as a frenetic couple, McCall repeatedly wringing her hands over her head. Bianca Bulle and Sargsyan seem to be the couple who stay together through humor: Memorably, she lets him bonk his head on her bum. Though the dancing is again flawless, and though the dancers clearly relish the opportunity to break ballet rules, the piece leaves the impression of 1950s pairings and partnerings. One step back.

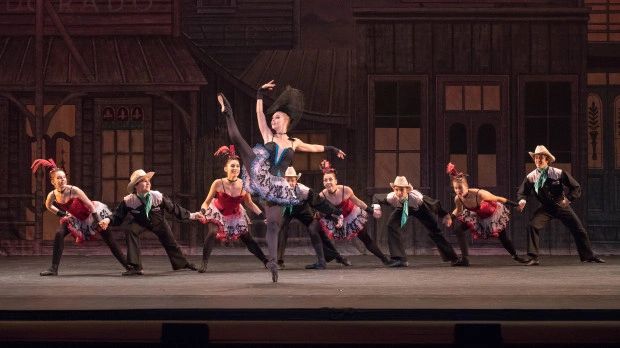

Bianca Bulle and the corps in Western Symphony

Photo by Reed Hutchinson

Perhaps Balanchine wanted a respite from his serious, abstract works, so he looked to the American West for inspiration, choreographing Western Symphony in 1954. Its music, by Hershy Kay, orchestrates familiar folk tunes, including “Red River Valley” and “Good Night Ladies.” But around the time Laura Chachich and Eris Nezha enter and she’s dressed in lilac (color-coded costuming by Laura Day “after” Balanchine’s famed artistic partner Karinska), we begin to catch on to Balanchine’s game. He balletically deconstructs French and Russian ballets, to giggle-inducing effect.

After Chachich and Nezha’s bounding “allegro” (here Balanchine names sections after musical movements) comes the wonderfully steely Petra Conti, wearing pewter, and Sargsyan, with impressive partnering, in the “adagio” that seems to gently mock Giselle and Swan Lake. The “scherzo” of the original, rarely seen since 1960, remains absent here. Bulle and Shimizu get their hilarious digs in during their “rondo,” though most notable is her Ascot-worthy hat, most of which is removed backstage before she re-emerges for her fouettés (the whipping turns on one leg), so obligatory in the classics. No wonder the humorless French and Russian critics lambasted Western Symphony when it arrived on their stages. Here, the entire evening is two steps forward and promenade home for Los Angeles Ballet.

October 18, 2018

Reprinted courtesy of Los Angeles Daily News

Ballet Review

Ballet Visionaries

Los Angeles Ballet

Reviewed by Dany Margolies

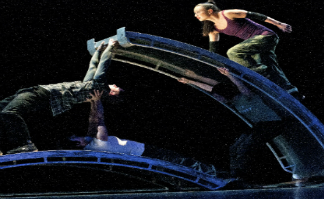

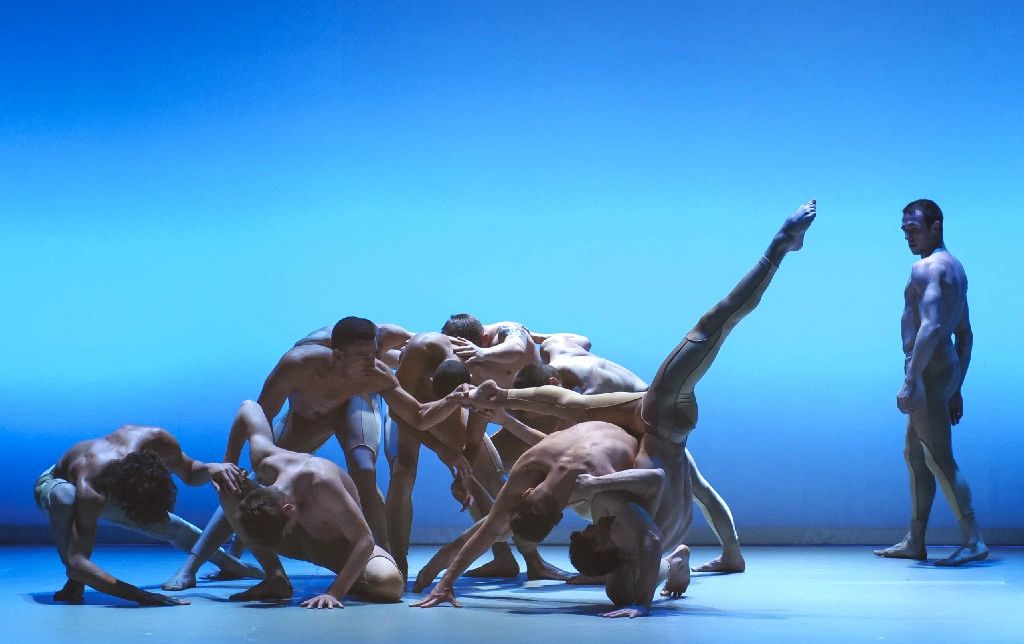

The Los Angeles Ballet in Untouched

Two iconoclastic expatriate Russians, a 19th-century Dane who dug the Italian beat, and a Canadian bending dance in new directions inspired the mixed bill Los Angeles Ballet has titled “Ballet Visionaries,” on local stages this month. But American bravery and willpower made this opening night a thrill to remember.

The evening started not with the traditional precurtain welcome from the company’s co–artistic director Colleen Neary but with a succinct announcement: The roles scheduled to be danced by Allyssa Bross, one of the company’s two principal ballerinas, were being taken on by two other dancers. (Bross reportedly bruised her ribs crashing into a fixture as she came offstage during dress rehearsal the night before opening.)

So, with one day to prepare, two women with technique, intelligence, and courage stepped in. And then, up went the curtain. No excuses, no apologies. None needed. The mixed bill begins with choreography by George Balanchine (1904–1983) to the violin concerto composed by his dear friend Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971). Both men had left their native Russia to nest in New York, changing the course of their art forms. Balanchine choreographed Stravinsky Violin Concerto the year after the composer’s death, reportedly inserting in-jokes he thought Stravinsky would have enjoyed.

He first introduces the ensemble and two lead couples, clad in leotards and tights—considered rehearsal clothes until Balanchine put them onstage. The second movement, danced here by Elizabeth Claire Walker (for Bross) and Dustin True, features a pas de deux of detachment, of ways two dancers could be wary of, escape from and reject each other.

He first introduces the ensemble and two lead couples, clad in leotards and tights—considered rehearsal clothes until Balanchine put them onstage. The second movement, danced here by Elizabeth Claire Walker (for Bross) and Dustin True, features a pas de deux of detachment, of ways two dancers could be wary of, escape from and reject each other.

The third movement, with Julia Cinquemani and Kenta Shimizu, shows a more solicitous couple. Still, the man imprisons and manipulates the woman, pinning her knees together, bending her torso, then taking her forehead back until she cannot see her path. Granted, Walker and True were underrehearsed, but Cinquemani and Shimizu evidenced more thoughtfulness, more purpose, even in this abstract ballet. The finale toys with fundamentals of Russian folk dance but also gives the corps a chance to display its joyful precision.

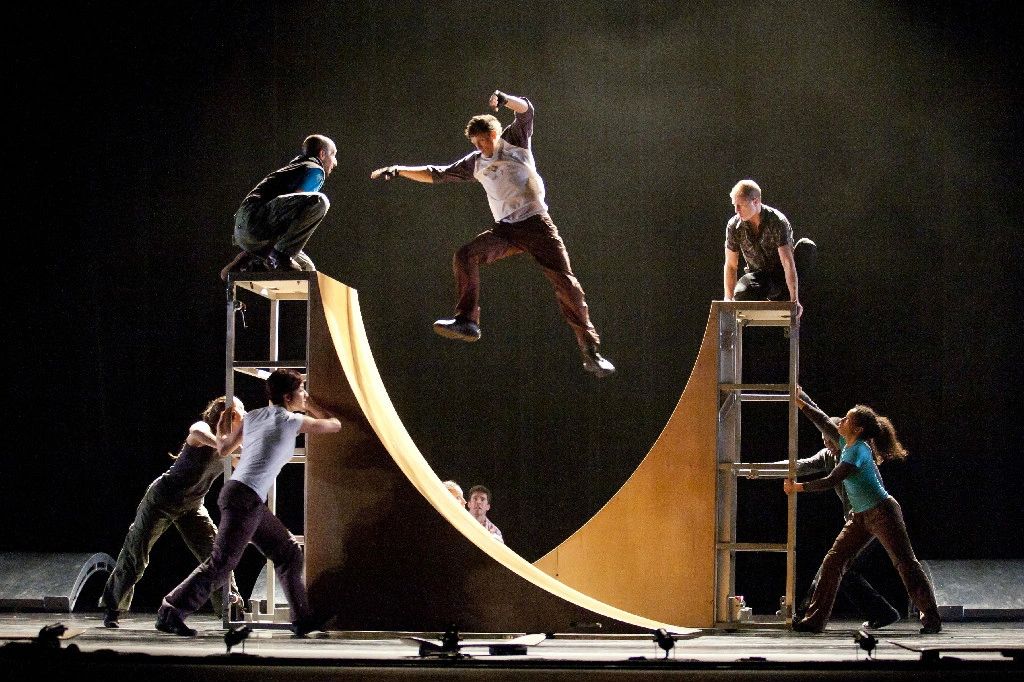

Next, the company performed the 2010 choreography of Canadian Aszure Barton. Titled Untouched, it is even more abstract than the Balanchine. Still, Untouched is endlessly enthralling, moody, and quite beautiful, and probably even more fiendishly difficult than Violin Concerto.

To music by Njo Kong Kie, Curtis Macdonald and Lev Zhurbin, the piece begins with a striking solo by Abby Callahan, puts Shimizu in quirky struts and stage-spanning slides, and displays a flawless foursome—of Bianca Bulle and Tigran Sargsyan, Chelsea Paige Johnston and True—that brings the work to a finale in which all the shimmies, tummy rubs and torqueing walks come to a fascinating conclusion.

To vibrantly end the evening, company co–artistic director Thordal Christensen, trained with the Royal Danish Ballet, stages the quintessentially Danish Pas de Six and Tarantella from Napoli, choreographed by August Bournonville (1805–79) to music by Edvard Helsted and Holger Paulli.

Dustin True, Tigran Sargsyan, Julia Cinquemani, Kate Highstrete, Madeline Houk, Ashley Millar in Napoli

The dancers weren’t the only brave ones here. Neary and Christensen didn’t choose a program designed solely to bring in the masses. These ballets are not famous, they’re not “accessible.” But they need to be seen and kept alive. Plotless and abstract, each piece seems to be about independence and yet collegiality. Each in its own way has an internal beauty. In this celebration of internationality, dancers and directors, whether born here or not, summoned all-American stamina and bravery for an inspirational night of ballet.

Bournonville style consists of perpetual motion—mostly small jumps (called petit allegro in ballet) seasoned with a few big jumps just when one imagines the dancers ought to be collapsing. But in addition to stamina, the dancers here show the refinement the style calls for. Arms are held low or occasionally at shoulder height, offering little help in jumping. Hands are politely relaxed, legs are rarely raised above 45 degrees, ballet is at its most gracious in an era when acrobatics seems to be valued over elegance and effortlessness.

Shimizu again shows his versatility, also creating a character—this one the jealous bridegroom—opposite the dainty Bulle. Madeline Houk, replacing Bross, not only managed the style but also dealt with a long scarf that required coordinating with her daring partner, True.

So, the show went on, thanks to the women who stepped into a breach. They were hoisted by men who had spent weeks rehearsing with Bross’s proportions and momentum. In time to the music, the replacements swiftly clasped hands with and leapt perilously near other dancers. And no one gave off the slightest hint of the impending dangers of a missed connection or a collision. This is professionalism. This is bravery.

The dancers weren’t the only brave ones here. Neary and Christensen didn’t choose a program designed solely to bring in the masses. These ballets are not famous, they’re not “accessible.” But they need to be seen and kept alive. Plotless and abstract, each piece seems to be about independence and yet collegiality. Each in its own way has an internal beauty. In this celebration of internationality, dancers and directors, whether born here or not, summoned all-American stamina and bravery for an inspirational night of ballet.

Middle photo: Kenta Shimizu and Julia Cinquemani in Stravinsky Violin Concerto. Photo © Reed Hutchinson and the Los Angeles Ballet 2016

Ballet Visionaries

Los Angeles Ballet

Reviewed by Dany Margolies

The Los Angeles Ballet in Untouched

Photo © Reed Hutchinson and the Los Angeles Ballet 2016

Two iconoclastic expatriate Russians, a 19th-century Dane who dug the Italian beat, and a Canadian bending dance in new directions inspired the mixed bill Los Angeles Ballet has titled “Ballet Visionaries,” on local stages this month. But American bravery and willpower made this opening night a thrill to remember.

The evening started not with the traditional precurtain welcome from the company’s co–artistic director Colleen Neary but with a succinct announcement: The roles scheduled to be danced by Allyssa Bross, one of the company’s two principal ballerinas, were being taken on by two other dancers. (Bross reportedly bruised her ribs crashing into a fixture as she came offstage during dress rehearsal the night before opening.)

So, with one day to prepare, two women with technique, intelligence, and courage stepped in. And then, up went the curtain. No excuses, no apologies. None needed. The mixed bill begins with choreography by George Balanchine (1904–1983) to the violin concerto composed by his dear friend Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971). Both men had left their native Russia to nest in New York, changing the course of their art forms. Balanchine choreographed Stravinsky Violin Concerto the year after the composer’s death, reportedly inserting in-jokes he thought Stravinsky would have enjoyed.

He first introduces the ensemble and two lead couples, clad in leotards and tights—considered rehearsal clothes until Balanchine put them onstage. The second movement, danced here by Elizabeth Claire Walker (for Bross) and Dustin True, features a pas de deux of detachment, of ways two dancers could be wary of, escape from and reject each other.

He first introduces the ensemble and two lead couples, clad in leotards and tights—considered rehearsal clothes until Balanchine put them onstage. The second movement, danced here by Elizabeth Claire Walker (for Bross) and Dustin True, features a pas de deux of detachment, of ways two dancers could be wary of, escape from and reject each other.The third movement, with Julia Cinquemani and Kenta Shimizu, shows a more solicitous couple. Still, the man imprisons and manipulates the woman, pinning her knees together, bending her torso, then taking her forehead back until she cannot see her path. Granted, Walker and True were underrehearsed, but Cinquemani and Shimizu evidenced more thoughtfulness, more purpose, even in this abstract ballet. The finale toys with fundamentals of Russian folk dance but also gives the corps a chance to display its joyful precision.

Next, the company performed the 2010 choreography of Canadian Aszure Barton. Titled Untouched, it is even more abstract than the Balanchine. Still, Untouched is endlessly enthralling, moody, and quite beautiful, and probably even more fiendishly difficult than Violin Concerto.

To music by Njo Kong Kie, Curtis Macdonald and Lev Zhurbin, the piece begins with a striking solo by Abby Callahan, puts Shimizu in quirky struts and stage-spanning slides, and displays a flawless foursome—of Bianca Bulle and Tigran Sargsyan, Chelsea Paige Johnston and True—that brings the work to a finale in which all the shimmies, tummy rubs and torqueing walks come to a fascinating conclusion.

To vibrantly end the evening, company co–artistic director Thordal Christensen, trained with the Royal Danish Ballet, stages the quintessentially Danish Pas de Six and Tarantella from Napoli, choreographed by August Bournonville (1805–79) to music by Edvard Helsted and Holger Paulli.

Dustin True, Tigran Sargsyan, Julia Cinquemani, Kate Highstrete, Madeline Houk, Ashley Millar in Napoli

Photo © Reed Hutchinson and the Los Angeles Ballet 2016

The dancers weren’t the only brave ones here. Neary and Christensen didn’t choose a program designed solely to bring in the masses. These ballets are not famous, they’re not “accessible.” But they need to be seen and kept alive. Plotless and abstract, each piece seems to be about independence and yet collegiality. Each in its own way has an internal beauty. In this celebration of internationality, dancers and directors, whether born here or not, summoned all-American stamina and bravery for an inspirational night of ballet.

Shimizu again shows his versatility, also creating a character—this one the jealous bridegroom—opposite the dainty Bulle. Madeline Houk, replacing Bross, not only managed the style but also dealt with a long scarf that required coordinating with her daring partner, True.

So, the show went on, thanks to the women who stepped into a breach. They were hoisted by men who had spent weeks rehearsing with Bross’s proportions and momentum. In time to the music, the replacements swiftly clasped hands with and leapt perilously near other dancers. And no one gave off the slightest hint of the impending dangers of a missed connection or a collision. This is professionalism. This is bravery.

The dancers weren’t the only brave ones here. Neary and Christensen didn’t choose a program designed solely to bring in the masses. These ballets are not famous, they’re not “accessible.” But they need to be seen and kept alive. Plotless and abstract, each piece seems to be about independence and yet collegiality. Each in its own way has an internal beauty. In this celebration of internationality, dancers and directors, whether born here or not, summoned all-American stamina and bravery for an inspirational night of ballet.

October 10, 2016

Middle photo: Kenta Shimizu and Julia Cinquemani in Stravinsky Violin Concerto. Photo © Reed Hutchinson and the Los Angeles Ballet 2016

Ballet Review

American Ballet

Theatre’s All-

Ratmansky Program

Dorothy Chandler Pavilion at The Music Center

Reviewed by Dany Margolies

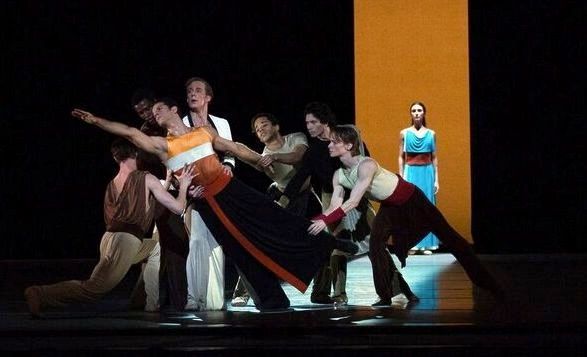

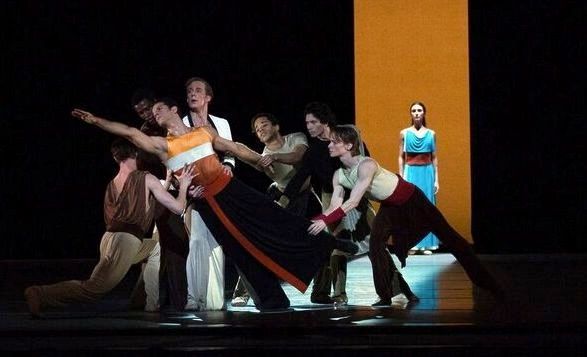

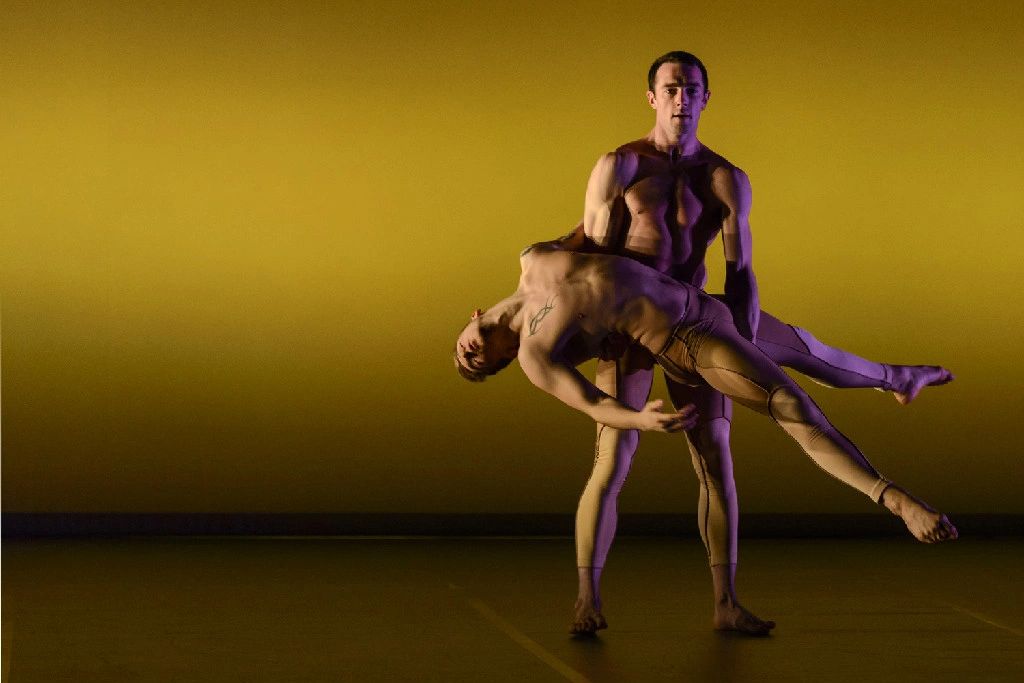

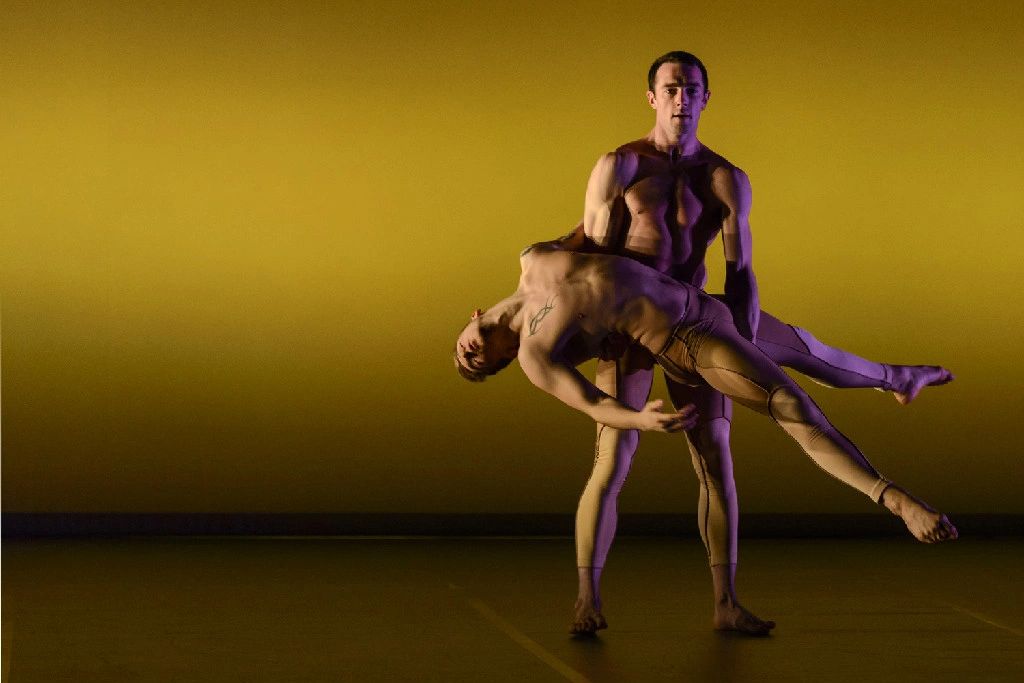

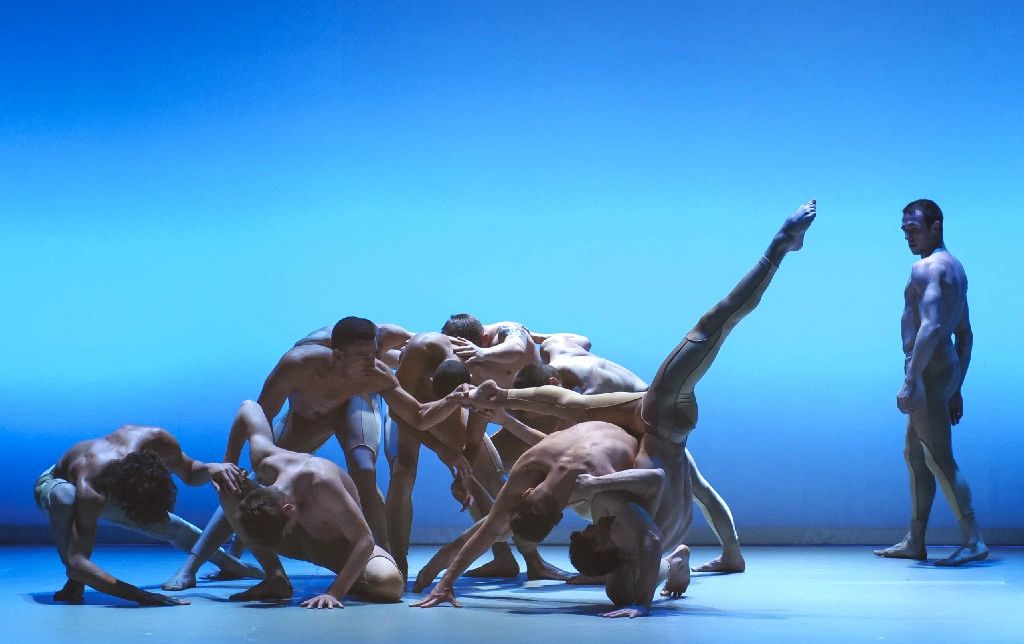

The dancers of Serenade After Plato’s Symposium

Alexei Ratmansky has been called the most gifted choreographer specializing in classical ballet today. The all-Ratmansky program of three of his works, danced by American Ballet Theatre this weekend at The Music Center, seemed to prove otherwise, except in one regard.

Ratmansky is the artist-in-residence with ABT. Formerly, he held the directorship of Moscow’s Bolshoi Ballet, so he comes with expectations of the best of training and talent in his male dancers. And that, perhaps, is how he is “gifted” here.

ABT is stocked with a deep bench of male dancers, including members of the corps de ballet who would be principals in most other companies. But Ratmansky gives them the equivalent of awkward dialogue to speak. His vocabulary is more contemporary ballet than classical, creating movement that seems to have meaning. Then, distractingly, he pops in a recognizable classical-ballet turn, such as a pirouette or tour en l’air. Or, he’ll wedge in a Russian folk-dance step or insert a hand clap.

At the Music Center, ABT’s men were shown to spectacular effect, particularly in the evening’s middle slot, the West Coast premiere of Serenade After Plato’s Symposium, danced to Leonard Bernstein’s violin concerto (conducted crisply by Ormsby Wilkins, featuring tender violin passages by Benjamin Bowman).

Symposium is a conversation, via dance, among seven men in ancient Greece, each getting a dazzling solo. The work starts with one dancer’s statement. Another dancer offers a supporting argument. A counterargument is presented. So far all is clear. The piece then moves into another plane, perhaps revealing man’s emotional states, perhaps revealing the issues he confronts in relating to others. The audience starts to think and feel. And then pretty dance steps start to crop up, culminating in another pirouette into a tour en l’air.

But a series of bourees, steps traditionally done only by women, proves these men have the fluidity and fleetness of ballerinas in addition to the strength and stamina this piece demands.

The program began with Symphony #9, to the music of Dmitri Shostakovich. The men are playful, the women sassy in this mostly aerobic piece. Its style is free and loose-limbed, so the dancers, while not uniform, move in relaxed synchronization. Veronika Part and Alexandre Hammoudi danced the moderato movement, which juxtaposes humor with longing, Part infusing her beautiful technique with dramatic tension. Designer George Tsypin’s backdrop for the Largo movement seems to symbolize war and class, as do the dancers who seem to be waiting and then joining a political movement.

The evening’s last piece was Ratmansky’s overhaul of Firebird.

He has retained the music of Igor Stravinsky and the basics of the

Russian fairy tale about a magical bird and the man she helps in his

search for true love.

The evening’s last piece was Ratmansky’s overhaul of Firebird.

He has retained the music of Igor Stravinsky and the basics of the

Russian fairy tale about a magical bird and the man she helps in his

search for true love.

Other than that, there’s no spotting Mikhail Fokine’s original ballet in here. Indeed, it’s less the dreamy, airy ballet than something that could pass for Seussical the Musical. The Firebird (Isabella Boylston) shakes her tail feathers, literally, for a laugh. The enchanted maidens, held captive by Kaschei the sorcerer (Roman Zhurbin), move as if the evil guy smote them with a bad case of the sillies, at one point doing the Bunny Hop.

Ivan (Hammoudi again) may be in search of love, but he can’t even find the door out of his room. Give Ratmansky this: At the top of the piece, he suggests all might be Ivan’s dream. When Ivan meets The Maiden (Cassandra Trenary), she’s far from ideal. But true love sees through the curse. The dancing is flawless, particularly by Trenary, who gives herself over to her character and dances with comedic and then romantic abandon.

As do the other two works, this Firebird has a happy, Hollywood ending. Yet, somewhat troublingly, each of the “beautiful maidens” is a pale blonde. Fortunately, the beautiful ballerinas dancing the roles are a more representative mix of the races and national heritages that form the “American” in ABT.

Republished with kind permission of Los Angeles Daily News

Photo of Isabella Boylston as the Firebird by Rosalie O’Connor

American Ballet

Theatre’s All-

Ratmansky Program

Dorothy Chandler Pavilion at The Music Center

Reviewed by Dany Margolies

The dancers of Serenade After Plato’s Symposium

Photo by Rosalie O’Connor

Alexei Ratmansky has been called the most gifted choreographer specializing in classical ballet today. The all-Ratmansky program of three of his works, danced by American Ballet Theatre this weekend at The Music Center, seemed to prove otherwise, except in one regard.

Ratmansky is the artist-in-residence with ABT. Formerly, he held the directorship of Moscow’s Bolshoi Ballet, so he comes with expectations of the best of training and talent in his male dancers. And that, perhaps, is how he is “gifted” here.

ABT is stocked with a deep bench of male dancers, including members of the corps de ballet who would be principals in most other companies. But Ratmansky gives them the equivalent of awkward dialogue to speak. His vocabulary is more contemporary ballet than classical, creating movement that seems to have meaning. Then, distractingly, he pops in a recognizable classical-ballet turn, such as a pirouette or tour en l’air. Or, he’ll wedge in a Russian folk-dance step or insert a hand clap.

At the Music Center, ABT’s men were shown to spectacular effect, particularly in the evening’s middle slot, the West Coast premiere of Serenade After Plato’s Symposium, danced to Leonard Bernstein’s violin concerto (conducted crisply by Ormsby Wilkins, featuring tender violin passages by Benjamin Bowman).

Symposium is a conversation, via dance, among seven men in ancient Greece, each getting a dazzling solo. The work starts with one dancer’s statement. Another dancer offers a supporting argument. A counterargument is presented. So far all is clear. The piece then moves into another plane, perhaps revealing man’s emotional states, perhaps revealing the issues he confronts in relating to others. The audience starts to think and feel. And then pretty dance steps start to crop up, culminating in another pirouette into a tour en l’air.

But a series of bourees, steps traditionally done only by women, proves these men have the fluidity and fleetness of ballerinas in addition to the strength and stamina this piece demands.

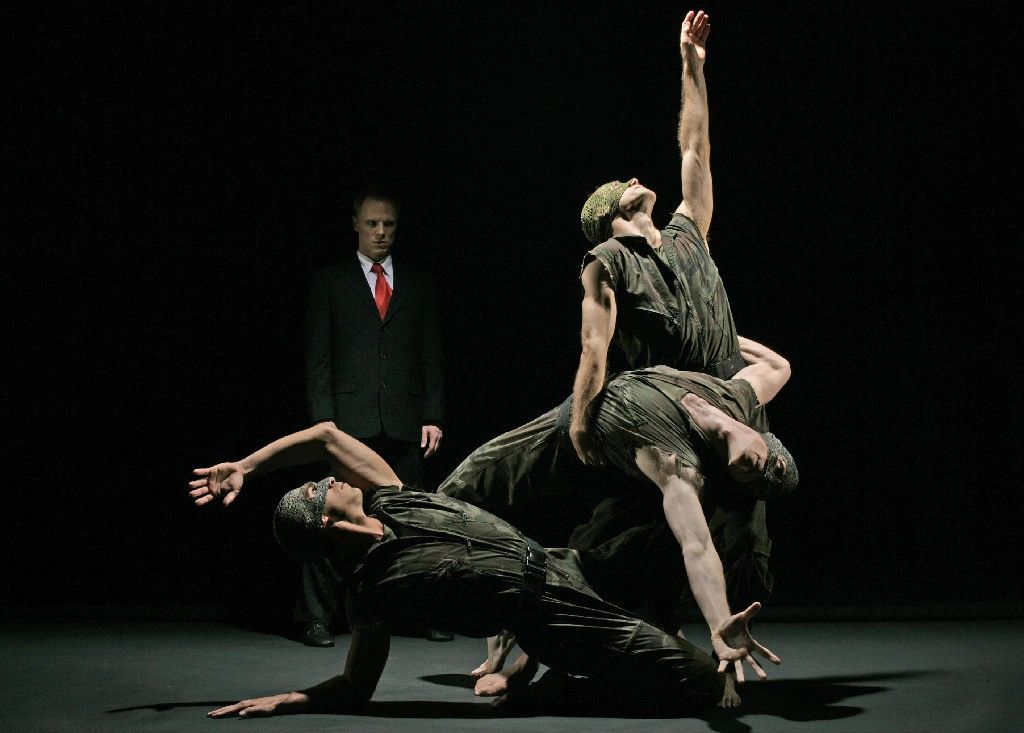

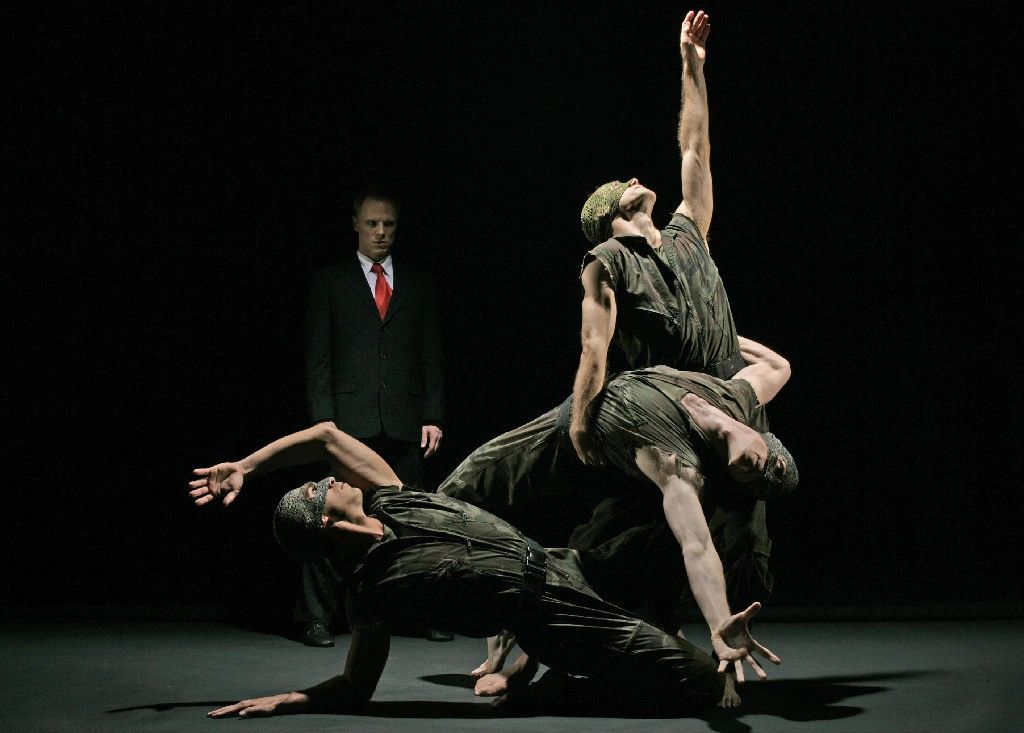

The program began with Symphony #9, to the music of Dmitri Shostakovich. The men are playful, the women sassy in this mostly aerobic piece. Its style is free and loose-limbed, so the dancers, while not uniform, move in relaxed synchronization. Veronika Part and Alexandre Hammoudi danced the moderato movement, which juxtaposes humor with longing, Part infusing her beautiful technique with dramatic tension. Designer George Tsypin’s backdrop for the Largo movement seems to symbolize war and class, as do the dancers who seem to be waiting and then joining a political movement.

The evening’s last piece was Ratmansky’s overhaul of Firebird.

He has retained the music of Igor Stravinsky and the basics of the

Russian fairy tale about a magical bird and the man she helps in his

search for true love.

The evening’s last piece was Ratmansky’s overhaul of Firebird.

He has retained the music of Igor Stravinsky and the basics of the

Russian fairy tale about a magical bird and the man she helps in his

search for true love.Other than that, there’s no spotting Mikhail Fokine’s original ballet in here. Indeed, it’s less the dreamy, airy ballet than something that could pass for Seussical the Musical. The Firebird (Isabella Boylston) shakes her tail feathers, literally, for a laugh. The enchanted maidens, held captive by Kaschei the sorcerer (Roman Zhurbin), move as if the evil guy smote them with a bad case of the sillies, at one point doing the Bunny Hop.

Ivan (Hammoudi again) may be in search of love, but he can’t even find the door out of his room. Give Ratmansky this: At the top of the piece, he suggests all might be Ivan’s dream. When Ivan meets The Maiden (Cassandra Trenary), she’s far from ideal. But true love sees through the curse. The dancing is flawless, particularly by Trenary, who gives herself over to her character and dances with comedic and then romantic abandon.

As do the other two works, this Firebird has a happy, Hollywood ending. Yet, somewhat troublingly, each of the “beautiful maidens” is a pale blonde. Fortunately, the beautiful ballerinas dancing the roles are a more representative mix of the races and national heritages that form the “American” in ABT.

July 11, 2016

Republished with kind permission of Los Angeles Daily News

Photo of Isabella Boylston as the Firebird by Rosalie O’Connor

Ballet Review

Don Quixote

Reviewed by Dany Margolies

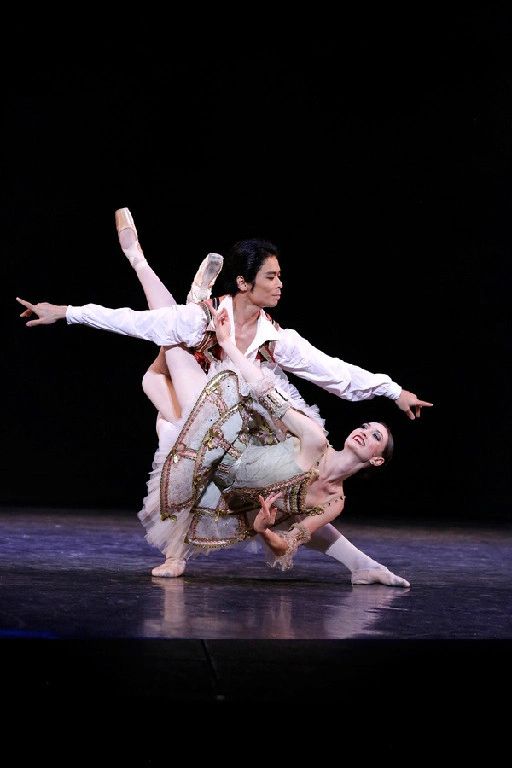

Kenta Shimizu as Basil and Julia Cinquemani as Kitri

The ballet Don Quixote is not known for narrative logic or life lessons. It is, however, known for its nonstop bravura dancing. In Los Angeles Ballet’s version—which opened this weekend at Redondo Beach Performing Arts Center and will appear twice more around the Los Angeles area through March—sparks fly. But they don’t always fly when and where needed.

The 19th-century ballet bears a tangential relationship to the 17th-century Cervantes novel, in which Don Quixote, after too much reading, seems to lose his mind and tries to become one of the knights he reads about.

It’s possible to glean from the muddled storytelling that his main though random quest might be to secure the marriage of the innkeeper’s daughter, Kitri, to the town’s barber, Basil. But what is clear is that this couple can fend for themselves. Only for tradition do we still call this ballet by the chivalric figure’s name. And this being ballet, it uses Don Quixote’s questing to wander into various Spanish settings where pretty much everyone is a fabulous dancer.

The company’s co–artistic directors, Thordal Christensen and Colleen Neary, choreographed here, based on the Russian originals of Marius Petipa and Alexander Gorsky to the vibrant score by Ludwig Minkus with a few dances by Riccardo Drigo (balletomanes will recognize these interpolations from other famous ballets).

The Christensens certainly left in the good bits, including the spectacularly difficult ones. The iconic 32 fouettés (the series of whipping turns done on tiptoe on one leg) that comes at the end of Act 3 merely stamps the seal on two and a half hours of daring balances, twisting leaps, dangerous lifts, and nonstop ballet-type entertainment.

The directors can boast a strong corps de ballet, particularly the men, who dance with the expected explosive bravura, albeit following all the rules of ballet. Some of the women, notably Chelsea Paige Johnston, bring flamenco’s dynamics and the style’s head and shoulder positions into their dances. Also amping up the fire, the powerhouse Allyssa Bross takes on the role of the, ahem, street dancer, Mercedes.

But although the principals—Julia Cinquemani as Kitri and Kenta Shimizu as Basil—are certainly beautifully schooled and technically adept, their portrayals lack that Spanish fire. Instead, from them, we see mostly serene elegance, more suited to the royalty or aristocracy of such ballets as The Sleeping Beauty and Raymonda.

Granted, Cinquemani could have been nervous at the top of the ballet. There’s a lot to carry here, technically and narratively. Her first few series of jumps are an iconic ballet moment: Kitri circles the stage with a split leaps so big that she ought to be able to touch her foot above her head as she arches back.

Cinquemani looked as if her feet were already giving out under her. But with each entrance as the ballet went along, she certainly seemed to gain her confidence and regain her technique. By Act 2, she bounded and sparkled, and she was fresh and raring for the world-famous Act 3 pas de deux. And, yes, she flew through her 32 fouettés.

So, remember Don Quixote? Rather than leaving the knight-errant out of the story completely, he’s brought onstage here and asked to somehow participate in his scenes. Performing the role, Adam Lüders does this by waving his arms airily.

Want to see characterization with specificity and purpose? Take a peek at—or keep your eyes glued on—Zheng Hua Li as he plays Kitri’s repulsive suitor, Gamache. The dancer has obviously made serious study of commedia dell’arte. From Gamache’s prissy first entrance through his deluded astonishment that Kitri could find a better mate than he, Li stays deeply in hilarious character throughout. Another comedic gem, onstage too briefly, is the Don’s wise but weary horse (uncredited).

Not helping the audience settle into any narrative threads, the sets and costumes, designed by Nikolas Georgiadas, are not the best around. The set includes such puzzling elements as square red columns; and too many of the costumes bear too little relationship to the story, in particular the Centurion-style bodices for the wood nymphs.

Yes, wood nymphs. At least Act 2 offers plenty of spectacular dancing by the company’s deep bench—including Bianca Bulle as a floaty Queen of the Dryads, and Dustin True as the head gypsy who leads his band in a traditional Russian-style mazurka. Again, this ballet promises panache, not ethnic accuracy nor storytelling logic. And, to a large extent, it keeps its promise.

Don Quixote

Reviewed by Dany Margolies

Kenta Shimizu as Basil and Julia Cinquemani as Kitri

Photo by Reed Hutchinson

The ballet Don Quixote is not known for narrative logic or life lessons. It is, however, known for its nonstop bravura dancing. In Los Angeles Ballet’s version—which opened this weekend at Redondo Beach Performing Arts Center and will appear twice more around the Los Angeles area through March—sparks fly. But they don’t always fly when and where needed.

The 19th-century ballet bears a tangential relationship to the 17th-century Cervantes novel, in which Don Quixote, after too much reading, seems to lose his mind and tries to become one of the knights he reads about.

It’s possible to glean from the muddled storytelling that his main though random quest might be to secure the marriage of the innkeeper’s daughter, Kitri, to the town’s barber, Basil. But what is clear is that this couple can fend for themselves. Only for tradition do we still call this ballet by the chivalric figure’s name. And this being ballet, it uses Don Quixote’s questing to wander into various Spanish settings where pretty much everyone is a fabulous dancer.

The company’s co–artistic directors, Thordal Christensen and Colleen Neary, choreographed here, based on the Russian originals of Marius Petipa and Alexander Gorsky to the vibrant score by Ludwig Minkus with a few dances by Riccardo Drigo (balletomanes will recognize these interpolations from other famous ballets).

The Christensens certainly left in the good bits, including the spectacularly difficult ones. The iconic 32 fouettés (the series of whipping turns done on tiptoe on one leg) that comes at the end of Act 3 merely stamps the seal on two and a half hours of daring balances, twisting leaps, dangerous lifts, and nonstop ballet-type entertainment.

The directors can boast a strong corps de ballet, particularly the men, who dance with the expected explosive bravura, albeit following all the rules of ballet. Some of the women, notably Chelsea Paige Johnston, bring flamenco’s dynamics and the style’s head and shoulder positions into their dances. Also amping up the fire, the powerhouse Allyssa Bross takes on the role of the, ahem, street dancer, Mercedes.

But although the principals—Julia Cinquemani as Kitri and Kenta Shimizu as Basil—are certainly beautifully schooled and technically adept, their portrayals lack that Spanish fire. Instead, from them, we see mostly serene elegance, more suited to the royalty or aristocracy of such ballets as The Sleeping Beauty and Raymonda.

Granted, Cinquemani could have been nervous at the top of the ballet. There’s a lot to carry here, technically and narratively. Her first few series of jumps are an iconic ballet moment: Kitri circles the stage with a split leaps so big that she ought to be able to touch her foot above her head as she arches back.

Cinquemani looked as if her feet were already giving out under her. But with each entrance as the ballet went along, she certainly seemed to gain her confidence and regain her technique. By Act 2, she bounded and sparkled, and she was fresh and raring for the world-famous Act 3 pas de deux. And, yes, she flew through her 32 fouettés.

So, remember Don Quixote? Rather than leaving the knight-errant out of the story completely, he’s brought onstage here and asked to somehow participate in his scenes. Performing the role, Adam Lüders does this by waving his arms airily.

Want to see characterization with specificity and purpose? Take a peek at—or keep your eyes glued on—Zheng Hua Li as he plays Kitri’s repulsive suitor, Gamache. The dancer has obviously made serious study of commedia dell’arte. From Gamache’s prissy first entrance through his deluded astonishment that Kitri could find a better mate than he, Li stays deeply in hilarious character throughout. Another comedic gem, onstage too briefly, is the Don’s wise but weary horse (uncredited).

Not helping the audience settle into any narrative threads, the sets and costumes, designed by Nikolas Georgiadas, are not the best around. The set includes such puzzling elements as square red columns; and too many of the costumes bear too little relationship to the story, in particular the Centurion-style bodices for the wood nymphs.

Yes, wood nymphs. At least Act 2 offers plenty of spectacular dancing by the company’s deep bench—including Bianca Bulle as a floaty Queen of the Dryads, and Dustin True as the head gypsy who leads his band in a traditional Russian-style mazurka. Again, this ballet promises panache, not ethnic accuracy nor storytelling logic. And, to a large extent, it keeps its promise.

February 22, 2016

Interview

Giving Us the Wilis

Abigail Boyle creates the cruel queen Myrtha in Royal New Zealand Ballet’s ‘Giselle.’

by Dany Margolies

Abigail Boyle and Jacob Chown, with the Royal New Zealand Ballet corps,in Giselle

The 19th century ballet Giselle tells of a young woman whose heart and mind are broken by a young man, Albrecht. He had made Giselle promises of love that he failed to keep. She dies of heartache and madness. Albrecht visits her grave but sees she has become a Wili, an eternally vengeful female spirit. But Giselle’s kindness and gentleness won’t let her punish Albrecht, despite the strictures of Wili sisterhood, presided over by Myrtha, the queen of the Wilis.

At least that’s the way the original ballet, with music by Adolphe Adam and choreography by Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot unfolded. These days, Royal New Zealand Ballet has a reportedly revised new version, choreographed by Johan Kobborg, formerly of the Royal Danish Ballet and the Royal Ballet, and Ethan Stiefel, formerly of American Ballet Theatre.

Giselle is the ballet’s titular lead, but the most interesting role in

it may be that of Myrtha. Abigail Boyle is one of three ballerinas

portraying the cold queen in RNZB’s version. A member of the company

since 2005 and a graduate of the International Ballet Academy in

Christchurch, she admits her training is a mix of Vaganova (Russian) and

Royal Academy of Dance (English) training, to which she has added input

from the American Stiefel.

Giselle is the ballet’s titular lead, but the most interesting role in

it may be that of Myrtha. Abigail Boyle is one of three ballerinas

portraying the cold queen in RNZB’s version. A member of the company

since 2005 and a graduate of the International Ballet Academy in

Christchurch, she admits her training is a mix of Vaganova (Russian) and

Royal Academy of Dance (English) training, to which she has added input

from the American Stiefel.

Boyle doesn’t see Myrtha as only a vicious spirit. “I think she’s somewhat of royalty in her past life, so she knows how to gain and sustain control, which his how she has power,” says Boyle. “It’s in her blood.”

Thus, Boyle plays her as coldly as ballet aficionados would expect, but Boyle says she has created sadness in her, too. She admits she forged the character the way actors do: recalling things in her own past that hurt her, thinking of vengefulness born of the failure to vent at the time.

Boyle admits her demeanor suits stronger roles. In other words, she looks like Myrtha should—commanding, powerful, sturdy—rather than like the frail, ethereal Giselle. And the choreography, she says, helps create Myrtha’s power. As Myrtha forces men to die, “I feel this pulse within me, huge anger. Girl power,” says Boyle.

Not surprisingly, she says the greatest challenge in performing the role is stamina, “having the strength to pump your legs for those big jumps.” Boyle and the two other company members with whom she shares the role—Lucy Balfour and Mayu Tanigaito—may each dance it with their own interpretations, but each roots for the other. “We rev each other up, ‘Come on, girl!’” reports Boyle.

The night before the show, Boyle begins to go through the role in

her head, imagining herself onstage dancing it. On the day of the show,

she’ll take ballet class at 1pm, then mark (easily go through) the

choreography, then eat her dinner, lie down for 20 minutes, and then

ready herself for her appearance, which comes in Act Two.

The night before the show, Boyle begins to go through the role in

her head, imagining herself onstage dancing it. On the day of the show,

she’ll take ballet class at 1pm, then mark (easily go through) the

choreography, then eat her dinner, lie down for 20 minutes, and then

ready herself for her appearance, which comes in Act Two.

When she’s backstage, she says, “I try to disassociate myself with everyone in the dressing room, put myself in a bubble.” On shows in the past, she has listened to Nirvana. For this one, she says she’ll just “tuck myself away and start pulling up Myrtha.”

All this makes coming out of character difficult for her after the performance. “I feel like she’s always around me,” says Boyle. “She does linger.”

So, what’s different and revised about this version? Boyle isn’t revealing it. She says the choreography is true to the original, “but there are tweaks.” And, she reports, there’s a “slight twist” at the end. Are balletomanes in an uproar over this? “I haven’t heard anything bad,” says Boyle. “People find it more riveting and entertaining. I know I do.”

Giving Us the Wilis

Abigail Boyle creates the cruel queen Myrtha in Royal New Zealand Ballet’s ‘Giselle.’

by Dany Margolies

Abigail Boyle and Jacob Chown, with the Royal New Zealand Ballet corps,in Giselle

Photo courtesy RNZB

The 19th century ballet Giselle tells of a young woman whose heart and mind are broken by a young man, Albrecht. He had made Giselle promises of love that he failed to keep. She dies of heartache and madness. Albrecht visits her grave but sees she has become a Wili, an eternally vengeful female spirit. But Giselle’s kindness and gentleness won’t let her punish Albrecht, despite the strictures of Wili sisterhood, presided over by Myrtha, the queen of the Wilis.

At least that’s the way the original ballet, with music by Adolphe Adam and choreography by Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot unfolded. These days, Royal New Zealand Ballet has a reportedly revised new version, choreographed by Johan Kobborg, formerly of the Royal Danish Ballet and the Royal Ballet, and Ethan Stiefel, formerly of American Ballet Theatre.

Giselle is the ballet’s titular lead, but the most interesting role in

it may be that of Myrtha. Abigail Boyle is one of three ballerinas

portraying the cold queen in RNZB’s version. A member of the company

since 2005 and a graduate of the International Ballet Academy in

Christchurch, she admits her training is a mix of Vaganova (Russian) and

Royal Academy of Dance (English) training, to which she has added input

from the American Stiefel.

Giselle is the ballet’s titular lead, but the most interesting role in

it may be that of Myrtha. Abigail Boyle is one of three ballerinas

portraying the cold queen in RNZB’s version. A member of the company

since 2005 and a graduate of the International Ballet Academy in

Christchurch, she admits her training is a mix of Vaganova (Russian) and

Royal Academy of Dance (English) training, to which she has added input

from the American Stiefel.Boyle doesn’t see Myrtha as only a vicious spirit. “I think she’s somewhat of royalty in her past life, so she knows how to gain and sustain control, which his how she has power,” says Boyle. “It’s in her blood.”

Thus, Boyle plays her as coldly as ballet aficionados would expect, but Boyle says she has created sadness in her, too. She admits she forged the character the way actors do: recalling things in her own past that hurt her, thinking of vengefulness born of the failure to vent at the time.

Boyle admits her demeanor suits stronger roles. In other words, she looks like Myrtha should—commanding, powerful, sturdy—rather than like the frail, ethereal Giselle. And the choreography, she says, helps create Myrtha’s power. As Myrtha forces men to die, “I feel this pulse within me, huge anger. Girl power,” says Boyle.

Not surprisingly, she says the greatest challenge in performing the role is stamina, “having the strength to pump your legs for those big jumps.” Boyle and the two other company members with whom she shares the role—Lucy Balfour and Mayu Tanigaito—may each dance it with their own interpretations, but each roots for the other. “We rev each other up, ‘Come on, girl!’” reports Boyle.

The night before the show, Boyle begins to go through the role in

her head, imagining herself onstage dancing it. On the day of the show,

she’ll take ballet class at 1pm, then mark (easily go through) the

choreography, then eat her dinner, lie down for 20 minutes, and then

ready herself for her appearance, which comes in Act Two.

The night before the show, Boyle begins to go through the role in

her head, imagining herself onstage dancing it. On the day of the show,

she’ll take ballet class at 1pm, then mark (easily go through) the

choreography, then eat her dinner, lie down for 20 minutes, and then

ready herself for her appearance, which comes in Act Two.When she’s backstage, she says, “I try to disassociate myself with everyone in the dressing room, put myself in a bubble.” On shows in the past, she has listened to Nirvana. For this one, she says she’ll just “tuck myself away and start pulling up Myrtha.”

All this makes coming out of character difficult for her after the performance. “I feel like she’s always around me,” says Boyle. “She does linger.”

So, what’s different and revised about this version? Boyle isn’t revealing it. She says the choreography is true to the original, “but there are tweaks.” And, she reports, there’s a “slight twist” at the end. Are balletomanes in an uproar over this? “I haven’t heard anything bad,” says Boyle. “People find it more riveting and entertaining. I know I do.”

January 24, 2014

Interview

Dancing for and of the Mind

Mythili Prakash and Aditya Prakash tell ‘Mara’ through Indian classical dance and music.

by Dany Margolies

Mythili Prakash, fourth from left, with dancers of Mara

Mythili Prakash, fourth from left, with dancers of Mara

On a hot morning, a show rehearses in the community room of a church in the South Bay area. Warm-up scales waft from a saxophone. Tennis shoes chirp against the wooden floor as other musicians load in. A neighboring dog provides the counterpoint. Two mothers set up a tailgate party in the parking lot, ready for a long day as their young daughters in rehearsal garb gather in the hall.

Well, there’s universality in the making of art. It sounds like a day

in the life of “Western” musical theater performers, right? But the

medium here is Bharata Natyam—or Bharatanatyam if you prefer—the

classical dance of South India, set to South Indian classical music.

Well, there’s universality in the making of art. It sounds like a day

in the life of “Western” musical theater performers, right? But the

medium here is Bharata Natyam—or Bharatanatyam if you prefer—the

classical dance of South India, set to South Indian classical music.

And in this case, the performers include the choreographer-dancer Mythili Prakash, vocalist Aditya Prakash and the musicians of Aditya Prakash Ensemble, and the dancers of Shakti Dance Company. They’re rehearsing for the world premiere of Mara, a multimedia dance and musical theater production, set for Sept. 21 at the Ford Theatre in Hollywood.

According to the company, “Mara explores the journey of the individual (Jeeva), as she negotiates the dangerous, dazzling maze that is the human mind (Mara). Mara, the demon who infamously attempted to entice Buddha, continues to distract humans from discovering what lies beyond worldly pleasures, the pursuit of true inner freedom. Can Jeeva break free from the chains that bind her to this world?”

The rehearsal begins with Siddhartha, portrayed by a very still dancer, sitting under the Bodhi tree, portrayed by dancers gently manipulating strips of delicate green fabric. The tale of the Buddha begins to unfold, Aditya singing the narration, the dancers working in universal gestures and recognizable activities, even while using the expressive eyes, signature hand positions, and traditional foot stamps of South Indian dance.

Practice (eventually) makes perfect

Aditya and Mythili, brother and sister, are Los Angeles natives. He says most parents

of Indian-heritage children, especially those children born in America,

enroll those children in music or dance classes to keep them in touch

with their roots. His parents, too, tried to make him learn dance. “That

didn’t work out,” he says. So they tried music lessons. He wouldn’t

practice, even with a promised reward of TV. Once the young boy got

through the rigors of the basics, however, his interest grew.

Aditya and Mythili, brother and sister, are Los Angeles natives. He says most parents

of Indian-heritage children, especially those children born in America,

enroll those children in music or dance classes to keep them in touch

with their roots. His parents, too, tried to make him learn dance. “That

didn’t work out,” he says. So they tried music lessons. He wouldn’t

practice, even with a promised reward of TV. Once the young boy got

through the rigors of the basics, however, his interest grew.

Mythili, on the other hand, couldn’t wait to start her dance career. She is the daughter of dancer and teacher Viji Prakash. Mama wouldn’t let the tiny tot join the classes at the dance school she headed. Then she got quite a jolt when the 3-year-old Mythili performed one of the dances for her.

Mythili says learning Bharata Natyam is similar to learning ballet.

“It’s very structured,” she says. “You go through a few years of basics:

technique, Adavus [loosely stated, the steps], the grammatical blocks.

It takes at least a year to learn the whole syllabus. Then you progress

to dances.” In her case, however, because of her early and immediate

immersion, the learning process was a little different.

Mythili says learning Bharata Natyam is similar to learning ballet.

“It’s very structured,” she says. “You go through a few years of basics:

technique, Adavus [loosely stated, the steps], the grammatical blocks.

It takes at least a year to learn the whole syllabus. Then you progress

to dances.” In her case, however, because of her early and immediate

immersion, the learning process was a little different.

While a ballet dancer needs an appropriate body (able to turn out at the hips, for example), with this style, says Mythili, the dancer needs musicality, as the accompaniment is highly complex rhythmically. The dancer must also “involve” herself, feeling the storytelling. “And transforming yourself, but we say that comes later,” she says. Also vital to the form are the facial expressions, the intricate use of the hands, the head-shaking.

But, she adds, “It’s hard to dance together, because everyone is so different. It’s not, ‘Here you raise your eyebrow.’ You breathe your own into it, naturally. As you mature, your expression matures; you develop the interpretation even more.”

Travails and travels

Not everyone in the family is a performer, nor did everyone immediately appreciate the path the siblings took. The siblings’ father is a businessman. However, he helped his wife start her dance school. “That’s what fueled my and my sister’s love for the arts,” says Aditya. Over the summers, Viji would bring musicians from India for her dance productions. Her son recalls, “When they were here, I was soaked in the atmosphere of Indian classical music. I learned with these musicians from India. Then I started wanting to have more regular classes. There are a lot of Indian classical teachers here. I went to classes in Cerritos. My next step, I wanted to go to South India.”

So, Aditya traveled Chennai, India, which he terms the hub of South Indian classical music. “I learned with venerated gurus,” he says. “The thing with Indian classical music, the whole teacher-student relationship is vital to that tradition. You need one-on-one classes with a guru. Once I went to India, my focus turned away from being an engineer or doctor, like my grandma wanted me to be.”

Now, he says, his grandma is all for his artistic path. And fortunately his parents pushed him through those early stages of reluctant learning, until he began to listen to concerts and intently practice on his own. He began studying at age 8 and gave his first solo vocal concert—“They’re usually two to three hours,” he reports—at age 13.

At ages 16 through 19, he began touring with Ravi Shankar. “He’s the one who inspired me to do music full time,” Aditya says. “I was so lucky, at 16 to be able to tour, travel, learn, perform, perform at Carnegie Hall, the Hollywood Bowl, when I was 17. This is what Indian classical music can do: It can reach American audiences and touch people, even though they don’t know the art form. It can create emotion. That’s what Indian music is, it’s emotion, bringing out something you won’t feel in daily life.”

So he doesn’t need to study anymore, right? “You’re always learning, scales, practicing, warming up,” he says, so the process of studying never stops.

Mothering and mentoring

Mythili, too, still studies. Her mother is her main teacher, though the daughter says it’s more of a mentorship at this point. Mythili also has a mentor in India: Malavika Sarukkai. “My classes with her are showing my choreography, and we comb through it,” says Mythili. Sarukkai urges Mythili to clarify details, to bring mindfulness to her choreography.

For example, Mythili created a dance about the wife of Buddha and her

journey when Buddha leaves her. Mythili choreographed a segment in

which the wife was painting a portrait. So Mythili and her mentor worked

in detail, exploring how to show thoughts and emotions with the back of

the body, how to show retreat, betrayal, disappointment.

For example, Mythili created a dance about the wife of Buddha and her

journey when Buddha leaves her. Mythili choreographed a segment in

which the wife was painting a portrait. So Mythili and her mentor worked

in detail, exploring how to show thoughts and emotions with the back of

the body, how to show retreat, betrayal, disappointment.

Mythili recalls the two discussing, “How do my feet feel, what is the speed with which I walk? I carry material, which I throw on the picture. With what force? If I’m miming material, she’ll ask what color the material is.”

Aditya, too, is still on the never-ending path to improving his artistry. “Indian classical music is based on melodic scales called ragas—I could talk for hours, but that’s the skeletal definition,” he says. “Each raga has its own identity, its own emotion. The work, the constant practicing, is to bring those out without changing its structure, having the freedom to bring out one’s own creativity.”

With Western vocal music, a voice coach is usually part of the initial lessons. With Indian classical, says Aditya, “unfortunately” nobody guided his vocal technique early on, so he developed vocal nodules when he was 14. He had a “frustrating” time of it and was forced to stop singing—indeed, to stop talking for three to four months. In addition, the breaking of his voice in adolescence ushered in a tough time. Finally, he said, “I started to figure out my voice, meeting with vocal coaches in India. I began to use Western voice techniques. Now it’s about discovering your own voice and discovering the secrets behind it. I’m always constantly doing it.”

Ragas and riffs

What if he weren’t immersed in Indian music? He admits to being attracted to flamenco music, Qawwali from Pakistan, and jazz. Really, jazz? During his days studying ethnomusicology at UCLA, he lived with three jazz musicians, who would jam. “I’d be there but not participating,” Aditya recalls. “During one of the sessions, I got prodded to sing. We improvised, and something came out of it that was amazing.”

The group stayed together, performing as the Aditya Prakash Ensemble, starting as a vocalist plus jazz trio of piano, bass, and drums. At the premiere of Mara, the ensemble will also include horn, guitar, Indian classical violin, Latin percussion, and Indian percussion. What do the knowledgeable audiences hear in this music? Aditya says they hear the technicalities of the system, for example whether he’s singing the proper phrases. “You have to be on top of your game, you have to focus on getting the techniques of the raga right,” he explains. “There are certain phrases people want to hear. For me, when I perform for an audience, I try to keep those technicalities in place, but I feel I can let go and focus on emoting. Focusing on technique can make the music dry and heady. It’s about finding balance between the heady style and going from the heart.”

Mara involves much improvising, but, he points out, the production houses 35 dancers and 15 musicians. And, he says, “The goal is to create that world of Mara, so not just music for music’s sake. Every line has a purpose to it. It’s to go with the dance, go with the theme of the show.”

And so, this weekend, the beauty and intricacies of Mara—the character from folklore and the human mind—will be revealed by the once-reluctant music scholar and the once-tiny dance prodigy.

Mythili Prakash portrait for Mara, photo by Roshni Badlani & Kamala Venkatesh

Aditya Prakash, from Vimeo by Alex Rapine

Mythili Prakash, photo by D. Krishnan, courtesy of The Hindu

Mythili Prakash

Aditya Prakesh, fourth from right, and ensemble

Dancing for and of the Mind

Mythili Prakash and Aditya Prakash tell ‘Mara’ through Indian classical dance and music.

by Dany Margolies

Mythili Prakash, fourth from left, with dancers of Mara

Mythili Prakash, fourth from left, with dancers of MaraOn a hot morning, a show rehearses in the community room of a church in the South Bay area. Warm-up scales waft from a saxophone. Tennis shoes chirp against the wooden floor as other musicians load in. A neighboring dog provides the counterpoint. Two mothers set up a tailgate party in the parking lot, ready for a long day as their young daughters in rehearsal garb gather in the hall.

Well, there’s universality in the making of art. It sounds like a day

in the life of “Western” musical theater performers, right? But the

medium here is Bharata Natyam—or Bharatanatyam if you prefer—the

classical dance of South India, set to South Indian classical music.

Well, there’s universality in the making of art. It sounds like a day

in the life of “Western” musical theater performers, right? But the

medium here is Bharata Natyam—or Bharatanatyam if you prefer—the

classical dance of South India, set to South Indian classical music.And in this case, the performers include the choreographer-dancer Mythili Prakash, vocalist Aditya Prakash and the musicians of Aditya Prakash Ensemble, and the dancers of Shakti Dance Company. They’re rehearsing for the world premiere of Mara, a multimedia dance and musical theater production, set for Sept. 21 at the Ford Theatre in Hollywood.

According to the company, “Mara explores the journey of the individual (Jeeva), as she negotiates the dangerous, dazzling maze that is the human mind (Mara). Mara, the demon who infamously attempted to entice Buddha, continues to distract humans from discovering what lies beyond worldly pleasures, the pursuit of true inner freedom. Can Jeeva break free from the chains that bind her to this world?”

The rehearsal begins with Siddhartha, portrayed by a very still dancer, sitting under the Bodhi tree, portrayed by dancers gently manipulating strips of delicate green fabric. The tale of the Buddha begins to unfold, Aditya singing the narration, the dancers working in universal gestures and recognizable activities, even while using the expressive eyes, signature hand positions, and traditional foot stamps of South Indian dance.

Practice (eventually) makes perfect

Aditya and Mythili, brother and sister, are Los Angeles natives. He says most parents

of Indian-heritage children, especially those children born in America,

enroll those children in music or dance classes to keep them in touch

with their roots. His parents, too, tried to make him learn dance. “That

didn’t work out,” he says. So they tried music lessons. He wouldn’t

practice, even with a promised reward of TV. Once the young boy got

through the rigors of the basics, however, his interest grew.

Aditya and Mythili, brother and sister, are Los Angeles natives. He says most parents

of Indian-heritage children, especially those children born in America,

enroll those children in music or dance classes to keep them in touch

with their roots. His parents, too, tried to make him learn dance. “That

didn’t work out,” he says. So they tried music lessons. He wouldn’t

practice, even with a promised reward of TV. Once the young boy got

through the rigors of the basics, however, his interest grew.Mythili, on the other hand, couldn’t wait to start her dance career. She is the daughter of dancer and teacher Viji Prakash. Mama wouldn’t let the tiny tot join the classes at the dance school she headed. Then she got quite a jolt when the 3-year-old Mythili performed one of the dances for her.

Mythili says learning Bharata Natyam is similar to learning ballet.

“It’s very structured,” she says. “You go through a few years of basics:

technique, Adavus [loosely stated, the steps], the grammatical blocks.

It takes at least a year to learn the whole syllabus. Then you progress

to dances.” In her case, however, because of her early and immediate

immersion, the learning process was a little different.

Mythili says learning Bharata Natyam is similar to learning ballet.

“It’s very structured,” she says. “You go through a few years of basics:

technique, Adavus [loosely stated, the steps], the grammatical blocks.

It takes at least a year to learn the whole syllabus. Then you progress

to dances.” In her case, however, because of her early and immediate

immersion, the learning process was a little different.While a ballet dancer needs an appropriate body (able to turn out at the hips, for example), with this style, says Mythili, the dancer needs musicality, as the accompaniment is highly complex rhythmically. The dancer must also “involve” herself, feeling the storytelling. “And transforming yourself, but we say that comes later,” she says. Also vital to the form are the facial expressions, the intricate use of the hands, the head-shaking.

But, she adds, “It’s hard to dance together, because everyone is so different. It’s not, ‘Here you raise your eyebrow.’ You breathe your own into it, naturally. As you mature, your expression matures; you develop the interpretation even more.”

Travails and travels

Not everyone in the family is a performer, nor did everyone immediately appreciate the path the siblings took. The siblings’ father is a businessman. However, he helped his wife start her dance school. “That’s what fueled my and my sister’s love for the arts,” says Aditya. Over the summers, Viji would bring musicians from India for her dance productions. Her son recalls, “When they were here, I was soaked in the atmosphere of Indian classical music. I learned with these musicians from India. Then I started wanting to have more regular classes. There are a lot of Indian classical teachers here. I went to classes in Cerritos. My next step, I wanted to go to South India.”

So, Aditya traveled Chennai, India, which he terms the hub of South Indian classical music. “I learned with venerated gurus,” he says. “The thing with Indian classical music, the whole teacher-student relationship is vital to that tradition. You need one-on-one classes with a guru. Once I went to India, my focus turned away from being an engineer or doctor, like my grandma wanted me to be.”

Now, he says, his grandma is all for his artistic path. And fortunately his parents pushed him through those early stages of reluctant learning, until he began to listen to concerts and intently practice on his own. He began studying at age 8 and gave his first solo vocal concert—“They’re usually two to three hours,” he reports—at age 13.

At ages 16 through 19, he began touring with Ravi Shankar. “He’s the one who inspired me to do music full time,” Aditya says. “I was so lucky, at 16 to be able to tour, travel, learn, perform, perform at Carnegie Hall, the Hollywood Bowl, when I was 17. This is what Indian classical music can do: It can reach American audiences and touch people, even though they don’t know the art form. It can create emotion. That’s what Indian music is, it’s emotion, bringing out something you won’t feel in daily life.”

So he doesn’t need to study anymore, right? “You’re always learning, scales, practicing, warming up,” he says, so the process of studying never stops.

Mothering and mentoring

Mythili, too, still studies. Her mother is her main teacher, though the daughter says it’s more of a mentorship at this point. Mythili also has a mentor in India: Malavika Sarukkai. “My classes with her are showing my choreography, and we comb through it,” says Mythili. Sarukkai urges Mythili to clarify details, to bring mindfulness to her choreography.

For example, Mythili created a dance about the wife of Buddha and her

journey when Buddha leaves her. Mythili choreographed a segment in

which the wife was painting a portrait. So Mythili and her mentor worked

in detail, exploring how to show thoughts and emotions with the back of

the body, how to show retreat, betrayal, disappointment.

For example, Mythili created a dance about the wife of Buddha and her

journey when Buddha leaves her. Mythili choreographed a segment in

which the wife was painting a portrait. So Mythili and her mentor worked

in detail, exploring how to show thoughts and emotions with the back of

the body, how to show retreat, betrayal, disappointment.Mythili recalls the two discussing, “How do my feet feel, what is the speed with which I walk? I carry material, which I throw on the picture. With what force? If I’m miming material, she’ll ask what color the material is.”

Aditya, too, is still on the never-ending path to improving his artistry. “Indian classical music is based on melodic scales called ragas—I could talk for hours, but that’s the skeletal definition,” he says. “Each raga has its own identity, its own emotion. The work, the constant practicing, is to bring those out without changing its structure, having the freedom to bring out one’s own creativity.”

With Western vocal music, a voice coach is usually part of the initial lessons. With Indian classical, says Aditya, “unfortunately” nobody guided his vocal technique early on, so he developed vocal nodules when he was 14. He had a “frustrating” time of it and was forced to stop singing—indeed, to stop talking for three to four months. In addition, the breaking of his voice in adolescence ushered in a tough time. Finally, he said, “I started to figure out my voice, meeting with vocal coaches in India. I began to use Western voice techniques. Now it’s about discovering your own voice and discovering the secrets behind it. I’m always constantly doing it.”

Ragas and riffs

What if he weren’t immersed in Indian music? He admits to being attracted to flamenco music, Qawwali from Pakistan, and jazz. Really, jazz? During his days studying ethnomusicology at UCLA, he lived with three jazz musicians, who would jam. “I’d be there but not participating,” Aditya recalls. “During one of the sessions, I got prodded to sing. We improvised, and something came out of it that was amazing.”

The group stayed together, performing as the Aditya Prakash Ensemble, starting as a vocalist plus jazz trio of piano, bass, and drums. At the premiere of Mara, the ensemble will also include horn, guitar, Indian classical violin, Latin percussion, and Indian percussion. What do the knowledgeable audiences hear in this music? Aditya says they hear the technicalities of the system, for example whether he’s singing the proper phrases. “You have to be on top of your game, you have to focus on getting the techniques of the raga right,” he explains. “There are certain phrases people want to hear. For me, when I perform for an audience, I try to keep those technicalities in place, but I feel I can let go and focus on emoting. Focusing on technique can make the music dry and heady. It’s about finding balance between the heady style and going from the heart.”

Mara involves much improvising, but, he points out, the production houses 35 dancers and 15 musicians. And, he says, “The goal is to create that world of Mara, so not just music for music’s sake. Every line has a purpose to it. It’s to go with the dance, go with the theme of the show.”

And so, this weekend, the beauty and intricacies of Mara—the character from folklore and the human mind—will be revealed by the once-reluctant music scholar and the once-tiny dance prodigy.

September 19, 2013

Mythili Prakash portrait for Mara, photo by Roshni Badlani & Kamala Venkatesh

Aditya Prakash, from Vimeo by Alex Rapine

Mythili Prakash, photo by D. Krishnan, courtesy of The Hindu

Mythili Prakash

Aditya Prakesh, fourth from right, and ensemble

Interview

Corps Values

How ABT ballerina Courtney Lavine has gone from strength to strength.